Imagine a historical juncture when machines promised to annex much tedious labor, manual or mental; to gather and strew the vast array of human knowledge at speeds and scale not dreamed of in our present technology; to pilot our imaginations towards new form and content in the arts, even new emotions and sensations. And at the same time threaten to steal our jobs and loot our private lives, tell us lies and fill our world with futuristic kitsch or inhuman austerity. Imagine if certain grim technicians enriched and refashioned themselves as prophets of this transmutation. And so on—the time of course is our own and not. It might be the post-WWII rise of techno-rationalism and information, the thrill of personal computing in the early 1980s, internet boosterism a decade later, the present perplex of competing perspectives on AI. Or the mid-nineteenth century, with its steam trains, telegraphs, and offset printing presses. In a crude history of modernity, the bourgeoisie is always rising, and technology the ambivalent object of faith and foreboding.

In other words, “Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet”—a survey that runs from the 1950s to the early 1990s, and commendably foregrounds artists and movements from Latin America and Eastern Europe—does not actually seem to describe a period that was notably anxious or excited about technology. Not compared for example with the Industrial Revolution or the First and Second World Wars. But it was shadowed and brightened by a sense that postwar developments in computing not only altered aspects (military, medical, mercantile) of contemporary life, but were precursors of something much more transformative: the world of instant communication, ubiquitous surveillance, and intelligent machines in which we now live. (Walter Benjamin: “Each epoch dreams the one to follow.”) In that sense, the exhibition circumscribes a period in which ideas, visions, or makeshift models of things to come were as much part of artists’ responses to the information era as was their deployment of the technology itself.

The first striking thing about the work in “Electric Dreams” is how much of it is solid, physically insistent, handmade or drawn, not dramatically departing, in material or form or modes of display, from mid-century conventions in painting and sculpture. In the context of this show, some of the early works can appear quaintly mechanical instead of digital. But they appeal to an idea of the programmed machine.

Jean Tinguely’s “metamatic” and “metamechanical” works of the 1950s—represented at Tate by his Metamechanical Sculpture with Tripod (1954)—twirl and nod according to the speed and force of their motors, and already suggest later works of Tinguely’s that slowly destroyed themselves. Atsuko Tanaka’s Electric Dress (1956)—shown here in photographs and drawings— is a lethal-looking snarl of cables and coloured lightbulbs inside which the artist resembled an ungainly cyborg. A decade later, Takis’s Elecro-Magnetic Music (1966) uses an electromagnet to make a needle twitch and clang against a wire, amplified: a simple but absorbing enchantment of on-off binary logic. Such works relate to the most advanced informational systems through a kind of primitive metonymy: the crude circuit stands in for the unimaginable and unavailable complexities of the new tech sublime. Unavailable, that is, to most artists: the exhibition also covers the heyday of artistic involvement with research institutions such as MIT, whose Center for Advanced Visual Studies hosted sculptor Wen-Ying Tsai at the end of the 1960s—the strobes and vibrating rods of his “cybernetic sculptures” are awoken by the viewer’s presence.

In fact, a good deal of the art in “Electric Dreams” embodies aspects of technology that for the artists in question could only remain conceptual, imagined or figural. From circuit to diagram to program to network: these innovations, which are also cultural fantasies and formal temptations, inform a lot of the work from the 1960s. Although groups such as New Tendencies in Zagreb might have distanced themselves from the geometries and hues of Op Art, and the work itself derived from machinic logics and patterns, there is a strong tendency towards geometric abstraction. In Günther Uecker’s relief White Field (1964), bristling white nails cast shadows and appear to move with the viewer’s shifting perspective. Marina Apollonio’s Circular Dynamics 6S+S II (1968–70) is a dizzying mathematical sequence of concentric circles, which the Italian artist also imagined as a “kinetic activation space” on which spectators might move. The effect is, in the end, to sidestep the guiding metaphors (or determining systems and algorithms) of computing to produce a less defined space or medium—a near-uniform but mobile field, not yet a network.

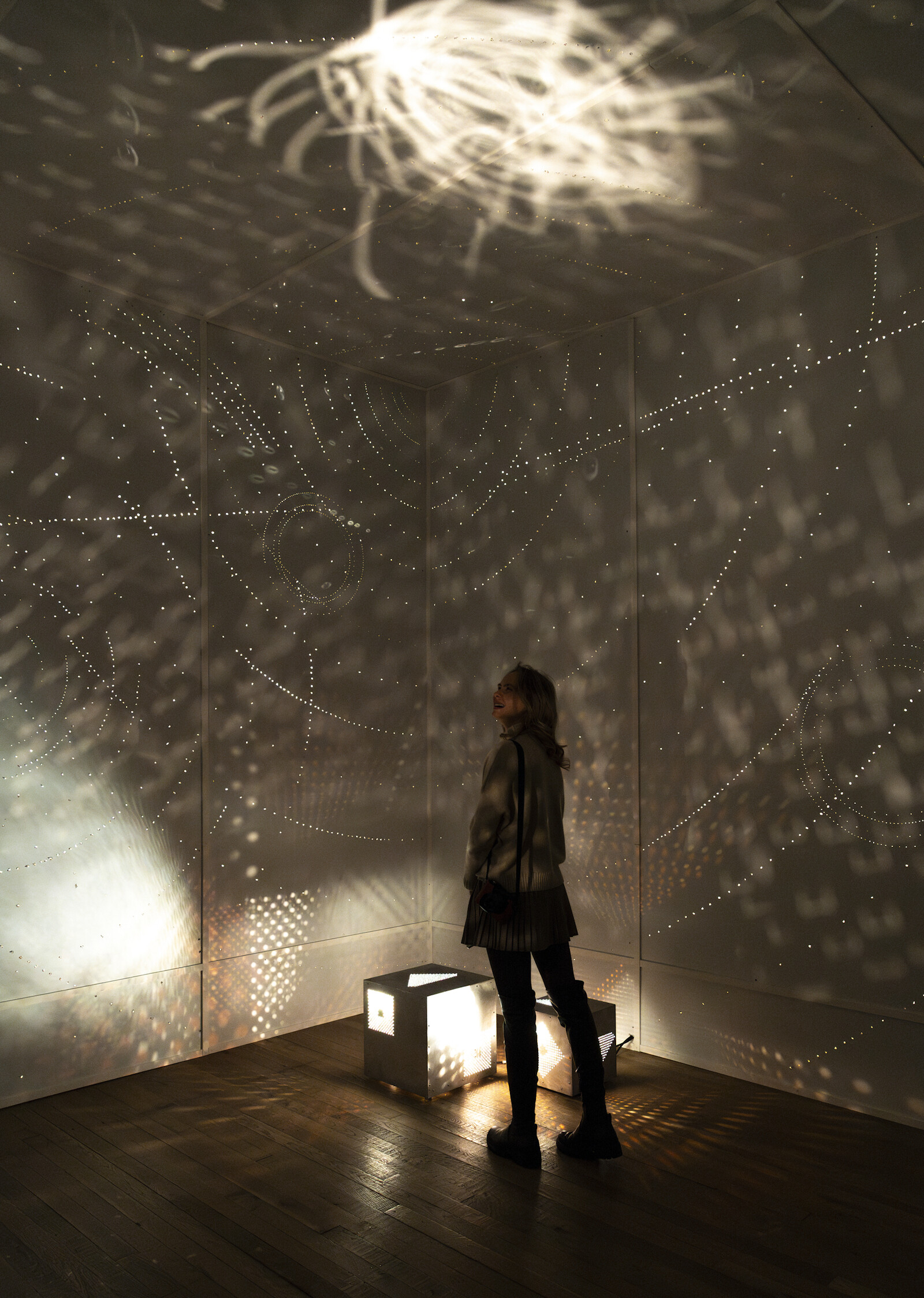

More or less spectacularly departing from these relics (despite themselves) of mid-century abstraction, are the works of the Dusseldorf-based Zero group. At Tate Modern, Otto Piene’s “light ballets” are represented by Light Room (Jena) (exhibited 2007): a darkened room in which points of light perform a subtly enveloping dance. By contrast: in 1968 Piene collaborated with Aldo Tambellini to produce for German television Black Gate Cologne: a pummelling piece of black-and-white psychedelia featuring inflatable sculptures and five-way video superimpositions. Oddly, it’s one of the few places in “Electric Dreams” where you feel the future being canvassed alongside machines might be truly giddying and unmooring.

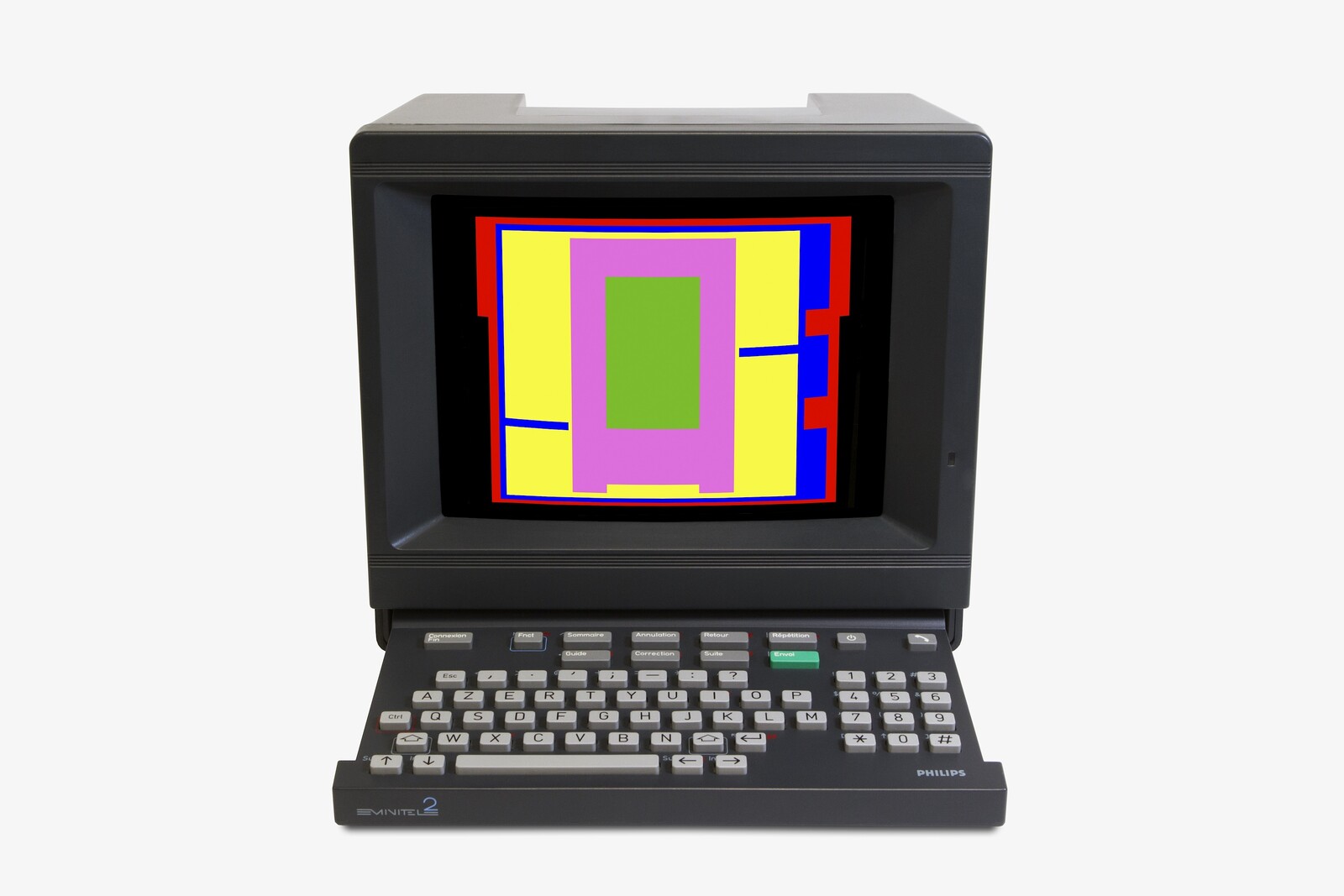

The exhibition shares a title with a forgettable 1984 film about a sentient home computer, but more resonantly recalls a hit song from its soundtrack. “Together in Electric Dreams,” by Phil Oakey and Giorgio Moroder, was already a belated, nostalgic reminder of the genuine pop futurism both artists had pursued just a few years earlier. The metaphoric potential of new technology quickly fades when it occupies your office cubicle or sits on your kitchen counter. It then becomes a tool to be used and misused, as in Eduardo Kac’s poetic and brazen repurposing of the Brazilian version of the French Minitel network of domestic terminals, or Suzanne Treister’s roughly pixelated Fictional Videogame Stills (1991–92). Works like these, from the last decade or so of pre-internet art, feel as if made in a more innocent world before anxiety and zeal arrived again.