The deep boom of a subwoofer meets you on the stairs to the small gallery. Inside, a two-channel video projected across opposite walls shows barren landscapes with figures moving through them, close-ups of plants and foliage, and more besides, the imagery by turns sped up, slowed down, color-adjusted, and layered. One half is framed to the dimensions of the space; the second is projected at an angle, so the pictures invade the ceiling and floor. It is a hypnotic, unnerving assemblage.

On the gallery floor, between the two projections of Until we became fire and fire us (2023–ongoing), stand metal barricades, like sections of a security border, on which printed frames from the film are attached. Above, sheer fabric banners hang, printed from further images culled from the video. To one side, copies of a newspaper—the New York War Crimes, mimicking the design of the New York Times—are piled up on a pair of bricks and available for the visitor to take away. It tells a century-old story of Palestinian struggle and Israeli aggression through a succession of commissioned texts.

The materiality of all this stuff is in stark contrast to the subject of the thirty-two-minute, mixed-media work that lends this exhibition its title: the brutal erasure of the village of Tantura, a Palestinian fishing village, by Israeli forces during the Nakba, in 1948. As many as 200 of the village’s residents are believed to have been massacred; those who survived were expelled from the settlement.1 Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme’s work traces the total dematerialization of a community, its presence left only to memory, and reveals a landscape burned to the ground, cacti sprouting where once people lived. “The land will testify,” read the fragmentary text that subtitles the film, in purple English and Arabic text. “Where there is violence there is always a trace. An echo buried.” The video pans to the beach and car park where the village once lay. The aerial footage appears in negative, like an x-ray of a modern settlement beneath which trauma lies.

How to make and show art about Palestine now? How to make work that cuts through the culture industry’s intricate entanglement with outside interests and prejudices? It is unlikely this work would be shown in, say, Germany at this particular moment (though it’s worth noting that the first iteration of the work was co-commissioned by and previously installed at the Sharjah Biennial, and later at the private Fondazione In Between Art Film in Venice). Here, however, in a private patron’s space in a country traditionally sympathetic to the Palestinian cause, the themes of genocide and blood-soaked landscapes resonate with Brazil’s own ongoing erasure of indigenous lands. Abbas and Abou-Rahme have eschewed hectoring declarations (the newspaper is the only potential misstep in this regard) in favor of a sophisticated, formally nuanced work of art.

Your eyes are constantly drawn to the subtitles. As a result, the imagery—projected onto opposite walls, each showing footage inset and layered over each other—washes over you. At times barely conscious of what specific images depict, your attention is held by the English and Arabic words as you constantly turn your head to catch the screens at opposite ends of the space (additional Portuguese might have been helpful for local audiences). It is a formal metaphor, perhaps, for the bewilderment of today’s war. The violence of 1948 is unrelenting, and the blizzard of information and livestreamed horror have done little to stop it. Show and distract: this is the constant state of our new media age.

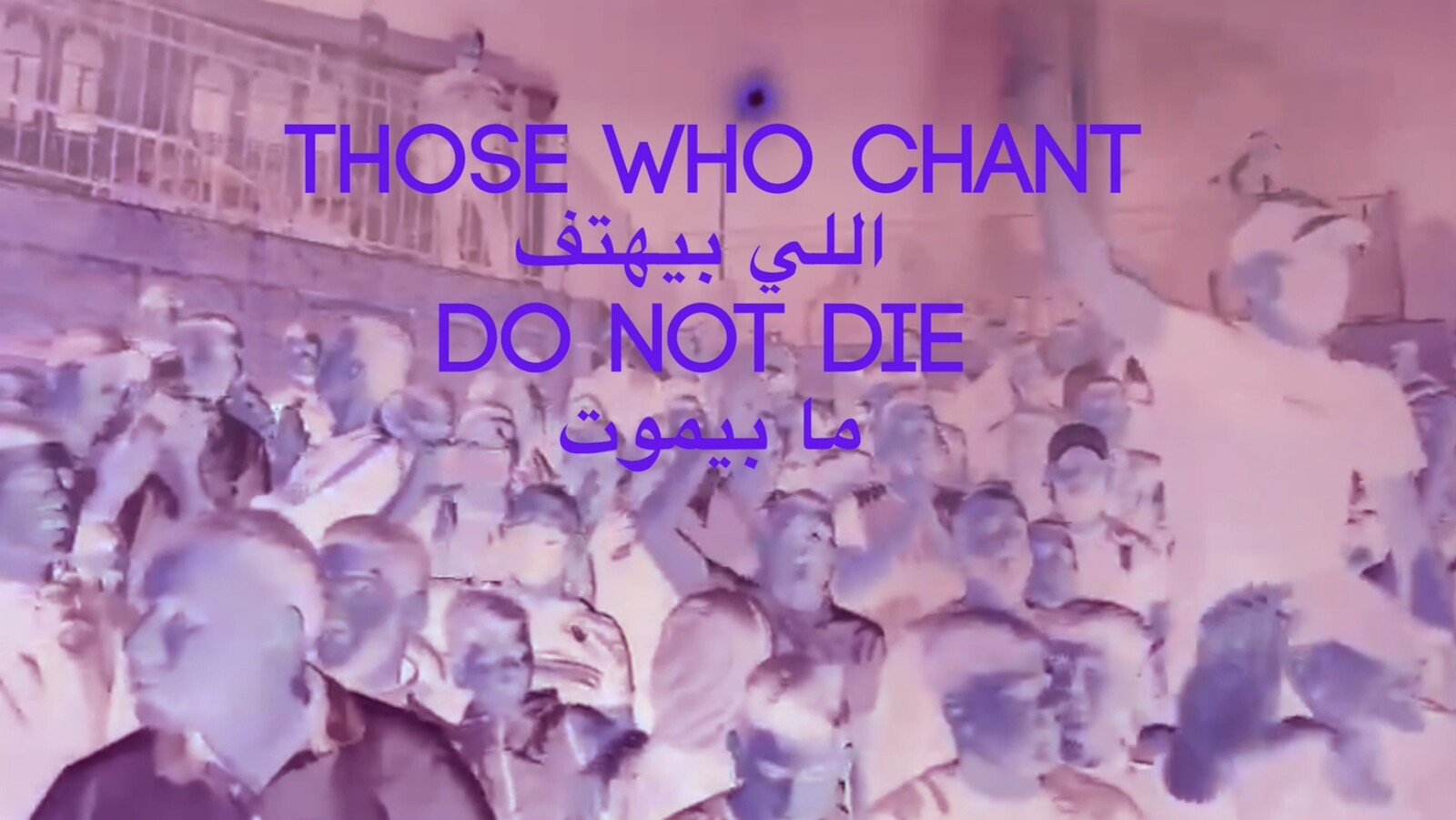

A third of the way in, the tempo of the video changes. Drumming starts reflecting the Arabic dancing we see on screen, a thrusting beat that ramps up the sonic quality as the images become more frantic—joyful, angry, but above all determined. “The fire / raged and raged / until we became fire,” reads the text. A couple dances, then a crowd. The lives of those killed at Tantura memorialized in music, but their suffering has not gone away. A man appears muttering incantations while pacing across a sandy wasteland: a fugitive, the subtitles suggest, who has been “dragged from prison to prison,” who can’t walk the streets of Jerusalem in case he is asked for his ID. In the closing frames, this lone figure is replaced by a crowd. The subtitle reads: “those who chant do not die.”

After exiting the gallery and leaving behind this exhausting, brilliant work, it is this noise that stays with you. Abbas and Abou-Rahme are master soundtrackers. The video’s seven-channel audio mixes field recordings, live-recorded music and singing, and dubbed music with a drone that permeates the film and fills the small gallery to a suffocating degree, putting you on edge and getting into your bones. As a journalist, I’ve interviewed people who have lived through conflicts in other parts of the world, and they always speak of being constantly alert to sound, like dogs at night. Sound is always the first indication of danger, an aural violence that is ever-present, potential even in silence. While those in power remain indifferent to images of Palestinian suffering, Abbas and Abou-Rahme’s work suggests that violence, no matter how deeply buried, will continue to echo across the land.

Bethan McKernan, “UK study of 1948 Israeli massacre of Palestinian village reveals mass grave sites,” the Guardian (May 25, 2023): https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/may/25/study-1948-israeli-massacre-tantura-palestinian-village-mass-graves-car-park.