Say Dod Dodde. Verbally fry and vocally claw down into the etymological gunk of the word lump; come to the Frisian Dod Dodde: lump, clump, bunch. A Dutch word, dot, is adjacent to this linguistic clump; it translates as “a bunch of twisted thread.” Under a clump of thread is a gunk class. They refuse to work … for the Someones. They gunk the thread; they clog the operation.

Under the operation. Under the class. Under stand. Standing on a Manhattan sidewalk, I am seven. I ask, “What is shooting up?” My mother replies and I translate the explanation into my own speak: Low, low, low. You feel low. You are UNDER everyone. You shoot UP. You lay down, like on this sidewalk, and you feel HIGH but your body is very LOW. Lowly, you lay, feeling feelings because there is no working because when we work hard we shelf feeling and we shelf being so when being high we suddenly get to be. My shooting-up-aunt, my Aint, my Aint Sister, as we might call an aunt in my mother’s family, my Aint Sister being like a lump on the ground gets to simply be.1 I have just seen Star Wars debut in the movie theater. I imagine galaxies unfurling inside my aunt’s head while her body is grounded, thousands of clusters of matter pushing towards and away from one another over millions of light years. No, this is not resting before work. No, this is not gathering your energies for a boss. Is her high a way of recovering from one hundred, two hundred years of Girl-Bosses and a hundred more to come?

Dot dot dot dod dod dod doddle.

Fred Sandback walks the same city in the same era.

Dot dot dot dod dod dod doddle. It is a fine day. But such a different terrain when you start to splice for class. Does the famous artist have a boss, a lineage of bosses bossing all the people who came before him, infinite bosses for infinite subordinates? Is subordination in his blood?! Does he shoot down, like a Spiderman, or does he shoot up, like a junkie? No, he makes work! He alpha-installs a thread. It is as light as a sketched line but very dependent on the infrastructure; it is suspended from ceiling to floor.

This is a way of being that is bearable for the elite; they float, in good health, among their things, among these strings. These things, their things have been cleaned for them, unless they have decided that it is meditative to clean. Who dusts the Sandback? And what dusted Sandback? Everything unbearable was supposed to slide down and away from the string.

(Imagine an image: Venice Beach, CA, US. 1970. My mother, age 15, shoots up into the bottoms of her feet. No trackmark. Erased drawing.) Sidetrack: a trackmark is also a drawing, is also a situation.

1847: Marx and Engels write, nearly intoxicated by their own feelings, about

the “dangerous class” (lumpenproletariat), the social scum, that passively rotting mass thrown off by the lowest layers of the old society, may, here and there, be swept into the movement by a proletarian revolution; its conditions of life, however, prepare it far more for the part of a bribed tool of reactionary intrigue.2

Some scholars decry this passage, deeming it “so vague it barely registers as theory.” I appreciate that the lumpenproletariat escape register evades accurate theorization. But Djemila Zenaidi and Jérôme Beauchez more precisely point out:

What is less well known, however, is the extent to which Marx’s open contempt for the Lumpenproletariat resembles the disdain they inspired among key Parisian figures of the counter-revolution, including Georges Haussmann … [both held in common] this common verdict of worthlessness concerning the people they saw as embodying the rejects if not the scraps of industrial capitalism.3

Pronounce the Early Modern Dutch word, Lompe. A rag, a tatter, a piece, a lump. Try sixteenth-century Danish: Lompe. Lompe is a block, a stump, a log. We are traveling along the coastline. We camp in a grove of redwoods. Inside a hulking, burnt out stump, my mother and her only grandchild make a bed. Lumpen in the Lompe, they dream. Deeper into the grove, in the glomming hour, I spy a white rag, a used wet wipe. It’s fresh. I track it. It belongs to the ass of a woman one campsite over. She wants to share marijuana and braided sage and trauma; she wants the redwoods to recede, obfuscated by her story. She will tear herself up in the telling and by listening, the listener will be torn up. Together, teller and listener will hold the tatters. It isn’t therapy-adjacent; it will not organize the trauma or the labor that traumatizes them. They will put the fire out. They will piss and wet wipe. Then, all of a sudden, it will be dawn.

1890: Cooperative socialist anarchists of the Kamawea Colony log giant redwoods in order to realize their collective dream of an economic collective. Together, they spare the largest Sequoiadendron giganteum from the blade and dub it “The Karl Marx Tree.” They say they want no king, but they also want no loafer. No lumps amongst the stumps? Just workers without bosses.

(I am a lump Dear Reader, you too? I took ten years to write this. Maybe you take ten years to read it, too. There are no bosses after our most thorough clearcut; no one tracks your reading on a work app. The speed-readers are: down in the dumps; in the shade of the fka Karl Marx Tree fka General Sherman Tree; resting under 2,100 tons of dead tree.)

1911: Lewis Hine, investigative photographer for the National Child Labor Committee, arrives in Winchendon, Massachusetts to document visible violations of the child labor laws. See a string; it wends its way from loom to girl; now get a look at the scores of kids laboring for the White Brothers’ cotton twill mills. These kid-workers and their worker-parents are from a community of informal crossers that cross the international boundary line, paperless.

Adolescent French Illiterate, Hine annotates. Rooted up from their farms, journeying from north to south to get to New England factories, they are hired to work the line.4

Many of the children in Hine’s photographs cannot read official visas in any language. Lists and laws must be rote, held in their minds. Small untruths worm the photos’ backsides. Literate Hine incorrectly writes a little worker’s name down.5 For reformer or cop, all evidence does not condense on the surface of the photograph; also, it does not solidify into any language. Inside the mill, the machinery shakes the building, and it is unbelievably hot and deafeningly loud.6

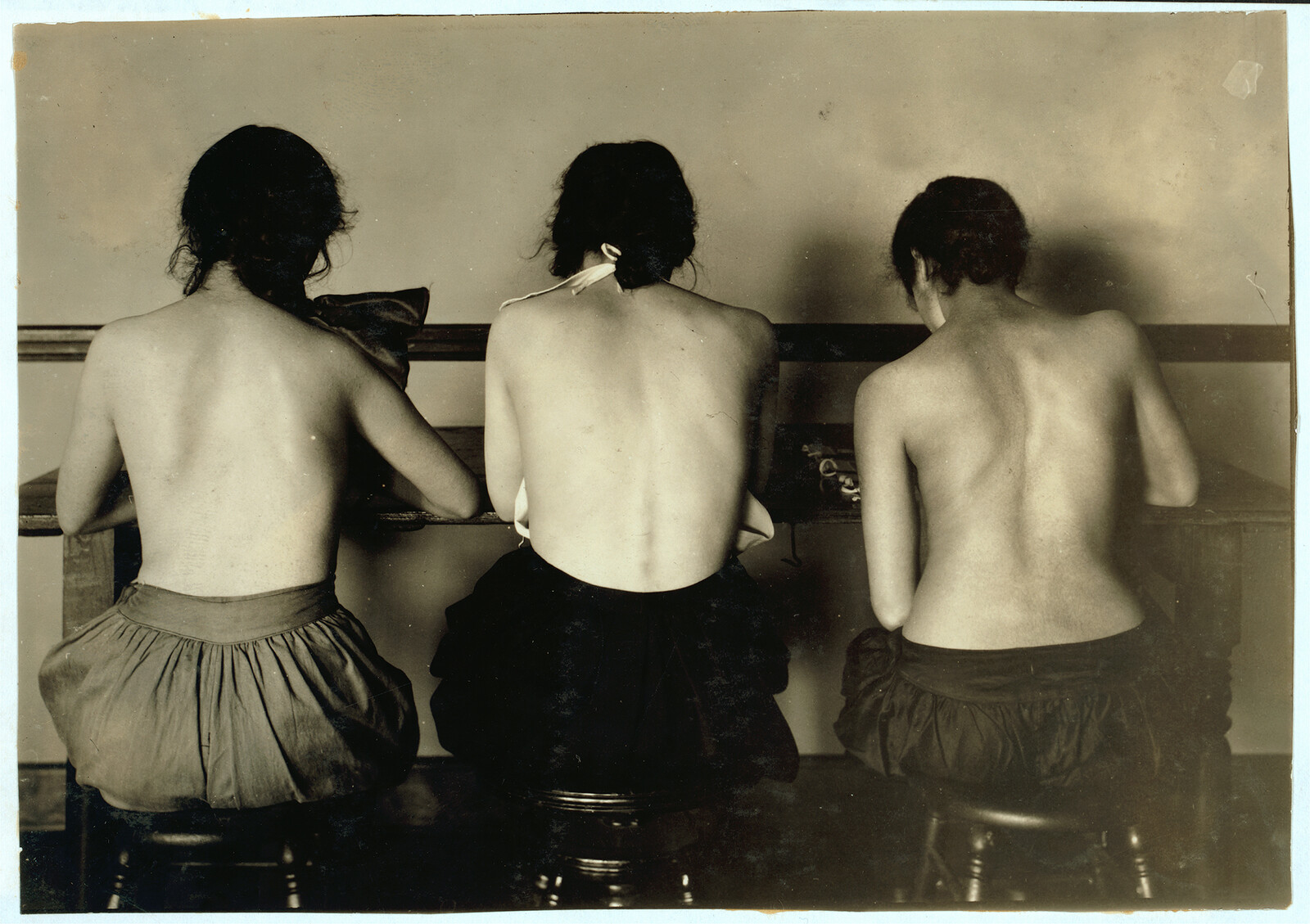

Later, Hine’s lens reaches the girls who read numbers for a living. Photographs of the naked backs of girl accountants, working in Eastern Massachusetts, emphasize the curvature of their spines. The work has spoiled the spine’s line.

1912: The Highlands, which was in operation when Hine traveled to Winchendon the year before, shutters in 1912. For forty years, the private sanitarium housed capital’s other shadows: the nervous, addicted, strung-out, and unproductive elite, and sometimes wrecked war veterans. In an advertisement for the Highlands, in the Journal for Inebriety, a former Civil War surgeon named Dr. Russell claims that patients are not subjected to “common nurses but are provided with companions.” It advertises to ladies that an “intelligent American woman” will work to be your friend. Will she or won’t she disentangle you from troubling lumpen lines?

1924: The local female auxiliary of the Ku Klux Klan strut through Winchendon, small crosses encrusted with red stones around their necks.7

This spring, and through the summer, the KKK will hire a plane to fly over larger area rallies in the night. The plane is decorated with a thin line of red lights. The understanding is that they are targeting Jews and Roman Catholics. Recall the adolescent illiterate French and the men who have graduated from itinerant tinker to small-town merchant. I was relieved to read that sometimes, that year, they, too, clustered and repulsed their attackers. The local papers describe a Klan meeting where all the vehicles are parked in a circle with their headlights facing out. The Klan nestles, outside, in the center, amongst the taillights. And the Anti’s, those gathered to protest the Klan, are caught in the blinding beams. The Klan observes their neighbors suspended in the long lines of light. The Anti’s cannot recognize an overseer, a customer, a pastor, a schoolmate.

March 14, 1925: Four Klansmen ride through the center of the town on horses. They seem likely to have galloped past the future site of the Fred Sandback Museum, past buildings that will become vacant lots and paved parking spaces. The riders are followed by one hundred vehicles.8 This is when the town is dense, hectic, charged, and energetic … the whir of industry still whirs. Five train lines converge here. Central Massachusetts woods still supply the manufacturers of toys and tools and cabinets. Throngs of white proletariat absorb, repulse, or recycle Klan feelings: a mess of unsorted emotions about the recent pandemic, the recent war, and the recently crushed labor movements.

Fifty years pass and there are no throngs to sop up violent emotions.

Add thirty-five more years. On a road that runs north to the state line, a large white sign with hand-painted black letters reads: TONY IS A DRUNK. Several years pass and more language materializes: AND A THIEF. Micro-emotions are kindled in the tourist cars of the remainder middle class heading north: amusement and discomfort. In NY, a writer who knows I also travel this same route asks if I know the story behind the sign. Not even Reddit knows.

1956: The White Castle is demolished because there are no buyers.

In 1888, the twenty-eight-room mansion, christened Marchmont, was erected by the White family who own the White mills. Locals insist on calling it White Castle. Like the late-night midwestern burger joint. Descendants of the castle, owners and servants, disperse east and west. An erotic BDSM e-book, e-published without date, is situated in the same castle—except the author has added one room and at least one captive. The e-cover features a naked woman trussed up in a dungeon. If I could get a deep look at her fingernails and earrings, I could identify her status outside of the dungeon: Lumpen, proletariat, or bourgeoise? Maybe guillotine decals on pointed press-ons over naked nails bit to the cuticle.

James Pierce, Earthwoman, 1977.

1970: Just before and north, on a farm in rural Maine, James Pierce creates and then abandons twenty earthworks (1970–1982). Forms are not formal. Pierce pilfers from and remixes mortuary and military structures; he channels the slobbering whimsy of R. Crumb, including in Earthwoman: sprawled, thirty feet long and fifteen feet wide, face down. As the sun rises on summer solstices, it aligns with the split in her buttocks. Locally, these disintegrating abandoned shapes become associated with satanic ritual. Pierce’s land art gains semiotic thickness within the tight radius of the township only after the maker deserts the site.

1981: The Dia Art Foundation granted Sandback funds “to establish a space … selected specifically to accommodate the scale and spatial needs of Sandback’s sculptures and sculpture series.”9

Sandback delivers his “Junior”: the Fred Sandback Museum; like the owners of many small businesses shuttered or ailing around his selected site in Winchendon, Massachusetts, he names his enterprise after himself. To elide oneself with institution is risky business—the entrepreneur née artist is fused to a structure that is outside of the limits of his body. Whether or not the institution inflates and/or collapses, something in the core structure of the artist amalgamate is deleted (recall that the linguistic definition of “elide” refers to the deletion of the vowel within a word). The titular head beheads itself; Sandback or anyone.

The Fred Sandback Museum: 74 Front Street, Winchendon, Massachusetts. It begins.

1985: Dissimilarly, the Fred Sandback Museum was not thickened by local inscription—an inscription that retains looting and scarring by drunk and rutting teens. But when the Fred Sandback Museum was in operation, it was also closed—open only by appointment. Pedestrian Townie did not come off the sidewalk and get rid of her narrative self by hunting the line across a void. Cool Puritan sublimes were not advertised; I lived one town over and I was oblivious to the self-sealed site. We miscreant and working class twelve-year-olds were bussed to Boston’s Renoir exhibit on some do-gooder’s dime. We absorbed, into our substrates, images of pink small girls with lap dogs on laps. Separated from the group, I placed my flesh palm against a stone palm. It was an ancient religious sculpture. The guard cried out.

1995: A Dia pamphlet on Fred Sandback shows a plain, empty studio in Rindge, New Hampshire.

In 1995, another castle is erected by a New Hampshire state representative in Rindge, NH.

Both castle and studio are situated on dammed rivers several miles north of the former White Castle.

The ’90s castle was built to resemble a Lego and granite version of a gothic castle with 65-foot tower and secret passageway. It runs on solar, and it is for rent. POWERONE, the author of Marchmont Castle, might set up in the tower and write their e-rotica sequel there. 10

1996: Fred Sandback liquidates The Fred Sandback Museum.

He kills the brand, the father, and the outlet.

The burning question is whether, after selling the building, he returns the seed money to Dia. But it might be venture capital on the trustees’ part, as it is only sucker lumpen and decaying working classes whose debt is forever.

2002: After a screening at MoMA, I am introduced to another attendee—a filmmaker who was raised in Winchendon, Massachusetts. Like me, the person might be lumpen, queer, and brainy. I ask: “As a kid, did you ever go to the Fred Sandback Museum?” The filmmaker laughs: “IF ONLY! What an opportunity that would have been, eh?! Never was open.”11

Sandback hoards his spare anti-narrative, slow releasing it to bloated collections? Sandback fears a lumpen joke about string at his expense? Sandback is depressed and disappearing? I never run into that hometown filmmaker again, in Winchendon or New York City. The internet is clean of them.

2003: Sandback commits suicide.

2011: We cross the state line and locate what had been his summer cottage on the pond.

Our near trespass will not be like old crime pulp, where I might place my pale schnoz in a wet footprint and breathe in deep, where I could tell you how many hours cold the track is and if that walker were full, or hungry. We will stay gazing from within the locked car. Are we like Nana, symbolic plebe—that golden fly, buzzing at the edge? No. So far, we are so deactivated … just maggots in the shaded perimeter.

Because we do not have access or invitation, we have sieved online data and old phone books to establish the position of Fred Sandback’s house. Our gesture is similar to media and military tactics, except we maggots haven’t really mobilized. There will be no organized killing of capitalists in the trees. If there was a soundtrack, an invasive thrum. Instead, a blue jay jeers: The owner of the cottage is long dead! So, is this a pilgrimage to an offbeat shrine? Not so much. I will realize, years later, that we were assessing the score: the cottage was like a baker’s dozen of extra homes for the wealthy. Realize: we lumpen don’t need to apologize for tallying their hoard. We are reversing the ancient moment when the king’s tax collectors located our fields and assessed our crops. Tally-ho.

(The moment we spy the structure is cloudy, quiet, and pleasant. Maybe Sandback’s patronym is carved or painted on a wooden board and nailed to a tree. This is a common practice here. Sometimes there are many signs on one pine and reading each aloud, from top to bottom, is a dumb and jolly pastime: a WASP mantra to detach from the reality of your spoils.)

At the edge of the Fred Sandback property, I remember thinking: He thought a line was something habitable. Until he didn’t.

2012: Jeanne and Michael’s 8,000-square-foot glass house abuts the Santa Fe National Forest. I find myself inside, on a tour of their collection.

A beautiful, plain, dark jar is on a shelf that is almost between rooms. I stand there next to it. There is only room for one body. This object is situated on its mute side. I cannot see a signature. Someone walks by and says, “That’s Dave the Potter.” And keeps walking. In this place, the logic is that each object is also an avatar of its maker?

The jar was thrown by David Drake. In 1801, he was born and enslaved in South Carolina. Drake signs his pots, Dave. Because this domicile is more museum than house, I don’t know if the vessel is one of forty among 40,000 that has a bit of text inscribed in the clay. Currently, each inscribed jar sells for $175,000. The money is passed between auction house and collector.

Front:

I made this jar for cash

Though its called Lucre trash

—DaveBack:

22 August 1857 / Dave [—David Drake]

People are around me in the hallway again, having returned from the Goldsworthy located beside the house. They say he threw a fit during install and threw his chainsaw. It is art world gossip, but it also shakes up the Texas Chainsaw Massacre trope—a white man with an unleashed chainsaw, the chain actively rotating across the blade while hurtling through the air, is simply an agitated English sculptor who is more renowned for gently arranging dew and dust.

David Drake. James Turrell. Donald Judd. Sandback. Andy Goldsworthy. Kiki Smith. All glom together. It is as if a cyclone in my head has left them in a hunk. Can the thread be extracted, not unlike the cook’s hair pulled from the chewed meat in your mouth?

January 1, 2014: At 61 Weller Street, Winchendon, a 3:00 a.m. fire burns down a multi-family apartment building, formerly that “home style” sanitarium called the Highlands. The water lines are frozen. Firefighters can’t pump.

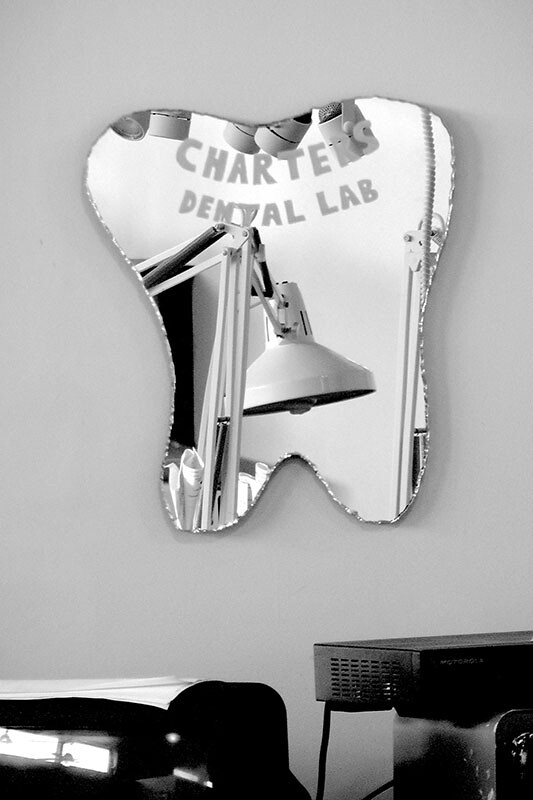

Photo note from the artist visiting the carapace of the Fred Sandback Museum, 74 Front Street, Winchendon, Massachusetts in 2015.

2015: The carapace of the Fred Sandback Museum, at 74 Front Street, remains. To take a comprehensive picture of the shell, one must stand in the path of oncoming vehicles. Winchendon, Massachusetts is a post-industrial town of 10,000; still, traffic flows. “Terry” Charters bought the building directly from Sandback, and it remains Charters Dental Labs. Dental implants and their attachments are manufactured in the front rooms; holiday ornaments are stored in the back rooms. In the basement, pamphlets from The Fred Sandback Museum ephemera stuff an old bank safe inside of a vault. Charters relays that the combination to the locked safe is lost. He offers to let me and my baby into the chamber. I don’t want to go in. What is now a lab was a museum was a bank was a field. A pale yellow moth flutters across Front. Through a satanic field. Past satanic mill. Moth brethren to moths caught and pinned by Dr. Russell’s son one hundred years ago.12 Its path is erratic.

By December 2022, Lisa’s Paparazzi Room will offer nickel-free jewelry for sale at 74 Front Street. How does jewelry connect to the word Paparazzi? With shame, I imagine myself as a sort of FSM Paparazzi. I stake out. I expose. My schlong is my long lens. In the downtime, I practice failing pickup lines.

2016: Sentence is line; page steadies line. A line steadied by kerning and leading. Glue the sheet to the dark blue ground. Its sonic mass is distributed across the syllables, phonetically. It’s easy to tell the depth of a well. A Fred Sandback is a line that divides the volume of a room. In some imagination, air has been balanced.

An aesthete, recipient of trickle-down American Buddhism, comes to the Sandback through the museum (St. Louis and DC). There, the aesthete was/is relieved of language and gender and is stripped of representational reckoning. This is no small grace, ontological or libidinal.

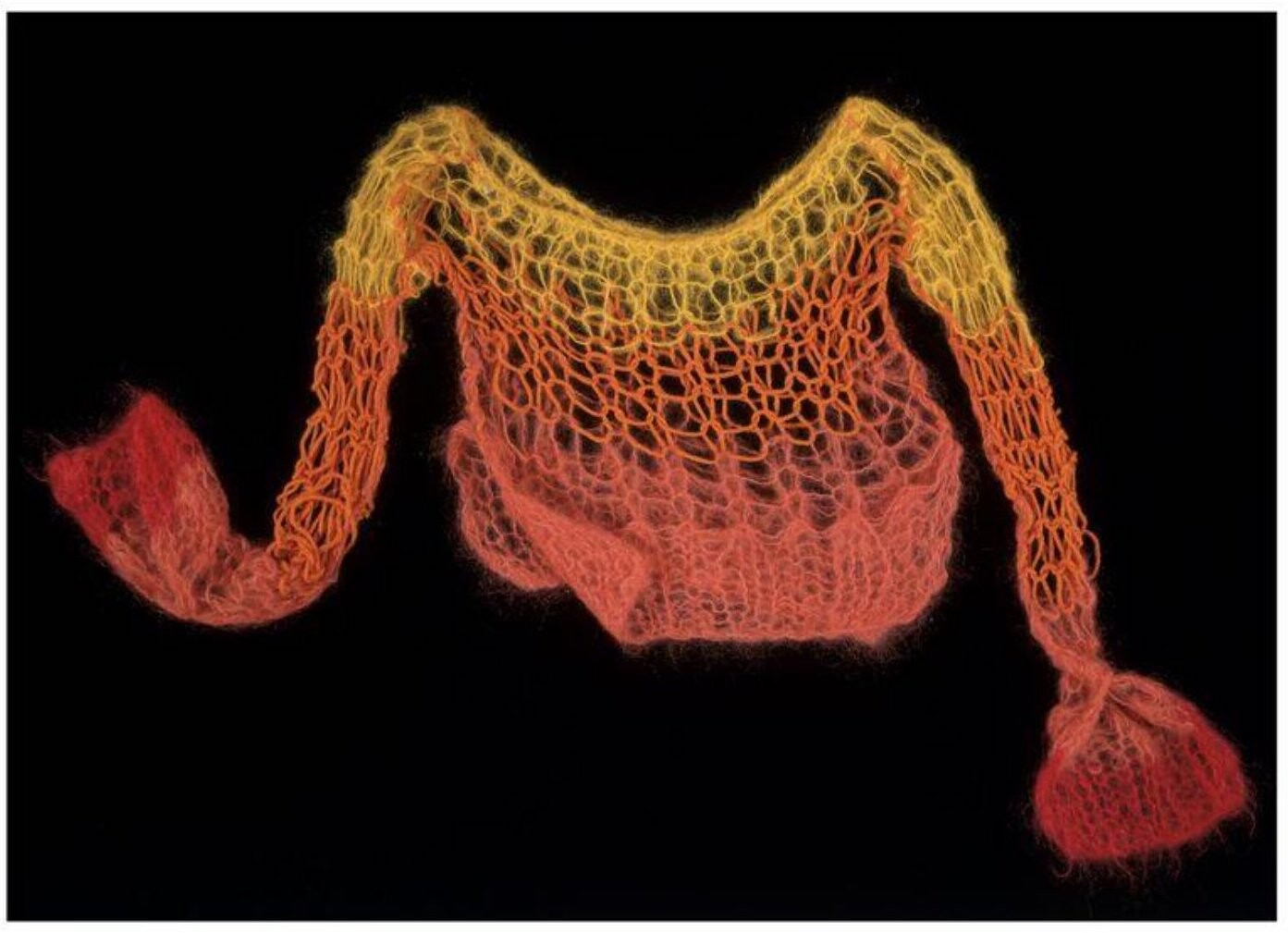

2017: I am in a private conversation with a curator. We dish origins: she sketches out her own American working-class history; I detail my own lumpen gutter lineage. I mention that I would like to write about the Fred Sandback Museum as a class problem. I have a draft in hibernation. The curator tells me that Amy Sandback, wife of Fred Sandback, once invited the curator to her Manhattan apartment and insisted that the curator leave with one of Amy’s own sweaters. The curator begs me to not publish this article until after Sandback’s death. After Amy’s death. How long after her death do I wait? I should have asked. Maybe, instead, I glibly remarked, What a sweater! Its nubby arms seem to have quite a reach … to smother, in absentium, my laptop keyboard, my printer, my submitted text.

I could scrawl a diagram of an old carnival game called Whack-A-Mole and write in careful penmanship underneath: Is the curator a class traitor, or is it maybe me betraying her? But we are not from the same zone; she began working class and I began lumpen. The curator fused with the ruling classes. Is she attached to their ass or head? No, it’s the agony of being double-fused between the two.

Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood, jumper with red, orange, and yellow loose-knit mohair, from the ”Seditionaries” Collection, 1976. Photo: The V&A Museum. Jumper purchased with assistance from the Friends of the V&A, the Elsbeth Evans Trust, and the Dorothy Hughes Bequest.

There is something now, in reading my childish linguistic knitting together of the attempt to conceive narcotic states, that evokes the adolescent sensation of reading the opening monologue of William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury. The novel features Benjy, once Maury, a boy who operates in another register than the normative. His name is changed by his mother when it becomes clear that he communicates outside of the pale. I recall, too, while reading, the feeling that I was at the edges of comprehending Benjy’s metabolization of place. White and wealthy Benjy is no lumpen; but he is a portal into a furtive space where a stubborn growth of language only hedges at an experience that is marginal and unmanageable. At sixteen, I mistook my attachment as something regional and racialized—that we, Benjy, me, my aunts, my mother, were sutured together by white rot alone; we were something spoiled in the hot, wet shade, but still alive (swelling) and vocal (crooning, babbling, screaming). In 1910, in 1923, in 1954, my family, lapsed southern Baptists and excommunicated Mormons, were dirt poor cotton sharecroppers. I welcomed Benjy into my familial swill because he was outcast by the plantation elite. At this juncture in time, I think the organizing margin is class—a deep, lovely, fetid alliance with those of us from another zone, not necessarily southern and not necessarily white, that repulses the supposed rewards of good behavior. Adieu, Maury?

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Manifesto of the Communist Party, trans. Samuel Moore, English edition of 1888.

Djemila Zenaidi and Jérôme Beauchez, “Sur La Zone: A Critical Sociology of the Parisian Dangerous Classes (1871–1973),” Critical Sociology (2019): 1–18.

At a certain juncture, between 1840 and 1930, approximately 75 percent of the population of Quebec temporarily migrated to New England, transitioning from an agricultural work force to an industrial one. Half returned. Looking at the obituaries of workers-who-stayed in the local Winchendon Courier, one notes an emphasis on language acquisition and the melting of the French patronymics into something that is not formally French or English. One obituary of a Quebec orphan carefully notes: “She taught herself to read, write, and speak in English.” This is very far away from the long-ago peasants of Languedoc, signing a legal document by scrawling a quick sketch of a tool to stand in for their signature. The end of the peasant?

An incorrect spelling of a child’s name is probably not enough to elude authorities looking to crack down on labor infractions. However, Hine’s documentation of underage workers in Lawrence, MA frequently misses names and misnames others. Some of this can be attributed to a rapid conversation between photographer and worker, to workers’ subterfuge, to children taking the piss out of a stranger with strange requests, but also to the way in which sharing official identification papers was common practice in immigrant communities at that time.

I lived near the remains of the Lowell mills. At the national historic site, attendants—sometimes former workers—will gun up a fraction of the looms and it is deafening. Everything vibrates. Me and my baby wore noise-reducing headphones and still the din leaked in. A text-based display panel described widespread hearing loss amongst long-term workers. I begin to wonder how language acquisition and emotional cultures were shaped by temporary deafness on the job and long-term hearing loss after the job. There is a New England stereotype of the stoic, silent working-class grandparent that might need to be revisited in light of the impact of industrial worksites →.

This information comes from a private local history social media group. A senior user described how his aunt was a member of the KKK’s ladies division in Winchendon and how she had asked his mother to send red stones for these crosses. He also described another aunt, perhaps from the other side of the family, who was Catholic and was forced by the KKK to abandon her home in Florida, Massachusetts.

See →.

See →.

Before this castle was for rent, the owners used to throw an annual Bastille Day Party on the shores of their beach. There was a picnic and professional fireworks. Not unlike the way the various global iterations of gilets jaunes (née yellow vests) rotate from far left to far right, restitched into near wrong … it was unclear as to whether the picnic was commemorating the end of kings or mocking the revolutionary mob who stormed the prison. CACA- PEE-PEE- CAPITALIST! CACA- PEE-PEE! CACA! CAW CAW CAW!

After publication, I pulled up an email from 2016. It was written to a woman who, like me, had fled the area. If one goes by Linked In, my route was more rough-hewn than her ivy-league escape chute. When I was fourteen, we went to a Cure show in Worcester together but we have not spoken since 1991. I can still summon the smell of her laundry just out of the dryer. In the email, I wrote about my interaction with the only other person I have met from Winchendon since leaving the area and I see that my reconstruction was in error. There is more. Here is I am referring to meeting the hometown filmmaker at MOMA: “I don’t recall their name. They said they were shocked when they found out the Fred Sandback museum was in Winchendon and felt a sort of class melancholy- a sense of being robbed of the possibility of contact with these works as a working class kid in Winchendon that was strange and needed other strange things.” A sort of class melancholy. The town was mossy with that. a sense of being robbed of the possibility of contact with these works as a working class kid in Winchendon. The filmmaker pinpoints that there is no Robin Hood situation in this place. They can’t break in (very high windows) and feel. It is an old bank. When I went on my tour of Charters Implants/ Fred Sandbook Museum he said the old safe was stuffed with Museum ephemera that never got handed out. Sandback said himself, “My work is ‘about’ any number of things, but ‘being in a place’ would be right up there on the list.” This is a pull quote from the David Zwirner website press materials accompanying the Fred Sandback show that opened on April 1, 2022.

Smithsonian Collection.