If each generation gets the drug it deserves, it also deals its own communicative form. Ours is the generation of the fragment, the snapshot, the caption, the info-bite: dulled post-digital distortions of the pictorial and literary chop-ups that appeared in the interwar years, via George Grosz, Hannah Hoch, and Walter Benjamin. Bertolt Brecht explored the form in a dramaturgy that poked at a public unresponsive to the rise of totalitarianism. Featuring material that is now a century old, “brecht: fragments” provides a masterclass for understanding how cropped photographs and scraps of text might amount to more than social media gruel and instead, artfully combined, result in riotous dramatic forms, crisp counterpropaganda, and pertinent anti-capitalist critique.

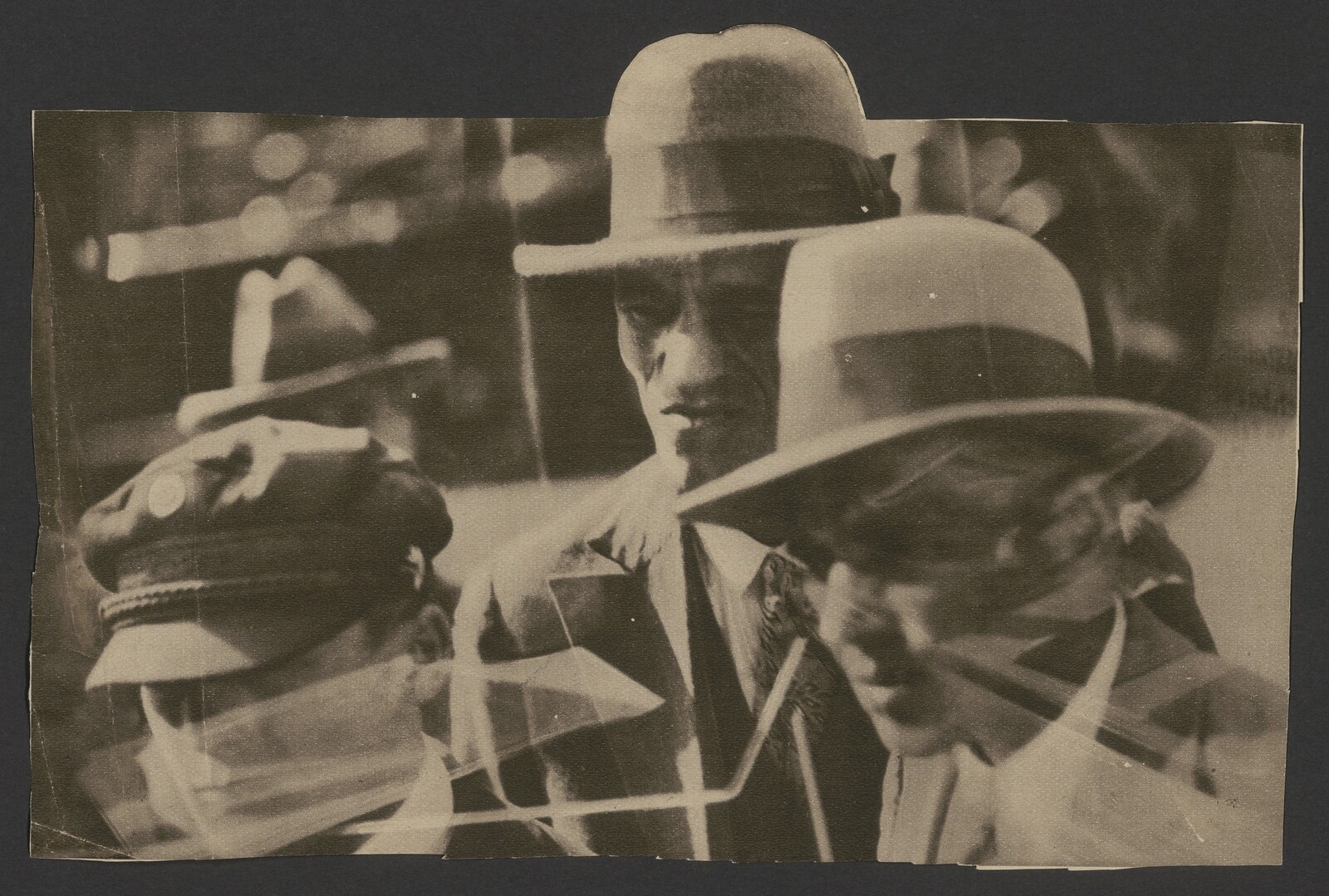

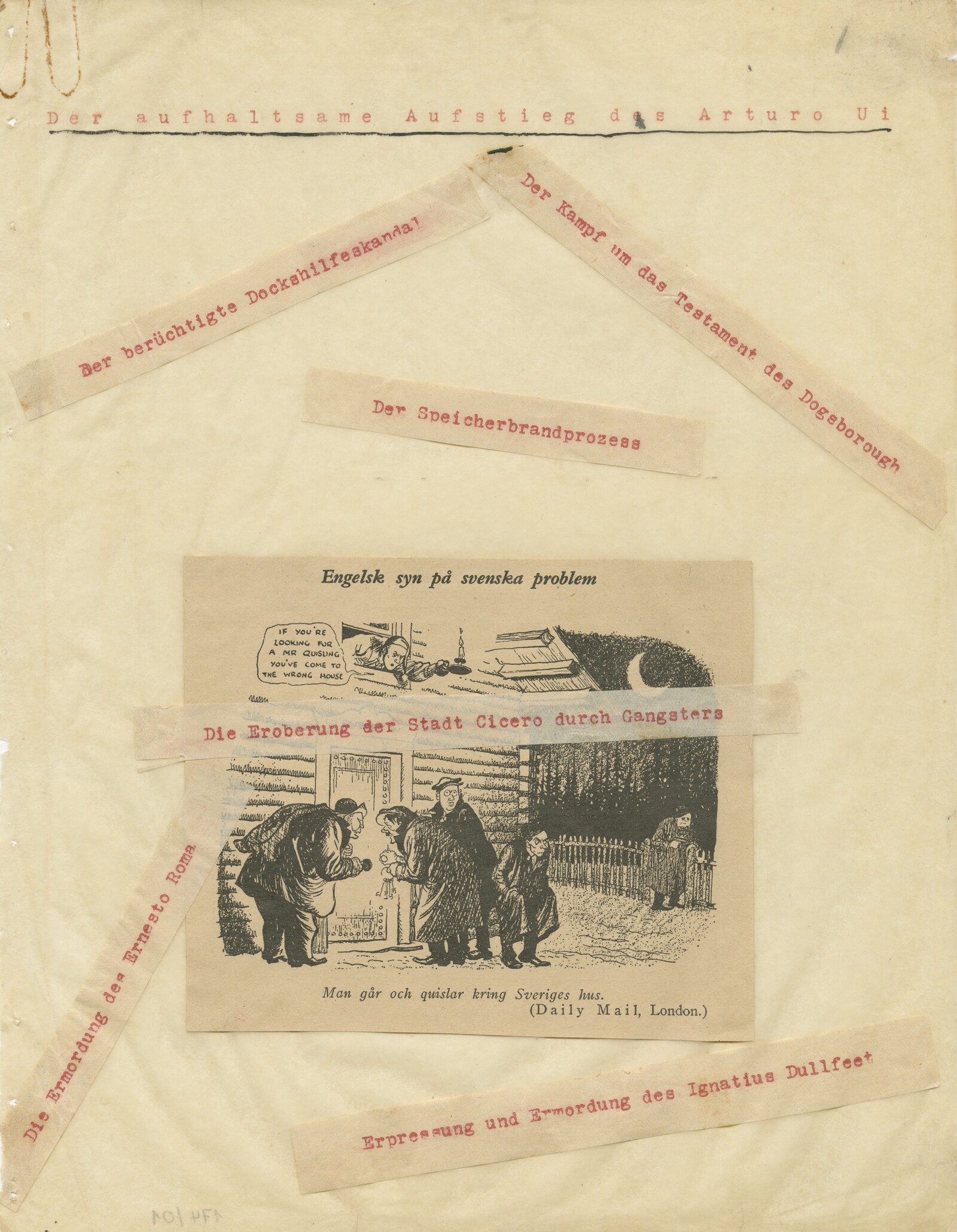

The exhibition is divided into two parts. The first includes a selection of paper elements from the Bertolt Brecht Archive (of its total of 200,000 folios) at the Akademie der Künste, Berlin, displayed in climate-controlled vitrines or copied and pasted across the walls and other props. A set of never-displayed collages (BBA 1198, 1941-47) shows how Brecht clipped original German press photographs and stuck them to paper in pairs and trios to explore images of social formations, urban gatherings, couplings and trysts, and the male leaders who motivated or alienated those they ruled. Corresponding to these gestural studies, alongside other scripts, collages, notebooks, and ephemera, the exhibition hosts a performance element, staged twice daily for most of the exhibition’s run.

By the time I attend it is booked out and there’s frenetic energy at the door, with fragment-junkies jostling for ticket returns. Those who make the final cut spill into the rear ground floor of Raven Row’s three-storey Georgian townhouse where, as an audience of thirty-six, we listen to a prologue. The group is then halved, with one cohort staying put while the other (mine) is led away. We follow a promenade piece that has been assembled from four of Brecht’s performance fragments: Fleischhacker (1924–31), The Flood (1926–27), Fatzer (1926–30) and The Breadshop (1929–30). It is delivered by a ten-strong cast, each playing up to five roles, reshuffling as each fragment demands. In the entrance hall, a jubilant four-piece Savannah family (from Fleischhacker) performs a ditty about their great misfortune, with guitars and banjos. Fleischhacker himself slices through this perplexing scene and leads us up the stairs with a bracing soliloquy about fortune-seeking. At the top, he disappears through a door, and a Prophet Nahaya appears (from The Flood) to predict the end of the world. And so, the uproarious mix continues, each new reconfiguration facilitated by interconnecting rooms and doors. Separate staircases allow actors escape routes and re-entries which enable them to perform the run for us and for the other group in reverse order. The wizardly set-up articulates both the structural logic of Brecht’s Epic Theatre—made of literary units that are chopped, respliced, multi-climactic, and anti-durational—and how inventively it might be spatially produced in the present.

These fragments, though not formally connected, are in tune with one another, given they were all conceived during a period of tremendous experimentalism, before Brecht’s exile (he left Germany in 1933), when his mistrust of capitalism, futures trading, market inflation, and the Great Crash of 1929 turned him towards Marxism and away from classical drama. He didn’t want to write a relatable hero, a plot with a singular tension or neat resolve. He wanted things broken up, dicey, more tradable and duplicitous, to represent a Western order governed by financial capitalism at one end and poverty and subjection at the other, with inequality and volatility masked by strategic disinformation (newspapers, newsreaders, and radio all make appearances).

We are chucked around, following performers who are charming and companiable at one moment, feckless and conniving the next. Costumes are cut to the period—but look again, they are steam punks, bike couriers, her wig is a mop. The make-up is wonky vaudevillian. Props are jute cloth and cardboard, but in close-up each is cleverly engineered. This creative double-dealing (or, in Brechtian lingo, Verfremdung, “making strange”1) is most pronounced in Fleischhacker, played at sections by Louis Goodwin, Conrad Williamson, and—most devilishly—Seth Kruger, the wheat trader who reassures investors while throwing the market. Fleischhacker(s), their accomplices, reporters, and victims, thrash around surrounded by Brecht’s sources, which are pinned to the walls: postcards, a diagram of the Chicago Pit (the trading floor), a JD Rockefeller cut-out, and translated passages from his works.

Phoebe von Held, the exhibition’s curator (with Tom Kuhn, Alex Sainsbury and Iliane Thiemann) and performances director, has described Fleischhacker as “the nucleus of this exhibition.”2 Breadshop seems to be its corollary. Here, a baker’s assistant and her children are evicted following the 1929 Crash. Efé Agwele plays widow Mrs Queck, lamenting her fate as others from “the depths” exploit her in chorus. We’re in the building’s old servants’ quarters, in the shadows of a city ravaged by neoliberalism, at the centre of a world still cleaved apart by empire. A window is open to it, via which the actors romp in and out. Passers-by stop and stare. This is Brecht’s distancing effect, allowing life to infuse work that remains porous, noisy, and tart.

Stripped of the performance, the exhibition still presents a worthwhile post-mortem on the place of fragments in Brecht’s creative life. But together, they are electric. Brecht recognised his fragments’ worth, guarding his papers carefully, even if the ideas within them were sprawling and many works were left unfinished. He even left notes for his obituary: “Write that I was awkward, and that I intended to remain awkward after my death. Even then there are still certain possibilities.”3 Such possibilities are elegantly marshaled by von Held et al. In an age of unregulated and unrelenting disinformation, the enterprise is both impactful and timely. Brecht’s message survives: don’t be sedated. REVOLT!

See Isabel Jacob’s recent E-Flux Notes piece on this approach.

Phoebe von Held, “Fragments and Images,” in brecht: fragments (London: Raven Row, 2024), 15.

Iliane Thiemann, “Fragments by the Metre: A Fragmentary Stroll Through the Bertolt Brecht Archive,” trans. Kathrin Luddecke in brecht: fragments (London: Raven Row, 2024), 34. Originally published in Neue Zeit (Berlin, 19 August 1956), Karl Kleinschmidt, “Wir sind der Mensch von Sezuan. Bert Brecht – Erinnerung und Vermächtnis.”