Gregg Bordowitz has been writing, publishing, performing, and teaching consistently and prolifically since the early nineties in New York, making “agitprop” videos as an AIDS activist and member of ACT UP. Though his material output is slim, his wordcount is substantial. Rather than focus on the early activist works for which he is best known, this exhibition concentrates on writing as the core of his artistic practice, but also as a daily habit—“writing as an activity of thought,” as Kunstverein Director Fatima Hellberg puts it—that becomes material testament to his ongoing presence, as a long-time survivor of HIV.

To create an exhibition from this ephemeral practice is audacious, particularly in the Kunstverein’s cavernous former flower market hall, but Hellberg has a track record of conjuring shows from unruly or nebulous bodies of work (David Medalla’s 2021 retrospective, for example, or the large-scale solo exhibition of Georgian artist Tolia Astakhishvili in 2023). In the absence of discrete objects, the exhibition relies on subtle gestures, the first of which is a narrow red line affixed to the wall, three inches from the floor, that follows the entire perimeter of the exhibition space. It establishes intention and constructs a kind of “holding environment,” to borrow the term of psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott. It is also, literally, a roter Faden, or “red thread,” the German term for “common thread.”

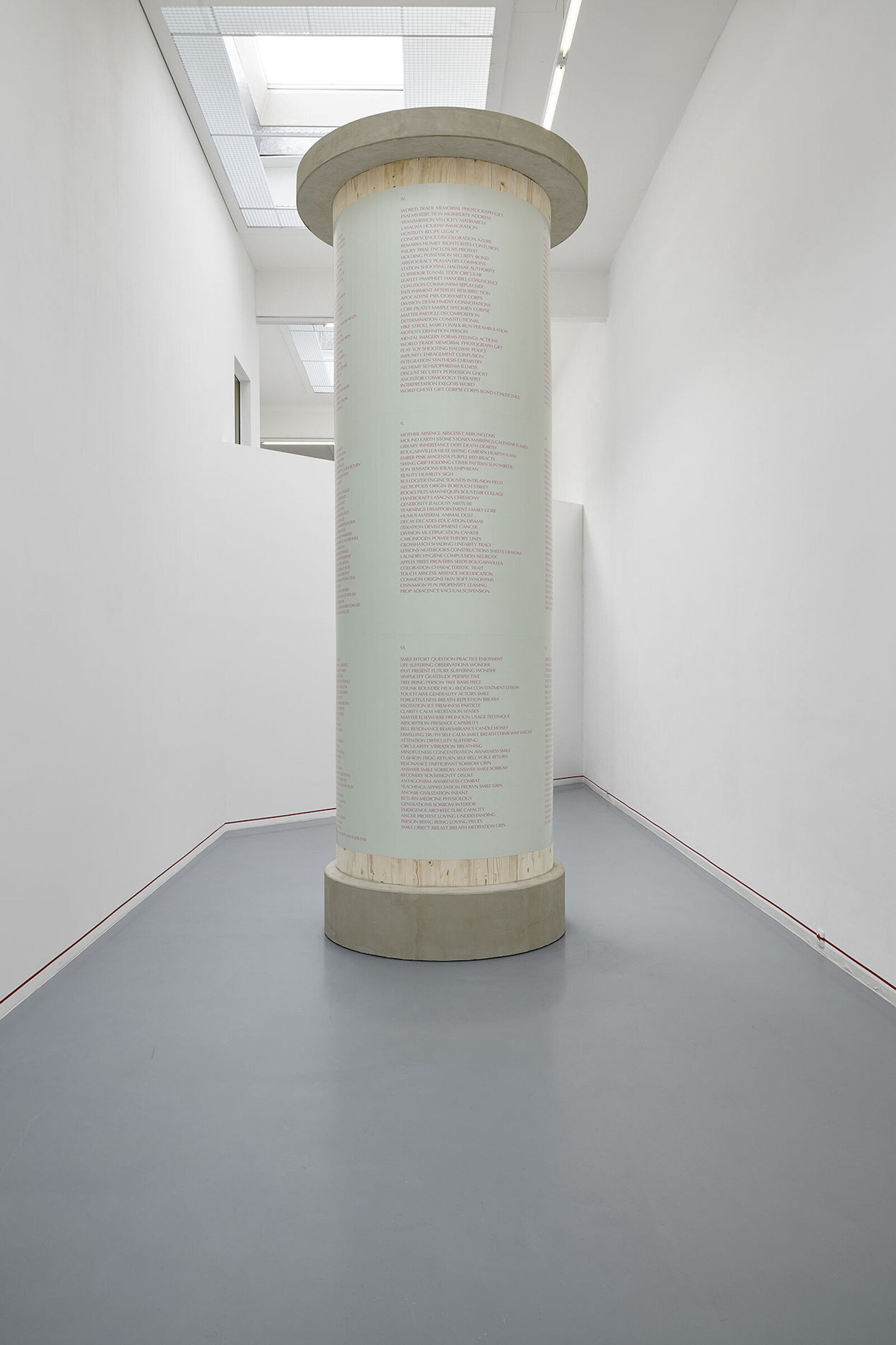

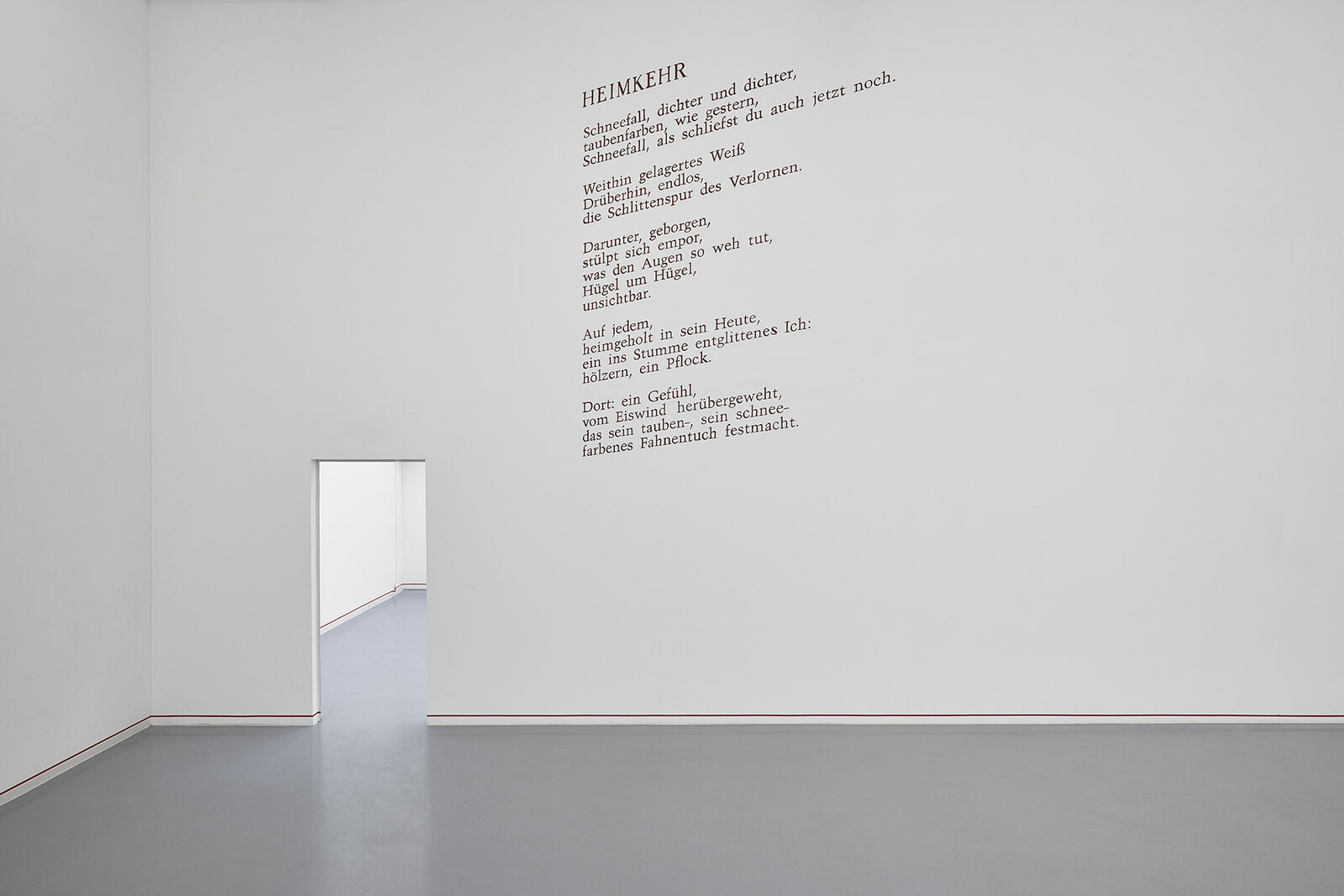

Several canny architectural interventions, not in fact devised by Bordowitz but left over from Michael Kleine’s exhibition last year, articulate a surprising spatial dramaturgy. Inverting the usual entranceway, we are led instead around the back, arriving in a large open space something like an indoor public plaza. It is furnished with a few simple objects, more prop than sculpture: a white-painted bench, a low brown stage, a large advertising column like those found on German streets, and a gathering of rudimentary cloud-like forms affixed to one wall. Sparse and indefinite, it suggests a space for thought. Here also are the show’s first words, not Bordowitz’s own but Paul Celan’s, whose poem Heimkehr (1955) is painted, slanting, on the wall. The slant suggests that our angle on language—or history, or art—is key to meaning. Subjective perception intersects with words (or art, or experience) to create something new.

In the plaza, the mumble of speech from nearby videos seeps in. The centerpiece of the exhibition is a compilation of extracts from several existing works, projected large scale in a central enclosed room. Five acts, from 2012 until now, compose what Bordowitz calls an “autobiographical documentary,” each offering a different format of the spoken word—comedic stand-up, lecture, sermon, poetry reading, song—and each a different version of the artist. The compilation is lengthy (eighty minutes in total) so I watched it in parts, popping in and out on my way to and from other areas of the show, catching snatches of Bordowitz in a bright red suit and striped shirt reading his long elliptical poem “There: A Feeling,” its title borrowed from Celan. Or Bordowitz slick in grey, performing a deadpan rendition of his childhood in Queens, growing up as a third-generation Yiddish-speaking Eastern-European Jew, and a “faygeleh” at that. In another extract, he is delivering the Yom Kippur sermon in yarmulka and prayer shawl, talking about divine inspiration, the word of God, and Judaism as “an ongoing conversation”. In another, he wears a patchwork pullover and ruminates on his long-held belief that “art can change the world.”

Taken together, these episodes construe a meditation on heritage, faith, gratitude, and forgiveness, weaving the various aspects of the artist’s life as a self-described “New York Jew pinko queer with AIDS” back into its original fabric. They are interspliced with a brief, disarming piece of iPhone footage: a frail old man in a hospital bed, eyes closed, breathing the death rattle of his final hours. Though hard to watch, this evidence of the end of a life becomes a kind of punctuation. Death and life are back-to-back. The natural end of an elderly man in the presence of his family could also be a symbol of hope, or defiance, even.

The artist appears as a many-sided entity, but in each instance, his charismatic presence and command of language’s nuance hold the camera’s, and audience’s, attention. As the original audience of each piece is not pictured, we become their substitutes. Only at the show’s opening, when Bordowitz gave a speech on the low stage in the plaza area, announcing his intention to “speak off the top of his head”, were we the original audience. Elsewhere in the exhibition, serial monoprints picture tangled, sometimes letter-like motifs. Another advertising column is plastered with a many-part poem consisting entirely of nouns, which butt up against each other, proving hard to read without any verbs, prepositions or adjectives to loosen them into sense. In the final room is the show’s only early work, the video Portraits of People living with HIV (1993).

In this sparse and at times oblique exhibition, ideas emerge between works, which often appear partial or provisional. The last section of the large-scale projection seems to state the case most directly. To footage of a lush fig tree and the accompaniment of a simple melody, a voice sings a song of gratitude, repeating the words “This is the fast I want.” Borrowing text from Isaiah 58, Bordowitz’s chosen “fast” or sacrifice is that his body is able to mend itself, despite the string of health difficulties resulting from his daily medication. In the end, he is still alive. The song’s final words, also from Isaiah, are belted out: “Cry out, don’t hold back, Raise your voice like a shofar.” This is a battle cry, an anthem to live your life by, and this is where agency lies: in words expressed, on the page, in your mouth.

In linking his life as an artist so directly to his faith Bordowitz emphasizes his claim that “Jewish identity is the template through which I understand my other identities”. This identity is rooted in the “Yinglish”, or Yiddish-English, he spoke at home as a kid, rather than fixed practices or ideology. As he said in his opening night speech: “This stage is home. Language is home. I am diasporous.” Diaspora is also a form of survival, an alternative to the Jewish nation-state. The current deadly conflict seems to exist in this show as absence, as if this is where the limitations of language become palpable. Instead the baton is passed to Paul Celan, Holocaust survivor, to find words that can speak to atrocity.