November 8, 2024–February 9, 2025

If you had never encountered Hans Haacke’s work before, then you might think, upon entering the first room of this exhibition: “Oh nice, look! How pretty and interesting. There are his op art-influenced canvases of the early 1960s, and the physical and organic systems (balloons floating, plants growing) of later in the decade.” In the next space, you might think: “Holy moly! Something must have happened around 1969/70, that guy really had a moment of political awakening—look how fiercely he’s attacking the powerful in the art world.” At which point a Haacke expert might pop up and tell you that of course there is a peculiar, logically imperative connection between those earlier experiments in form, system, and process and the later work that would become the paradigmatic form, system, and process of institutional critique. This expert would have a point. But the desire to always explain that connection as a logically inevitable and linear one is also a bit suspicious and needs to be probed—for which this retrospective (which travels to Belvedere, Vienna) is a welcome occasion.

The above thought experiment would not happen in actuality—before stepping foot in the first room, you have already encountered two later works—and so the show, curated by the Schirn’s Ingrid Pfeiffer, mimics the impossibility for anyone even vaguely aware of Haacke’s practice of seeing the early work without having in mind what is to come. In the rotunda at the museum entrance is the bronze cast of a skeletal horse. Originally conceived for the Fourth Plinth in London’s Trafalgar Square, it refers to the reason that plinth remained empty in the first place: an equestrian statue of King William IV, commissioned after his death in 1837, never came into being due to a lack of funding. Larger than life, Haacke’s cast is inevitably reminiscent of a dinosaur fossil. What’s more, an electronic ticker ribbon around its left front thigh gives a live display of the current prices at the Frankfurt Stock Exchange. Gift Horse (2014) adds up to a pretty good joke: if there’s not enough money to realize the gigantic equestrian statue celebrating a fossil, ossified institution, let’s do a skeletal version and present it with a gift ribbon that hints at where the money has gone instead.

On the stairs up to the first floor, a photograph serves as a placeholder for one of Haacke’s best-known works, his treatment of the German Pavilion in Venice in 1993. With the building’s travertine floor—inaugurated by Hitler himself—chopped up into broken tiles, making visitors stumble around on a cracking sea of ice, and with “Germania” emblazoned on the wall behind, Haacke forever changed the way not only the German, but all national pavilions would be approached. He made it impossible, from that point on, to not think of a country’s history in regard to the perception of its pavilion: as artist and audience alike, you can decide to ignore that history, but if you do, it might come back to bite you.

Nothing really would have indicated in the early work that Haacke would one day produce such monumental takedowns of monumentality. On the modestly sized oil on canvas Ce n’est pas la voie lactée (This Is Not The Milky Way, 1960), densely placed blue dots form a spatial, cosmic continuum. The very choice of color may be a nod to Yves Klein, the title to René Magritte’s La Trahison des Images (The Treachery of Images, 1929). But it was the friendship with Otto Piene, grand seigneur of the Zero movement, which had the most immediate impact on Haacke. This was not only because of works such as Piene’s Pure Energy (1958), a grid of yellow dots filling the picture plane, but also because in 1964 Piene moved to the US to live and teach (at the University of Pennsylvania, and later at MIT), as did Haacke three years later (Cooper Union).

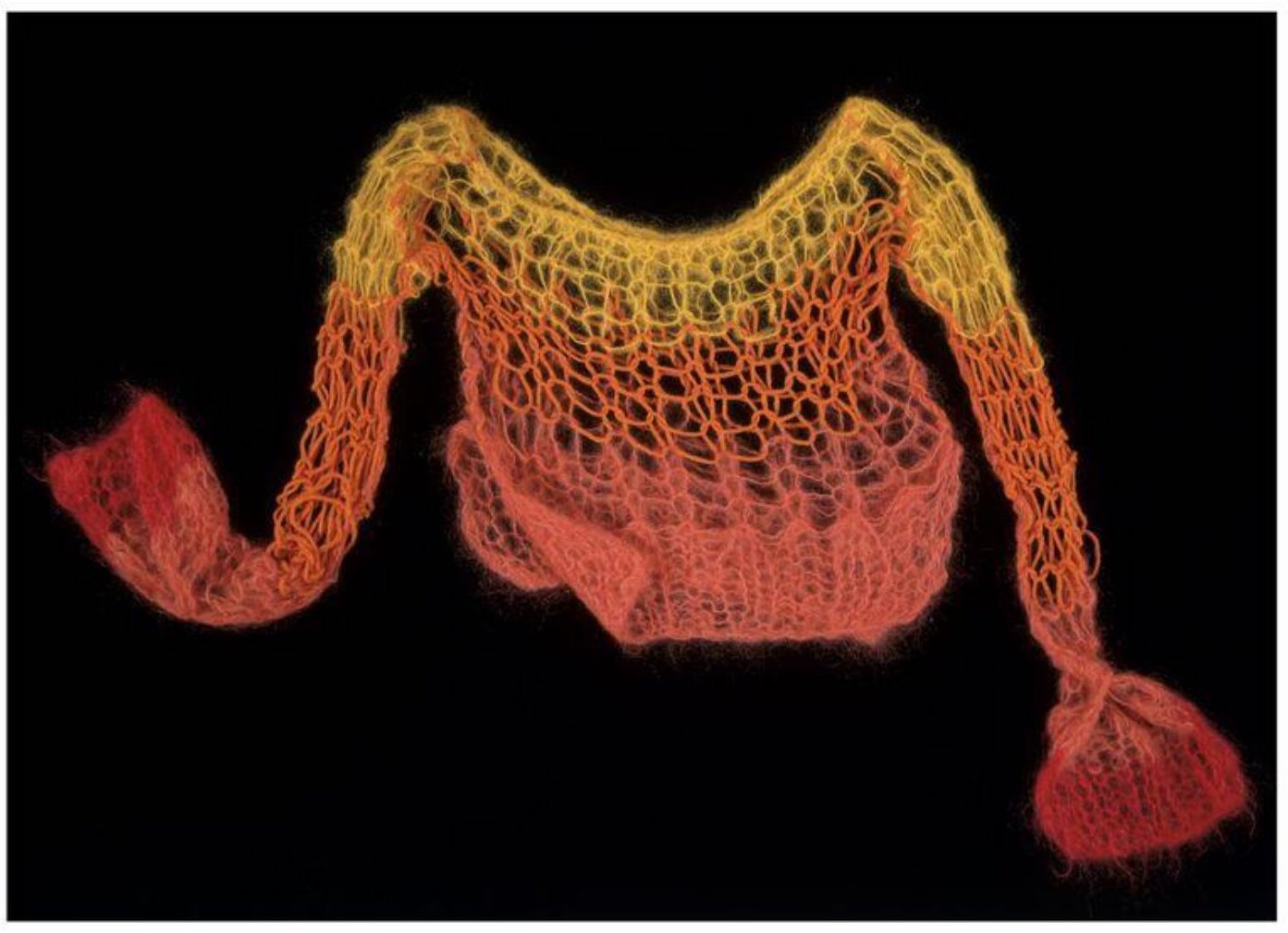

Grids, dots, energy, and US 1960s (post-)minimalist discourse – with Haacke, these factors congealed into elegantly stripped-down processual setups, distributed here across the brightly daylit first space in the exhibition: a piece of chiffon floating in mid-air (Blue Sail, 1964–65), a free-standing pole of ice-covered steel (Ice Stick, 1966), a Plexi box with water inside (Large Condensation Cube, 1963–67), a white room with light bulbs going on and off according to visitor movement (Photo-Electric Viewer-Controlled Coordinate System, 1968), a heap of grass-covered earth (Grass Grows, 1969), or a photograph of seagulls fighting over bread fed to them by the artist (Life Airborne System, 1968). “A ‘sculpture’ that physically reacts to its environment is no longer to be regarded as an object,” Haacke wrote in 1968, quoted by curator Jack Burnham in the programmatically titled Artforum essay “Systems Esthetics” that same year.1

It’s ironic that Burnham based his notion of systems aesthetics—if sideways, and coquettishly so—on military systems analysis, a discipline established during the Cold War of the fifties in anticipation of full-scale warfare. In terms of corresponding to Haacke’s work, more fitting seems the line that leads from Humberto Maturana to Niklas Luhmann (i.e. from biological to social autopoietic systems); or Helmuth Plessner’s notion of “excentric positionality,” meaning humans reflecting on their own systems of regulation. From around 1969/70, it’s as if Haacke started to create model cases of such excentric positionality. As one enters the following parcours, now without daylight, News (1969) is a telex machine churning out an endless paper trail of local news forming a tangled heap on the floor (on the day I visited, headlines included the renovation of a local company’s headquarters and Eintracht Frankfurt soccer club’s championship prospects).

MoMA Poll (1970), famously, caused a stir: as part of the “Information” group exhibition at the museum, visitors were asked to cast a vote in one of two see-through ballot boxes, on whether then-governor Nelson Rockefeller’s position on Nixon’s Indochina policy would be reason enough not to vote for him in upcoming elections. More than two thirds of those who participated affirmed the question. Incidentally, Rockefeller was a trustee of the museum, and his brother David chairman of its board. The latter tried to get the curator John Hightower to remove the piece, but he stood his ground—and was eventually fired.

Instead of avoiding potential conflicts after this rough encounter, in 1971 Haacke kicked into high gear for his solo show at the Guggenheim. Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971, made that year, is a groundbreaking work not so much because it again provoked censorship (the director demanding the removal of the piece) and cancellation (of the show, after Haacke insisting on its inclusion, and the firing of the curator) but because its political thrust came from within artistic exploration itself rather than being grafted onto it. It built not so much on subversive parody or polemical agitation but on meticulous research and a no-nonsense, forensic presentation of the findings. And Haacke resisted the temptation to include explicit instructions on how to interpret them. Detailed diagrams culled from public records and an indexical photo series of run-down apartment buildings paired with further facts (exact location, history of ownership, assessed value, etc.) reveal nepotistic asset structures around one of New York City’s biggest slumlord companies. And that was enough to effectively make Haacke, for decades to come, persona non grata amongst most career-oriented curators.

That in the long-run persistence pays off is easier said than done. Instead of using Europe as a kind of resort, after repeatedly having ruffled feathers in the US, Haacke focused even more specifically on museum donors and collectors. Manet-PROJEKT ’74 (1974), conceived in response to a group show invitation at the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum in Haacke’s native Cologne, is a pioneering master piece of art-as-investigation and the critical discourse around provenance. Its starting point is the museum’s own Une botte d’asperges (A Bundle of Asparagus, 1880) by Édouard Manet. Wall panels provide key information about the social and economic background of the still life’s previous and present owners, from Charles Ephrussi (who bought the work directly from the artist in the year of its making) to the Wallraf-Richartz Museum, via mostly dealers, painters, and relatives, one of whom brought the painting to New York when she fled the Nazis. The driving force of its most recent acquisition was Hermann J. Abs, chair of the museum’s board.

As Haacke points out, Abs was also on the managing board of Deutsche Bank and the advisory board of Reichsbank during the Nazi period, after which he made a smooth transition to life in postwar West Germany where he continued to work in similar positions. Haacke also lists all the foundations and companies that had contributed to the Manet purchase. It’s a veritable who’s who of German economic power, from steel company Thyssen to department store magnate Horten. It becomes glaringly apparent, without Haacke having to spell it out, that all of the previous owners had been Jewish, and that the current ones were part of a network of profiteers of the expropriation of Jewish property—not least Abs himself. Needless to say, the museum refused to exhibit the work; Cologne’s Galerie Paul Maenz exhibited it instead (yes, there are dealers who dare).

A substantial part of Haacke’s work could be described with the adage “he told you so, ages ago,” and this becomes especially apparent with Buhrlesque (1985). It’s a mock church altar, complete with ammunition-belt patterns decorating the binding of its cloth cover, erected to Dietrich Bührle. Bührle was both a Swiss weapons dealer who collaborated with Nazi Germany and Apartheid South Africa and also a major collector of French impressionism. When in 2021 the Kunsthaus Zürich opened its new building with a presentation of the Bührle collection, Miriam Cahn, the Jewish-Swiss artist, withdrew her works from the museum. This was the starting signal for a major scandal, in which the main issue was that the institution had made little effort to make the problematic origin of the collection transparent, much less independently clarify the provenance of a large proportion of the works. It wasn’t until July 2024 that an expert report prepared by historian Raphael Gross established that no fewer than 62 of 205 works on permanent loan to the Kunsthaus Zürich had previously been owned by Jews during the period of Nazi persecution from 1933 to ’45. It’s as if, this time, a collective of artists, historians, journalists and the general public had to do what Haacke had done on his own.

It’s not like there are no influential people—in art and politics—supporting the critical work Haacke has done. In fact, it’s hard to overstate his influence. His seminal proposal of a permanent work for the German parliament, the documentation of which dominates the last section of the exhibition parcours, would have never gotten off the ground without such backing. But it is an increasingly rare form of cross-party support that is only occasionally capable of winning a majority, as it did in the Bundestag in 2000, when the realization of the work was eventually approved by a margin of three. The exhibition includes video documentation of the parliamentary debate before that vote. I got goosebumps when one of the MPs, Ulrich Heinrich from the FDP, passionately defended Haacke’s concept.

The title Der Bevölkerung (To The Population, 2000) comments on the motto emblazoned on the west-portal of the Reichstag parliament building, “Dem Deutschen Volke” (To the German People); the alteration obviously asserts that a real democracy is not only for autochthone citizens in the country but also for those who migrated there, not least in Germany where the idea of the Volkskörper, the national body, was central to Nazi ideology. The concept proposed that in an inner courtyard, “Der Bevölkerung” would be written horizontally on the ground in similar fractured lettering to that on the portal, surrounded by overgrown earth from the constituencies of all the MPs.

Heinrich countered conservative resentment against the idea of an artwork that questioned the hierarchy of “proper” Germans and immigrants, not only by referring to the principle of artistic freedom and tolerance, but also by reminding the members of the House that, under the Nazis, many of the MPs not only lost their mandate and their citizenship, but were harassed, imprisoned, tortured, driven to emigration or suicide, or even murdered. I got goosebumps not only because Heinrich put forth the most chilling and conclusive argument for the piece, but also that he was from the FDP, a party that used to have a civic-liberal wing of which he was a representative, and which today has dramatically shifted towards right-wing libertarianism. Would Haacke’s proposal still get a majority today? I doubt it.

His work over more than six decades could be seen as a kind of unfolding: earlier questions of aesthetic conceptualization, which are implicitly political, at some point—and at a time of protest against the Vietnam War—flipped into questions of political investigation, which are implicitly aesthetic-conceptual. That description of a linear development, in an almost schematic historical-dialectical sense, may seem dubious because it presupposes what it finds. But, vice versa, to accuse that assumption of having retroactively put into the earlier work something that it never contained also feels wrong, because that would mean to indeed ignore the inherent political aspect of that earlier 1960s work.

Rather, Haacke’s oeuvre in toto is an exceptionally consequential reflection of the shift from the inherently political to the explicitly political not as a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy, but as proof that the gradual opening up of an art practice to its widening context almost inevitably implies its equally gradual, or sometimes sudden, politicization. Haacke’s great achievement is to remain—once that opening up of the artwork and the widening of its context has occurred—as aesthetically clear and factually precise as possible, while abstaining from clumsy didactics or narcissist posturing. In order to not close the work down again, but to keep it indefinitely open.

Jack Burnham, “Systems Esthetics,” Artforum (September 1968), https://www.artforum.com/features/systems-esthetics-201372/.