“Do you love me, even though I’m sometimes irritating and a little bit selfish?” Miranda July asks in the brief audio recording The Crowd (2004). I wasn’t sure. I had spent nearly three hours in July’s solo exhibition at Fondazione Prada’s Osservatorio—the first major retrospective of her performance and visual art—and I was getting tired. Her voice echoed off the walls of the bathroom where the piece had been installed.

“That’s a good thing, because I love you too. I’m just not very good at it! But I’m trying to change,” she responds. A recorded audience cheers. “This song is for you and it’s a love song,” July concludes, her voice fading to the sounds of a band tuning up. As I washed and dried my hands, I warmed back up at the cheerful resolution. As though anticipating my grumpiness, the artist had assured me of her affection.

The Crowd is a succinct example of July’s signature performance move: vulnerability, bordering on neurosis, giving way to sentimental declarations that secure her power.1 She has a gift for connecting with an audience, cutting through the noise of a large group to create intimacy with individuals. Organized by Mia Locks, “New Society” showcases the two major threads in her work, sometimes at cross purposes: staged confessional moments in her own voice, and the creation of space for anyone to become a collaborator.

Taking advantage of July’s extensive archive, the show positions her foremost as a performance artist. The lower floor, which features ephemera dating from 1996 to 2015, includes early videos and full-length documentation of theater pieces. In the short film The Amateurist (1997), July plays both a barely comprehensible “professional” number-cruncher and an “amateur” striptease version of herself, trapped inside a black-and-white TV. Nodding to the history of performance art and July’s former real-life side hustle as a peep show dancer, The Amateurist renders unstable the hierarchy of voice and movement, subject and object. July was in her mid-twenties when she made the film, but the themes of embodiment, watching, and desire inform her work to this day. Dance in particular has returned in her recent practice, made strange, once again, as a form of longing.

Raised in the Bay Area by parents who were writers and founded the independent press North Atlantic Books, she became a performer and teenage zinester (Snarla, her series with Johanna Fateman, was recently included in the Brooklyn Museum’s sprawling zine exhibition “Copy Machine Manifestos”). While still in high school, she wrote and directed a play, The Lifers (1992), based on her penpal relationship with a man incarcerated for murder. Later in the 1990s, she found her footing in the Pacific Northwest DIY queer feminist punk scene. There, she initiated the feminist video art “chain letter” service Big Miss Moviola (aka Joanie 4 Jackie), compiling and distributing collections of short films submitted by women artists.

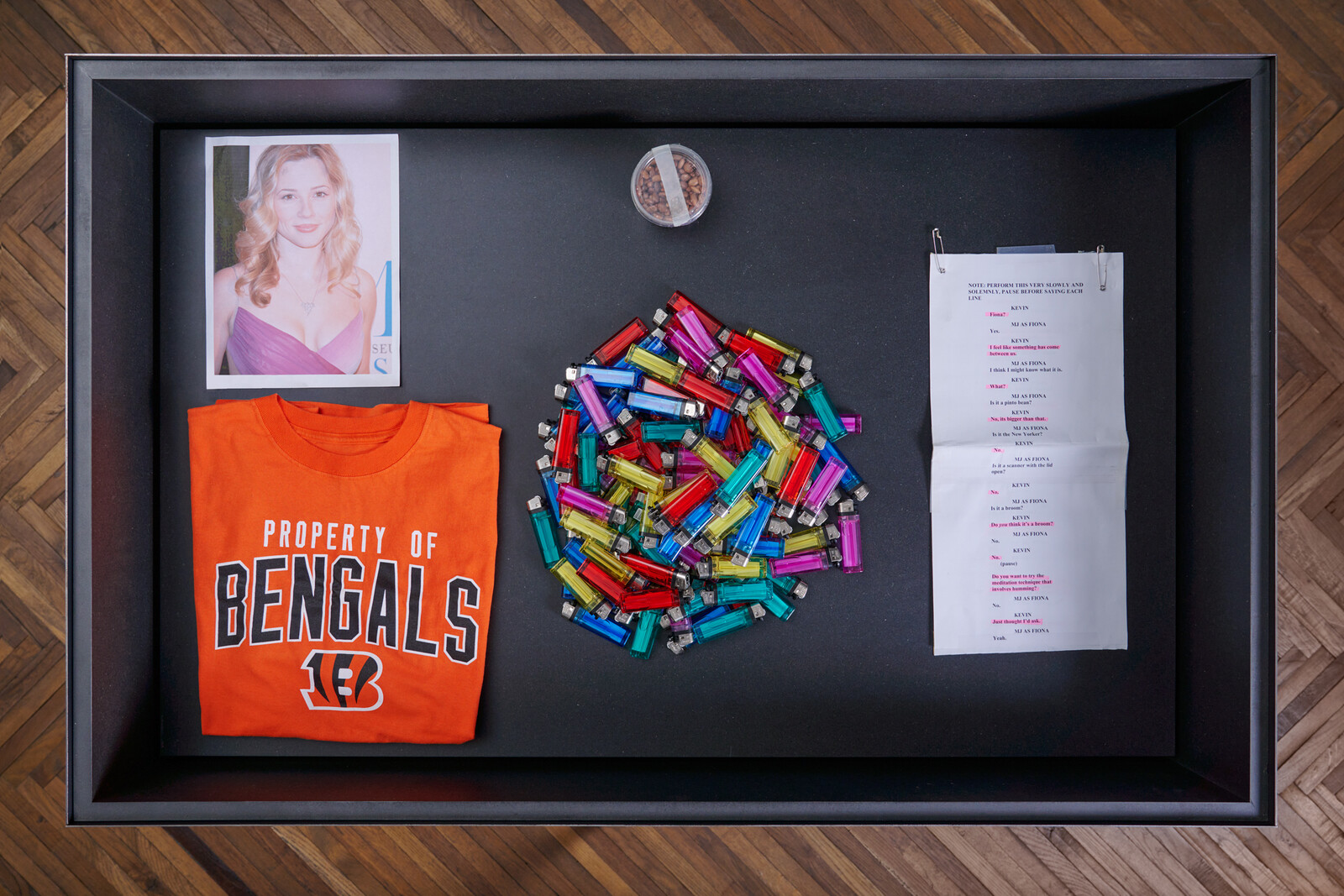

She also performed surreal monologues at punk clubs that evolved into multi-character, one-woman shows such as Love Diamond (1998)—screened in its entirety here, as are all the other theater works mentioned. Combining projections with tightly scripted content, July plays the parts of an awkward teen, her overbearing mother, a pontificating doctor, and a mysterious spiritual entity. At several points in the production, she enlisted audience volunteers to read “narrator” lines that she communicated offstage, via an old-fashioned earpiece. Things We Don’t Understand and Definitely Are Not Going to Talk About (2006) was staged a year after her first feature film release. This work sees her experimenting with audience improvisation. She confidently cast three audience members to play its main parts: Fiona and Donnie—a couple breaking up—and Fiona’s new paramour, Kevin. The remaining spectators form a Greek chorus who periodically contribute in unison. Throughout the show, July plays all three parts alongside her audience-participants, dressed in identical costumes.

Mia Locks, the exhibition’s curator, notes the tension in July’s double-casting decision in her catalog essay: “She is trying to relinquish control but also, maybe unknowingly, showing us her own struggle at the same time.”2 July asks for help in staging her production, but what she really seeks is emotional investment while maintaining directorial authorship. In New Society (2015), July takes the bid for sympathy further. She feigns forgetting her lines before corralling her audience-participants into organizing a semi-scripted, off-grid civilization. “Now we had all the time in the world for our feelings,” she tells her new comrades, overseeing their creation of a flag and constitution as the community experiences births, deaths, and its eventual dissolution.

The upper floor showcases projects in which July exchanges authorship—with a telemarketer, a Nigerian Uber driver, and other relative strangers—via emerging technology. Learning to Love You More (2000–07), a set of Fluxus-like instructions for the digital age that July conceived with Harrell Fletcher, invited people to submit photos and videos online. July has here restaged one assignment in the series (“Make an exhibition of the art in your parents’ house”) in analogue. Miriam Goi, a young Italian artist raised in the outskirts of Milan, has assembled a collection of art and knick-knacks owned by her mother. Learning to Love You More is moving for its simplicity and creative generosity: it shows that art can be made from anything, a lesson that can be passed down over time. Indeed July’s best works either relinquish control entirely or drill down in their specificity, with all its messy, intersectional complications.

In her most recent video series, F.A.M.I.L.Y. (Falling Apart Meanwhile I Love You) (2024), July uses the cutout tool on the iPhone camera to dance “duets” with participants she solicits online.3 The dancers wear either underwear or drape themselves in bedsheets, per July’s directions. She makes the content weirder and/or sexier by adding her stockinged form, alongside her collaborators, in ghostly embraces. The clunky technology contributes another level of sculptural strangeness, sometimes replacing a limb with a flickering background. The series—at times uncomfortable to watch—shows July approaching a new form of thwarted connection. She has jettisoned her former bid for intimacy via vulnerable confession, laying bare her desire more starkly. That kind of connection, this ongoing piece suggests, is hungry and sometimes awkward. At the same time, July appears to have found a new peace with herself in it. If her audience finds it irritating or selfish, she no longer seems to care.

“Vulnerability is like a starting place, for anything that might be new. And it’s such a relief when you realise that there’s something you can let go of. But – vulnerability isn’t, in fact, that vulnerable. It’s … power.” Miranda July, quoted in Eva Wiseman, “ ‘I was in kind of an ecstatic freefall’: Artist Miranda July on writing the book that could change your life,” The Guardian, (May 12, 2024), https://www.theguardian.com/film/article/2024/may/12/i-was-in-a-kind-of-ecstatic-freefall-artist-miranda-july-on-writing-the-book-that-could-change-your-life.

Mia Locks, “Willful Women: On the Art of Miranda July,” in Miranda July: New Society, Quaderno Fondazione Prada #37 (Milan: Fondazione Prada, 2024), 13–14.

In her new autofictional novel, All Fours, dance plays a central role. July’s protagonist begins an unlikely liaison with a Hertz employee/hip-hop dancer, and subsequently reimagines her marriage and living situation. As she was writing, July’s marriage also dissolved in real life. The acronym F.A.M.I.L.Y. (Falling Apart Meanwhile I Love You) nods to the potential of domestic and erotic reconfiguration.