Humans became human by representing themselves and others. By painting images on cave walls of animals that mimicked those they chased, early humans produced the imaginaries and traditions that define us as a species. With their drawings, they invented past and future and connected memory to desire, remembrance to anticipation, trauma to anxiety. The images on those walls might be still, but the stories they told were in motion, animated by the light cast by flickering fires.1 As such, it could be said that the history of cinema predates written history. Cinema emerged from the animals whose images, engraved in their own blood and hair, expressed motion through time and space, and moved their audiences.

This awareness of the archaic nature of cinema, and its relationship to nature, is at the base of Gabriel Chaile’s memorable installation Selva Tucumana [Tucumán Jungle] (2024), which signals an important change in his artistic vocabulary away from the large-scale adobe figures for which he is best known. Born in San Miguel de Tucumán in 1985, the Lisbon-based artist has often sought inspiration in land and kin. His characteristic anthropomorphic sculptures—whose aesthetics echo the precolonial creations of his birthplace—are both private and public. Connected to the past and actualized in the present, these impressive clay constructions reference his personal life (most of them bear the names of family and friends) while also functioning as wood-fired ovens around which people can gather to participate in and observe the communal rituals of food-preparation and togetherness.

“Los jóvenes olvidaron sus canciones o Tierra de Fuego” [The youth forgot their song or Land of Fire] marks a significant evolution in the artist’s practice, revising his trademark forms and expanding his investigation into sculptural space. For his 2023 exhibition “Usos y costumbres” [Customs and habits] at Studio Voltaire, London, he covered the walls of the former Victorian chapel with clay. Here, he responds to the old premises of Deko Behrendt, an iconic party decoration and mask shop in Schöneberg. It feels fitting that a place historically associated with festive disguise and queer community building is transformed into a pre/trans/post-human cinema.

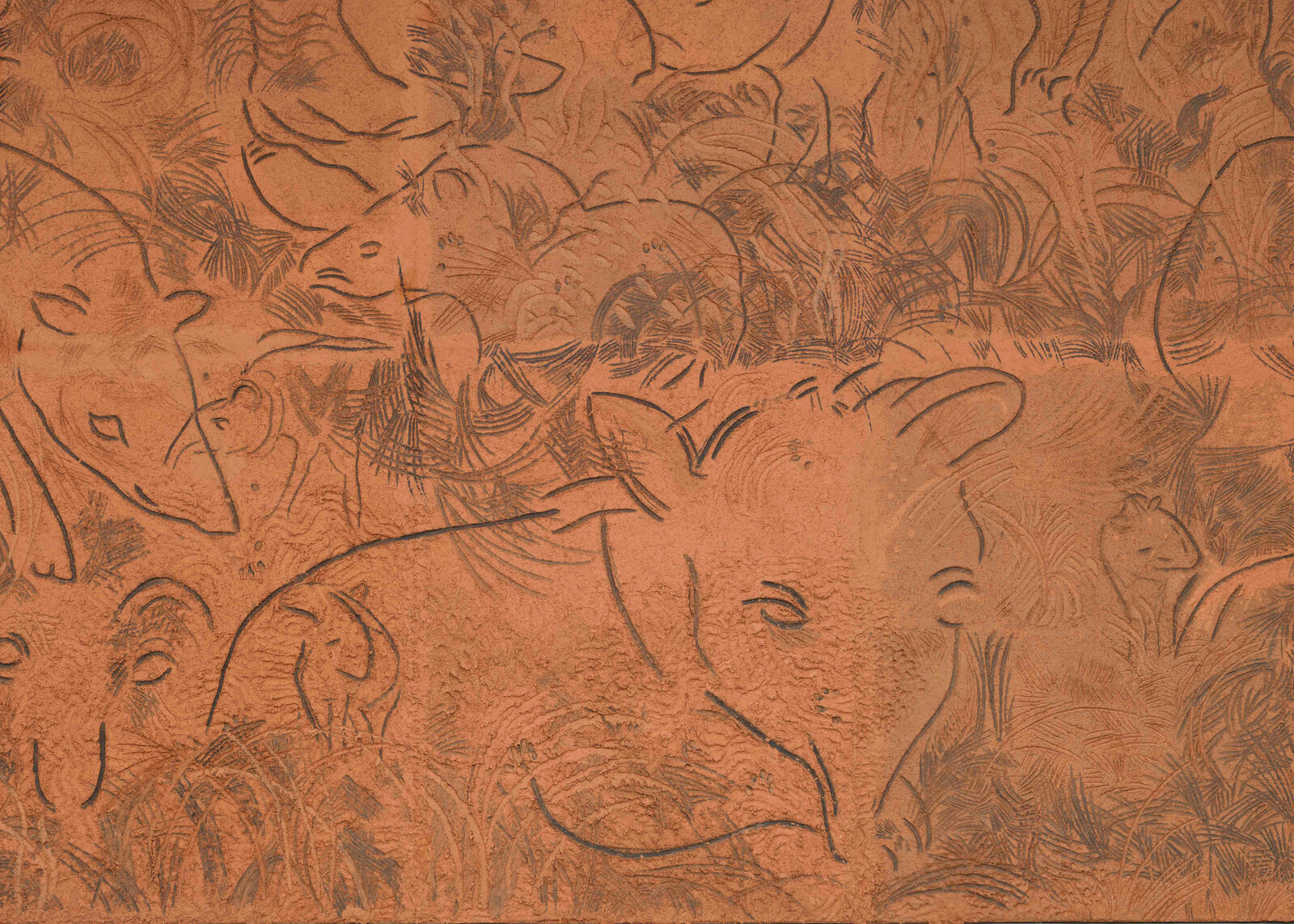

In this cinema, the audience face an eight-meter-wide adobe mural on which overlapping charcoal drawings of tapirs have been etched. There are full-body representations of the charismatic animals native to South America and South Asia—some so large that they contain smaller tapirs within them—and figurations of their heads or profiles. Nonetheless it is clear that this is a group, a clan, a rowdy ensemble, and not a single tapir drawn many times. Plants and vegetation are minimally represented by lines that grant movement, ground, and depth to the multiplicity of animals. Two large tapirs, outlined in welded steel, detach themselves from the group and project their shadows onto the screen, generating a three-dimensional experience of this film in mud and clay.

While Chaile’s familiar semi-figurative sculptures have a penetrating gaze, these tapirs have no irises. The void of their empty eyes seems to point towards the species’ extinction, and this allusion is consistent with his entire oeuvre’s address to the decimation of Indigenous life. Filling the room, an audio piece in English and Spanish relates the myth of two baby tapirs who came down from the sky and slowly metamorphized into humans while terraforming their forests through fire and wit. While the childish imaginary of the mural and story is tainted by sadness—yet another tale of human disaster—this new cinema also brings hope, suggesting the possibility of reimaging humanity’s place in the world through storytelling and dreaming. We might recognize ourselves as kin to the tapir, attempting to rebuild our identities based on respect and honor for those with whom we share the world.

See Brian Handwerk, “Ice Age Artists May Have Used Firelight to Animate Carvings,” Smithsonian Magazine (April 22, 2022), https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/ice-age-artists-may-have-used-firelight-to-animate-carvings-180979943/.