Charles Jencks was a pioneer of postmodern architecture—or “bastard classicism,” as his American detractors put it.1 In 1979 the American-born polymath and his wife, the garden designer and historian Maggie Keswick Jencks, purchased a large townhouse in London’s Holland Park and extensively redesigned it over the next five years. At once a family home and a “built manifesto,” The Cosmic House nods to Ancient Egyptian, Baroque, and Hindu architecture, modern science and urban planning, the Zodiac, western philosophy, and much else besides. Jencks integrated his eclectic references into a rich (and kitsch) symbolic scheme that sought to reconcile micro- and macrocosms: domestic pleasures and cosmic immensities; private gags and philosophical traditions. A cantilevered spiral staircase at the center of the building, for example, doubles as a model of the solar year with fifty-two steps for each week; at its base is Eduardo Paolozzi’s circular mosaic Black Hole (1982).

Leading off from this mosaic is the basement gallery, home to an elegant exhibition by New Delhi-based Raqs Media Collective. (Jencks was co-designing the gallery with his daughter Lily until his death in 2019; the museum opened to the public two years later.) Founded in 1992 by Jeebesh Bagchi, Monica Narula, and Shuddhabrata Sengupta, Raqs’s research-driven, cross-disciplinary work—in installation, poetry, philosophy, and curation—engages grand philosophical themes with sensitivity and understatement. Time is among them. Decorated with Jencks’s vatic concrete poetry and mirrors honoring Galileo and Copernicus, this gallery—run by Jencks Foundation artistic director Eszter Steierhoffer—aptly frames Raqs’s response to Jencks’s legacy, bringing the views from 1980 and 2023, London and New Delhi, into meaningful contrast.

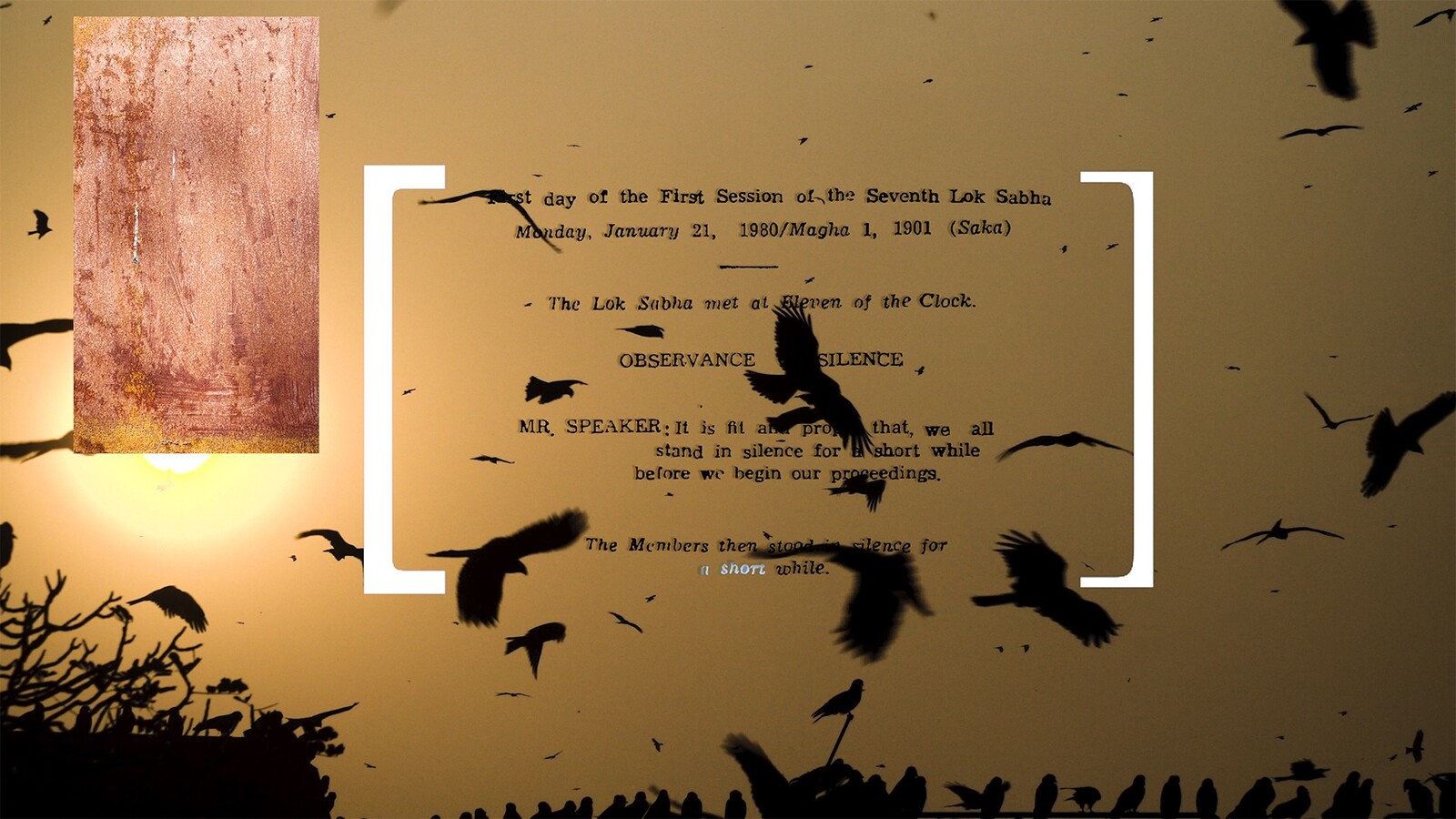

Playing on a flat screen at the room’s far end is The Bicyclist Who Fell into a Time Cone (all works 2023), a richly layered 25-minute video essay that forms the centerpiece of the show. The hypnotic central image is of a woman cycling in circles in various edgelands outside Delhi, the stark white dirt of which resembles lunar rock. Collages of found images—spacecraft, animals, fireworks, ephemera from the Delhi State archive, photos from Jencks’s trips to India—are animated across this new footage in a dynamic interplay of past and present. A meditative voiceover spoken by Narula dwells on historical events in the year 1980: a eugenics program to castrate bulls, a satellite launch, a plane crash. Meditations on fragile archives and fallible human recall combine to melancholic effect: “Memory without memory, that is our condition.” Yet to remind oneself that this is a causal universe is to imagine that a transcendent record may, in theory, exist: “Things might vanish from history, but they do not vanish from time.”

In his third thesis on the concept of history, Walter Benjamin imagines a chronicler “who recites events without distinguishing between major and minor ones,” and in doing so “redeems” mankind by returning to it the “fullness of its past.”2 Raqs’s video seems both to gesture towards and undermine this messianic conception of history. A wall text describes The Bicyclist as a “chronogram,” reflecting how the museum’s design superimposes references to different historical periods, and calling to mind Jencks’s “Evolutionary Trees,” in which he mapped architectural movements as they mutated over time. Rather than simplify the past to make it legible, Raqs’s chronogram presents history as a resonant ruin: a collection of fragments out of which subjective meaning might emerge. The ambient soundtrack suggests that archival traces are connected by affective registers as well as causal relationships.

Raqs’s exhibition is in part an act of revision, offering a parallax view to Jencks’s large-hearted, yet western-oriented, postmodern practice some four decades after the fact. (1980 marked the first Venice Architecture Biennale, titled “The Presence of the Past,” in which Jencks outlined his theories of postmodern architecture.) Framing the video are five large wall drawings—of mesh cages, flies, and bicycles—on reflective panels: components of a larger work scattered throughout the museum, titled Betaal Tareef: In Praise of Off-time (and its Entities). The sense of revision or interference is emphasized in the work’s second component, comprising three AR works visible via iPads dotted in various rooms. These translucent floating forms—one resembles a moebius strip, another a purple flower—sway above pieces of furniture, including Jencks’s former bed. Ambiguous and spectral, these “entities” seem to render visible the felt effects of past events (one possible meaning of “off-time”) on the building’s atmosphere.

That I did not come away from Raqs’s exhibition convinced that 1980 was a more significant year than, say, the one immediately preceding it perhaps reflects my own Eurocentric historical vantage. Rather, I read 1980 as a dot in a constellation, a place to view things from. Even such strictly delimited historical perspectives, Raqs’s work suggests, are permeated by coincidences, dead ends, repetitions—chaos, in a word, redeemable by art.

How that art gets made, in Raqs’s work and The Cosmic House, feels relevant here. Maggie Keswick Jencks designed the garden (accessible through an outside door marked “The Future”). Other architects, artists, and designers—notably Terry Farrell and Piers Gough—were integral to its design and decoration. The Cosmic House is a remarkably cohesive and stimulating temple to knowledge, but equally to the co-operation that makes learning possible. In contemplating his place in an unfathomable universe, Jencks was making meaning in a contingent present, with the ideas—and the people—closest to him.

Quoted in Edwin Heathcote’s A New Description of The Cosmic House (London: the Jencks Foundation, 2022). Before Jencks died he appointed Heathcote, a friend and architecture critic, to the post of The Keeper of Meaning.

Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History,” 1942 translated by Lloyd Spencer: https://www.sfu.ca/~andrewf/CONCEPT2.html.