Diego Marcon’s short films pair idiosyncratic approaches to animation with painful and provocative subject matter. In Monelle (2017) sleeping girls are tormented by ghoulish CGI figures amid the darkness of the old Fascist headquarters in Como. In The Parents’ Room (2021), a father, played by an actor wearing an emotionless mask, performs an opera about how he murdered his family. And in Fritz (2024) a computer-animated boy hangs from a noose, half-dead but still yodelling.

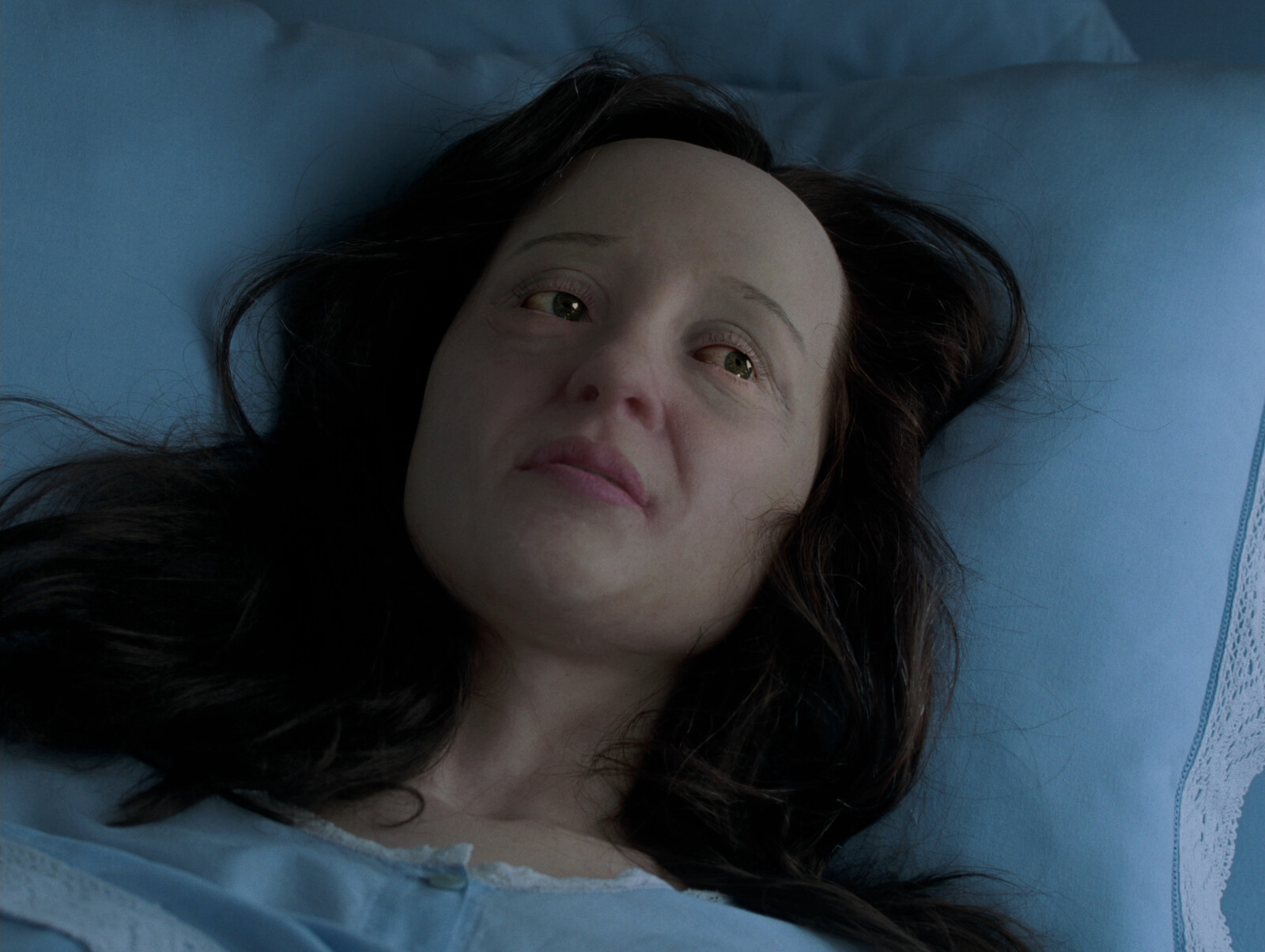

His new film, La Gola (2024), dramatizes an epistolary exchange between Gianni and Rossana, who are represented by hyper-realistic mannequins. The two characters appear in a series of close-ups, every time in a new outfit and location, as their letters are read in a voiceover backed by organ music. Gianni recounts the details of a recent feast, from a medieval soup served in an eggshell to Torta Fedora, a Sicilian cake covered in “mischievous ruffles” of “whipped ricotta,” which he calls “the bakeable Baroque!” Meanwhile, Rossana sends updates on her mother’s declining health, reporting an assortment of gruesome ailments including “flaccid little blisters” that ooze “syrupy fluid” and “diarrhoea accompanied by mucus.”

In this caricature of traditional gender dynamics, he indulges in unchecked consumption while she suffers under the weight of familial responsibility. “Good food,” Gianni reflects in a particularly inconsiderate moment, “eases the burden of dutiful social existence.” The difference between the pair is heightened to a farcical degree by the fact that they make no substantial reference to each other’s lives, launching at the start of every letter into their respective monologues. They sometimes sign off with “I miss you” or even “I long for a hug,” but this does little to alter the overwhelming tone of mutual self-absorption.

Like Gianni’s banquet, the film is an elaborate confection. The figures are motionless except for their expressive eyes, which are added using computer animation, and the sets—ordinary domestic scenes—are brought to life with a few dynamic details: raindrops on a window, branches in the wind, moonlight on distant waves. Two lifeless dolls, then, are ventriloquized by voiceover actors and vitalized by CGI as well as changing scenery and music. These elements do not cohere as they might in an immersive blockbuster. The voices were evidently recorded in a more intimate space than the organ, for example, and the moving parts stand out against otherwise static sets. Marcon is not concerned with suspending disbelief, preferring to stress what he calls the film’s “thingness.” And yet, despite its explicit artifice, La Gola still produces a visceral impact, through its comic timing, endearing characters, and grisly details. We still laugh at Gianni’s selfishness, our mouths water as he recalls each course, and we are still repulsed, and even saddened, by Rossana’s tale of woe.

In the final letter, Rossana describes her mother lining up prized possessions, resigned to her fate and “packing to go.” Although her eyes are watery throughout, this is the only time a tear falls, but the droplet disappears as it leaves the CGI portion of her face. Typical of Marcon’s sensibility, in a single movement the tear both marks the film’s emotional climax and betrays its technical trickery. With such details, La Gola upholds a tension between constructed “thingness” and psychological impact, generating in the viewer a strange mix of bodily affect and critical awareness of the image’s falsehood. In this way, the film satirizes the blunt manipulative tactics of popular entertainment.

What makes Marcon’s work dumbfounding, though, is that it does not point us to a reality beyond illusion but rather delights in artifice. It turns us all into Gianni—the saint of cinematic experience—escaping social burden into a realm of sensuous pleasure. The installation of La Gola at the Kunsthalle Wien, in a cavernous gallery with just a small central island of theatre seats, evokes the escapism and solitude of cinema-going, and the film presents a hermetic world of finely wrought surfaces: rarefied allusions, complicated technologies, meticulously crafted melodies and words. Its script is a web of aesthetic resemblances in which art, cuisine, and illness become entangled. In a strained attempt to convey the skill of his cook, for example, Gianni quotes a critic who compares the work of one “great artist” to “a slow, steady irrigation of the rice paddies of painting.” Two minutes later, Rossana describes diarrhoea so thin it looks like “rice water.” The “natural”— exemplified here by rice paddies and bowel movements—is pushed away by metaphor, becoming itself a cultural artifact, an image among images.

Marcon’s films are defined at the level of form by a negation of naturalism and at the level of content by social decay: broken communication, disease, child suicide, wife murder. Despite my neat separation of these features into “form” and “content”—itself a naturalist assumption, whereby subject would precede technique—it is difficult not to understand them as causally related. Crucially, Marcon’s subjects (heteronormative relationships, the nuclear family, fascist politics) have achieved supremacy through claims to the natural. His films, camp and macabre, celebrate artifice as a way of rejecting ideological naturalization, and this process is somehow responsible for the work’s darkness, its sense of fragmentation, cruelty, distress. It is as if, once stripped of their natural status, reactionary structures collapse under the weight of their own monstrous deformities. Some stark truths, it seems, only appear in twisted illusions.