In 2014, the year when the Russian war against Ukraine started, Lyuba Yakimchuk wrote a poem titled “Decomposition.” The poem shows what the war is about: ruination and destruction. Yakimchuk writes: “don’t talk to me about Luhansk/ it’s long since turned into hansk/ Lu had been razed to the ground/ to the crimson pavement.”1 Yakimchuk decomposes the names of cities in the same way they are splintered into parts. There is no Luhansk anymore: it is only a fragment—“hansk”—that remains. She continues, about Donetsk: “my friends are hostages/ and I can’t reach them/ I can’t do nestk/ to pull them out of the basements/ from under the rubble.” At the time of writing, 21,293 civilians and more than 100,000 Ukrainian military personnel are reported to have been killed since the beginning of the invasion on February 24, 2022. The scale of the devastation of human life is likely to be even greater, but due to the ongoing destruction and inaccessibility of territories under Russian occupation, it is impossible to know the exact numbers of victims, of those who are in those basements or under the rubble. Lost lives cannot be rebuilt. The human psyche and culture has, however, developed mechanisms to cope with loss. This is the work of the living to mourn and remember. But the lives of the dead will be never repaired. Reparation is a gift to the living, those who can repair and reconstruct their lives and their environments.

War also brings the ruination of culture. Russia targets not only Ukrainian lives and Ukrainian statehood, but also Ukrainian identity. When Putin and his officials speak about the “de-nazification of Ukraine,” they actually mean de-Ukrainization.2 The destruction of culture and Ukraine’s cultural heritage is a part of Russia’s attempt to eliminate Ukrainian identity.3 At the time of writing, 553 objects of cultural heritage and cultural institutions have been registered as destroyed in Ukraine as the result of war.4 But the ruination of Ukraine and its culture is not limited to physical places, buildings, or cities. Language is also maimed by war. Yakimchuk’s own place of birth, Pervomaisk, “has been split into pervo and maisk/ into particles of primeval flux.” Yet her poem demonstrates that even shattered language can create meaning. The simultaneity of decomposition and recomposition shows that creation happens in parallel with destruction. Rebuilding does not come after the catastrophe, but happens during it.

Rebuilding is a condition of survival. As Russian missiles continuously ruin Ukrainian infrastructure, Ukraine rebuilds it again, providing water, electricity, and mobility. In the same manner, since the first weeks of the invasion, professional communities of museum workers, heritage specialists, and curators have done everything possible to save Ukrainian cultural heritage, museum and archival collections, monuments, and architecture. Already in March 2022, religious scholars initiated the project “Religion on Fire: Documenting Russia’s War Crimes against Religious Communities in Ukraine.”5 The Ukrainian branch of the International Council of Museums (ICOM) started documenting cultural objects at risk.6 And several projects for saving cultural heritage were initiated in collaboration with large international actors such as UNESCO.7

Kherson Museum after Russian troops left the city. Source: Bropy.

To continuously rebuild, people need to be resilient. Ukrainian resilience was something no one in the world counted on when the invasion started.8 The word “resilience” was originally used in physics, where it meant the the ability of an elastic material to absorb and release energy as it deforms and springs back into its original shape. The word itself derives from the Latin “resilire,” which literally means “to jump back” or “to leap.” In Yakimchuk’s poem, language is deformed by war, but at the same time it “leaps back” to its original function of conveying meaning. When she writes “where is my deb, alts, evo/ no poet will be born there again/ no human being,” we can still decipher the name of the city that was the site of a major battle in Donbas in 2014–2015, Debaltsevo. Despite its destruction, Yakimchuk’s use of language still produces sense, “springing back” to its initial form. In the same way, under the horrendous conditions of war, millions of people have been forced to “spring back” and do the work needed to preserve and defend the “shape” of their lives. And now, after a year of Ukraine’s resistance, hardly anyone questions the Ukrainian willingness to defend their freedom. But why did so many experts, commentators, politicians, and journalists underestimate Ukraine, and overestimate Russia? This asymmetry was especially striking for people like me: those who come from Ukraine but who have been living outside of the country for many years. As a Ukrainian I had no doubts that Ukraine would fight. At the same time, I wondered what I did wrong that people around me could not see what for me was obvious? Why did we have such a different understanding of the situation?

One common thing that I and many Ukrainian colleagues have experienced after 2014 is epistemological distrust. Somehow, the fact that we come from Ukraine has made us unreliable in the eyes of journalists or other scholars. As Ukrainian media and communication scholar Volodymyr Kulyk put it, we are often invited to represent a “Ukrainian voice,” while others are invited to give critical analysis and evaluation.9 Ukrainian scholars are put in the position where they first have to (re)build trust, and only then can they build their argument. People who have studied the country or region for decades, who have knowledge of the languages spoken on the ground, who follow discussions in real time should not be trusted less, just because they might not be able to claim the privilege of emotional (as well as geographical) distance.

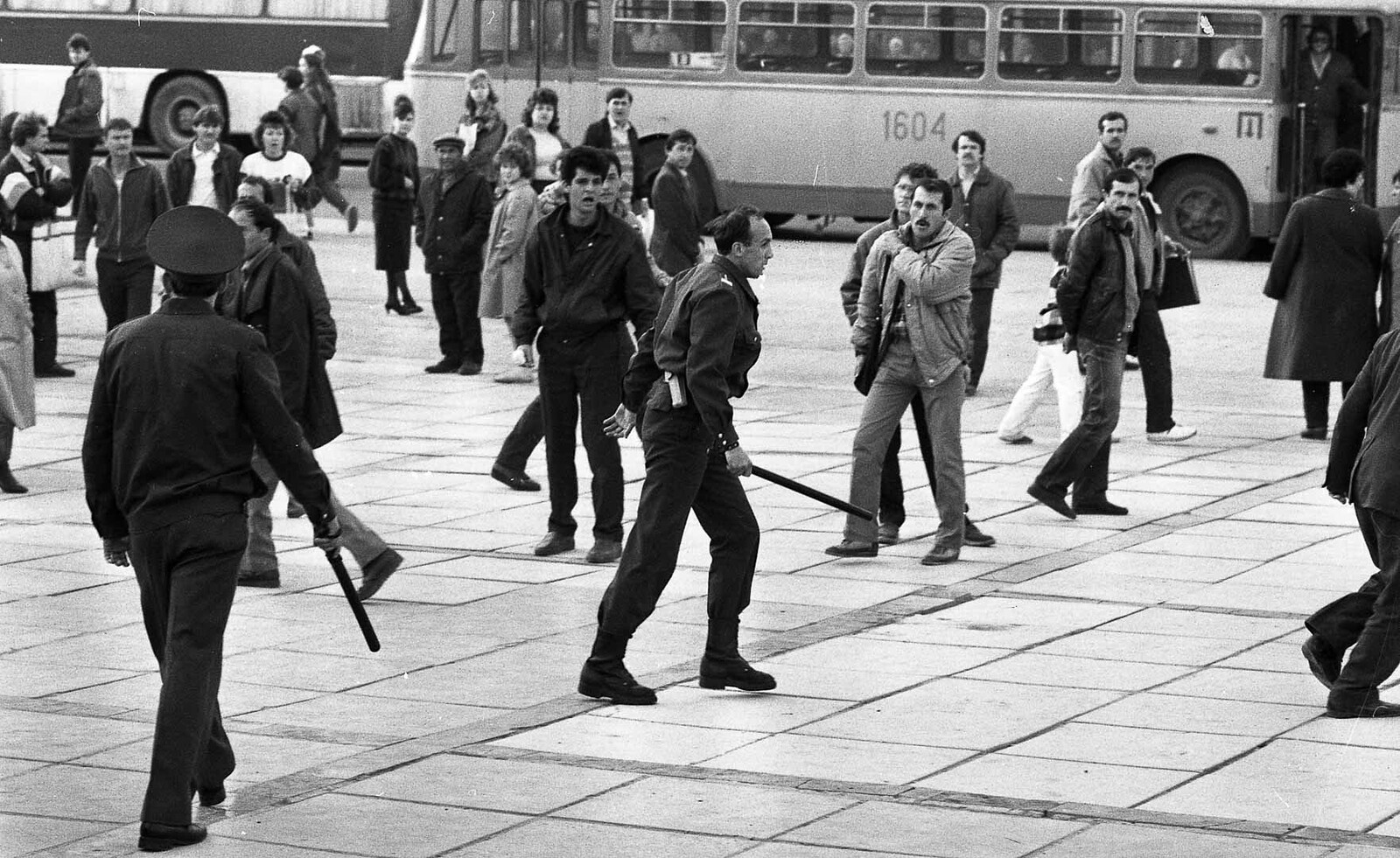

The roots of asymmetric knowledge lie in the way we learn and experience history. Through teaching, I have observed the tendency for the Soviet Union to be presented as an alternative story of modernity: that Stalinism was of course hard and unjust, but then everything gets better; the progress of modernity prevails. But terror and oppression did not stop with Stalin. In 1985, the same year that Gorbachev launched the program of Perestroika (which in Russian means “reconstruction,” and which aimed to build “socialism with a human face”), Ukrainian poet Vasyl Stus died in detention as a political prisoner for his poetry, which the Soviet regime determined was “too nationalist.” When students learn this, it is often difficult for them to comprehend the scale of the Soviet terror. The books they read tell them that everything negative about the Soviet Union finished with Stalin’s death in 1953. But the Gulag existed almost up to its end, and it was only at the end of 1986 that Gorbachev rehabilitated all political prisoners. This goes a long way to explain how a political system based on the Gulag survived, why there are so many political prisoners in Russia today, and why Russia uses the “nationalist card” against Ukraine to justify their unprovoked war.

Ruins of the Museum of Hryhoriy Skovoroda, Ukrainian philosopher of the 18th century, in Skovorodynivka, Kharkiv Oblast, destructed by Russian missiles. Source: Leonid Logvinenko via Facebook.

Ruins of the Museum of Hryhoriy Skovoroda, Ukrainian philosopher of the 18th century, in Skovorodynivka, Kharkiv Oblast, destructed by Russian missiles. Source: Leonid Logvinenko via Facebook.

Ruins of the Museum of Hryhoriy Skovoroda, Ukrainian philosopher of the 18th century, in Skovorodynivka, Kharkiv Oblast, destructed by Russian missiles. Source: Oleg Sinegubov via Facebook.

Ruins of the Museum of Hryhoriy Skovoroda, Ukrainian philosopher of the 18th century, in Skovorodynivka, Kharkiv Oblast, destructed by Russian missiles. Source: Leonid Logvinenko via Facebook.

Being born before the collapse of the Soviet Union, I, as well as many others who have experienced life behind the iron curtain but outside Russia, have never had any illusions about the Soviet Union. Ironically, Russia, the country that for decades has built its politics on the cultivation of nostalgia for the Soviet Union, is now practically erasing the remaining Soviet traces in Ukraine.10 In a way, Russia is committing the largest act of de-Sovietization (or “de-communization”) in history. The Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Plant, the South Ukraine Canal, and irrigation networks in southern Ukraine that were all part of Stalinist industrialization projects and which are vital for the needs of millions of people, are under constant threat of Russian missiles. And the Azovstal Iron and Steel Works plant, which was similarly built under Soviet rule in Mariupol in the early 1930s with bomb shelters, was subjected to constant shelling when it was used as a refuge for thousands of civilians and military personnel over 82 days starting in March 2022—just this time the shelters were protecting against Russians rather than against Germans.11 Quickly becoming a symbol of Ukrainian resistance and Russian terrorism, Azovstal became heritage simultaneous with its siege, and its steel synonymous with the strength and resilience of its, and Ukraine’s defenders.12 At the same time, Russia presents Mariupol as a symbol of rebuilding the cities that Russian troops destroyed. According to Ukrainian authorities, there have been hundreds of Russian construction workers in the city cleaning up rubble and starting to build new housing and infrastructure.13

When Russian troops leave the occupied cities, they loot museums and archives.14 Mathew Campbell writes that over the past year we have witnessed the biggest looting of cultural property since the Nazis.15 Archives are a crucial part of cultural heritage. They carry a subtle potentiality of history that can be written. With the destruction of archives, we lose the potential to reconstruct the past. For many years, scholars have used Ukrainian archives to write the history of the Russian empire or the Soviet Union, given that many Russian archives have been censored or closed. In this way, archives from the countries that often are treated as the empire’s periphery have already been central to writing the histories of the Russian empire or the Soviet Union. These “peripheries” have potential to shed light on the most illustrative histories—those which place Ukraine and Ukrainians at the center of Soviet history while at the same time testifying to their off-center position within them, and to their capacity to deconstruct hegemonic Russo-centric narratives. It is perhaps no surprise, then, that in this war, archives and libraries are attacked.

Looking back at the year that passed since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, it is easy to see that one distinctive perspective used in the discussion of Ukrainian history and heritage was decolonization. It is no coincidence that when people feel their existence is threatened that they started re-evaluating historical narratives. To this end, Ukrainians recall previous struggles for independence, from the Cossack wars in the seventeenth century to attempts of establishing statehood from 1917–1922. Mnemonically, everything can be recomposed into a linear narrative of resistance against the imperialist colonial power. When I was working on my doctoral dissertation some fifteen years ago, however, and referred to post-1991 history-writing as a postcolonial process of reclamation, I was often met with a sense of shock.16 “We were not a colony,” many (Ukrainians) reacted. But now, when it has become more commonplace to speak about decolonization in Ukraine, I use this term more carefully.

It is important to recognize the differences between the histories of Russian and other empires, as well as the specific place of the Russian empire vis-à-vis other colonial powers. As the transdiasporic Circassian-Uzbek feminist thinker Mladina Tlostanova and Argentinian semiotician Walter Mignolo mention, there is a complex network of imperial and colonial differences that include both external differences—between Western empires and the Russian Empire/Soviet Union (in which the latter felt inferior vis-à-vis the west)—and internal differences—in positionalities of colonized subjects under imperial rule.17 Moreover, there are also clear differences between the situation of Ukraine today and that of the postwar years, when writers like Franz Fanon and Edward Said were elaborating their theories about the post-colonial condition. They—Fanon and Said—were working in the centers of former empires, the metropoles, and were both influenced by and worked together with intellectuals in these places. This is not a point of critique, but instead, a recognition that western intellectuals supported anticolonial struggles and anti-imperialist critique.

Today, though, there is no common understanding about the imperialist nature of Russia among either the political establishment or intellectuals in western democracies. Nor do we witness broad self-reflexive discussions by Russian intellectuals. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, there have been no tectonic shifts reconceptualizing Russian or Soviet history in a manner or scope of the anticolonial critique that developed in Europe after the Second World War. In Ukraine, post-colonial critique was mainly limited to a group of Eastern European literary and cultural scholars such as Vitaliy Chernetsky, Tamara Hundorova, and Marco Pavlyshyn. Although groundbreaking in their approach, their critique did not create a public debate until 2022, when discussions on postcolonialism and decoloniality led to a wider societal reevaluation of knowledge about Russia and Ukraine.18 Alexander Etkind’s Internal Colonization: Russia’s Imperial Experience (2011) similarly failed to provoke a critical reconceptualization of Russian imperial history in relation to its colonial subjects, or a critical re-reading of Russian literature in either Russia itself or the field of Russian studies. The Polish-American Slavist Ewa Thompson’s Imperial Knowledge: Russian Literature and Colonization (2000), however, has served as an invaluable source for understanding how Russian literature served a vehicle of colonization, as well as why Ukrainians have been demolishing monuments to Russian poet Alexandr Pushkin.19

Demolition of monuments to Alexander Pushkin in Ukraine. Source: Kremenchuk City Council.

It was only after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine that the need to reevaluate what the west knows about Russia came to be taken seriously. Once it did, however, the scale of the discussion was impressive.20 That said, the push for this reevaluation came from Ukrainians like Lyubov Terekhova, who wrote about the need to decolonize the mysterious soul of Russian literature.21 It was only after Oksana Zabuzhko, one of the most influential Ukrainian writers, published “Reading Russian Literature after the Bucha Massacre” in The Times Literary Supplement, that Russian imperialism and the role of Russian culture became widely discussed by main western cultural outlets.22 And in January 2023, Elif Batuman, the author of several books about Russian literature, began re-evaluating her love of Russian classics.23 In this way, we can see how knowledge about Russia is being renovated in the west. One can only hope that such re-readings will be done in Russia and by Russian intellectuals, as well as spread beyond the west and move into the Global South.

The position of Ukraine today is also different from the India of Salman Rushdie or Homi Bhabha. When Rushdie wrote about the post-colonial subject who speaks with a forked tongue, without abandoning either a colonized or postcolonial Self but rather occupying those both spaces simultaneously,24 or when Bhabha wrote about the third space of enunciation that underlines the in-between-ness and hybridity of the postcolonial existence, their country was not in a war with its former metropole/colonizer.25 War de-composes the hybrid space. The postcolonial condition dramatically transforms in the context of war. Before 2014, one could speak about possibilities and potentialities of a “third space” or a “forked tongue,” in which Ukrainian identity included Soviet and post-Soviet traces simultaneously. Since 2014, however, Ukrainian society has been abandoning the space of hybridity and (re)building a new identity which fights its own space as well as the ability to speak in their own tongues on their own terms. This space is being built on the remains and the ruins left by the war. To return to Yakimchuk, she writes: “there’s no poetry about war/ just decomposition/ only letters remain/ and they all make a single sound – rrr.” The new space of existence is based on this sound, “rrr.” R as in resistance. R as in resilience. R as in rebuilding that continues amidst the war.

Lyuba Yakimchuk, “Decomposition,” trans. Oksana Maksymchuk and Max Rosochynsky. See ➝.

See more on this: Oksana Dudko, “A conceptual limbo of genocide: Russian rhetoric, mass atrocities in Ukraine, and the current definition’s limits,” Canadian Slavonic Papers 64:2-3 (2022): 133-145.

See ➝.

See ➝.

See ➝.

See ➝.

Mike Eckel, “How Long Could Ukraine Hold Out Against A New Russian Invasion?”, RadioFreeEurope RadioLiberty, December 17, 2021. See ➝.

Volodymyr Kulyk, “Discussions with Western Colleagues Over the Rumblings of the War,” Krytyka, no. 1–2 (April 2022).

Svitlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York: Basic Books, 2002).

One of the biggest fundraisers in Ukraine launched a campaign selling the bracelets with parts of the steel produced by the plant. All the money went to the needs of the Ukrainian military. See ➝.

See ➝.

There are also reports that Russians in Mariupol have demounted the monument to Holodomor (the man-made hunger under Stalin 1932-1933) and renamed one of the main alleys in the city from the Peace Prospect to the Lenin Prospect. By this, Russia is erasing the traces of Ukrainian identity in the city. See ➝.

See ➝.

Matthew Campbell, “Russia’s art raids in Ukraine are the biggest treasure loots since Nazis,” The Sunday Times, February 5, 2023. See ➝.

Yuliya Yurchuk, “Reordering of Meaningful Worlds: Memory of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army in Post-Soviet Ukraine,” Doctoral Thesis, (Stockholm University, 2014). See ➝.

Madina Tlostanova and Walter Mignolo, Learning to Unlearn: Decolonial Reflections from Eurasia and the Americas (Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 2012).

Vitaliy Chernetsky, Maping Post-Communist Cultures: Russia and Ukraine in the Context of Globalization (Montreal, Quebec and Kingston, Ontario: McGill-Queens University Press, 2007). Tamara Hundorova, Transytna kultura: Symptom Postkolonialnoii Travmy (Kyiv, 2013). Marco Pavlyshyn, Kanon ta iconostas (Kyiv, 1997).

Although the book is written with scholarly rigor, some readers have trouble accepting Thompson’s postcolonial critique, as she has in other contexts shown support of some right-wing policies of the Polish government. This case shows an important example of how postcolonial critique can be used and misused by different groups on different sides of the political spectrum to devalue postcolonial approach to the post-Soviet space. See ➝.

The Ukrainian Institute collected all published articles written about Ukraine and decolonization in 2022 and the list of those published in English counts more than forty. See ➝.

Lyubov Terekhova and Natalia Slipenko (trans.), “Decolonizing the Mysterious Soul of the Great Russian Novel,” Heinrich Böll Stiftung, March 29, 2022. See ➝.

Oksana Zabuzhko, “No guily people in the world?”, TLS, March 22, 2022. See ➝.

Elif Batuman, “Rereading Russian Classics in the Shadow of Ukraine War,” The New Yorker, January 23, 2023. See ➝.

Salman Rushdie, Shame (London: Vintage, 1995). See also: Samir Dayal, “The Liminalities of Nation and Gender: Salman Rushdie’s ‘Shame’,” The Journal of the Midwest Modern Language Association 31, no. 2 (1998): 39–62.

Fully recognizing Salman Rushdie’s life under constant threat of death since 1989 when Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, declared his novel, “The Satanic Verses,” blasphemous and issued a fatwa ordering the execution of its author I want to stress that I refer only to existential threat as a part of the nation. See one of the latest interviews with Rushdie published after the killing attempt of the author in August 12, 2022, ➝.

Reconstruction is a project by e-flux Architecture drawing from and elaborating on Ukrainian Hardcore: Learning from the Grassroots, the eighth annual Construction festival held in the Dnipro Center for Contemporary Culture on November 10–12, 2023 (2024), and “The Reconstruction of Ukraine: Ruination, Representation, Solidarity,” a symposium held on September 9–11, 2022 organized by Sofia Dyak, Marta Kuzma, and Michał Murawski, which brought together the Center for Urban History, Lviv; Center for Urban Studies, Kyiv; Kyiv National University of Construction and Architecture; Re-Start Ukraine; University College London; Urban Forms Center, Kharkiv; Yale University; and Visual Culture Research Center, Kyiv (2023).