Glenn Ligon’s takeover of the Fitzwilliam Museum is so “all over the place” that I had to come back for a second visit to see things I’d missed the first time around. It is relevant to his nuanced but pervasive intervention that the museum was founded in 1816 when Viscount Richard Fitzwilliam left his collection of art and cultural artifacts to the University of Cambridge with a bequest to construct a museum of art and antiquities. This leaves it with twinned affiliation: both to an esteemed educational institution and to a landowner whose fortune derived in part—as recent research by the museum has unearthed—from his grandfather’s investment in the transatlantic slave trade.

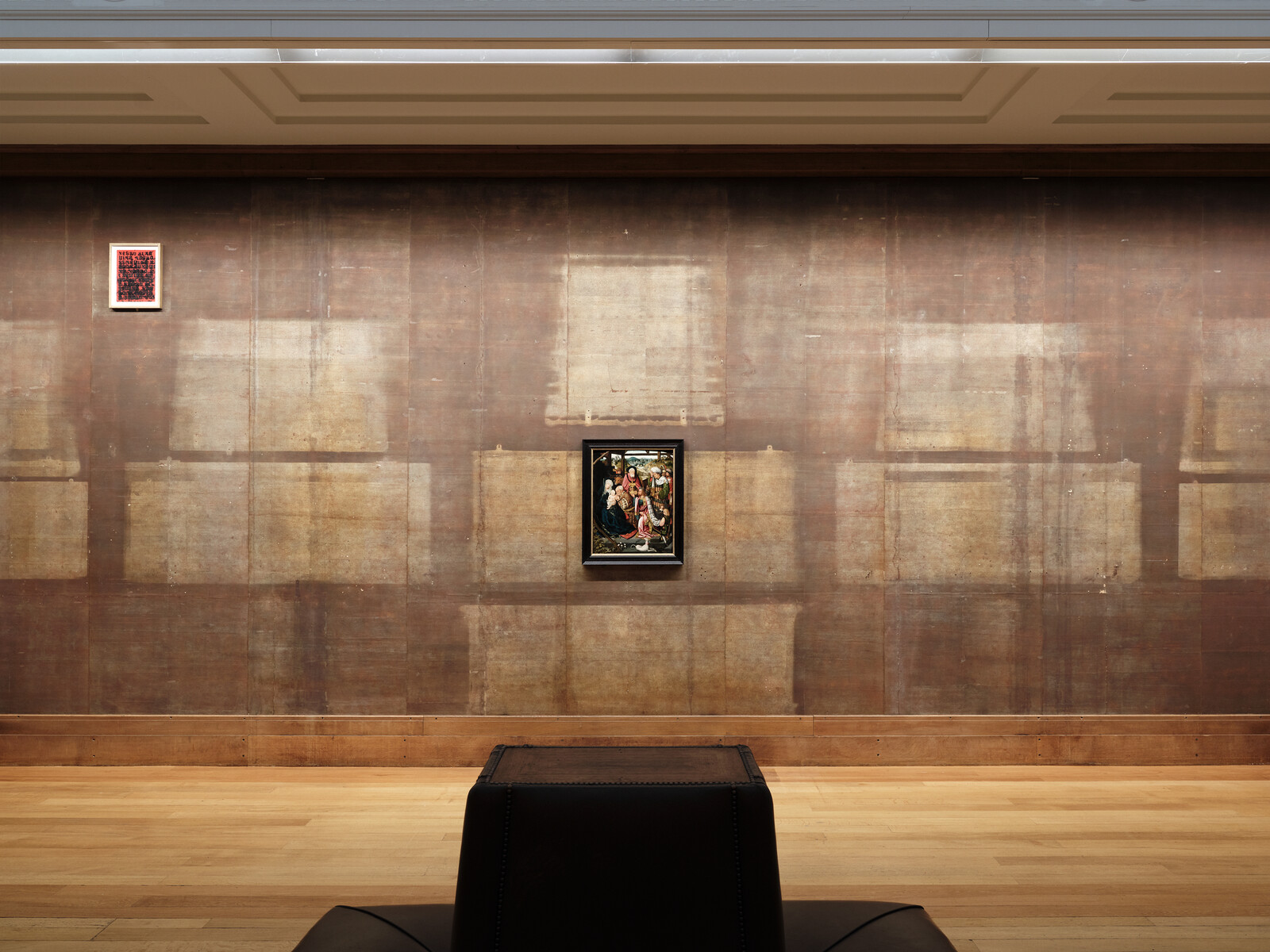

Ligon’s multimedia work often interrogates race, even if it cannot be reduced to that subject, and his subtle interventions into the museum’s collection are consistent with his multilayered practice. On the ground floor, Ligon has selected objects from the museum’s collection of porcelain from Europe and Japan, showing them alongside his take on Korean Moon jars, painted a blackish hue instead of the traditional white. On the floor above, Ligon has rehung flower paintings from the collection of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Dutch still lifes, rearranging them to form new connections. Written on red cards instead of the standard white, Ligon’s annotative texts are casual in tone, feeling as personal as diary entries.

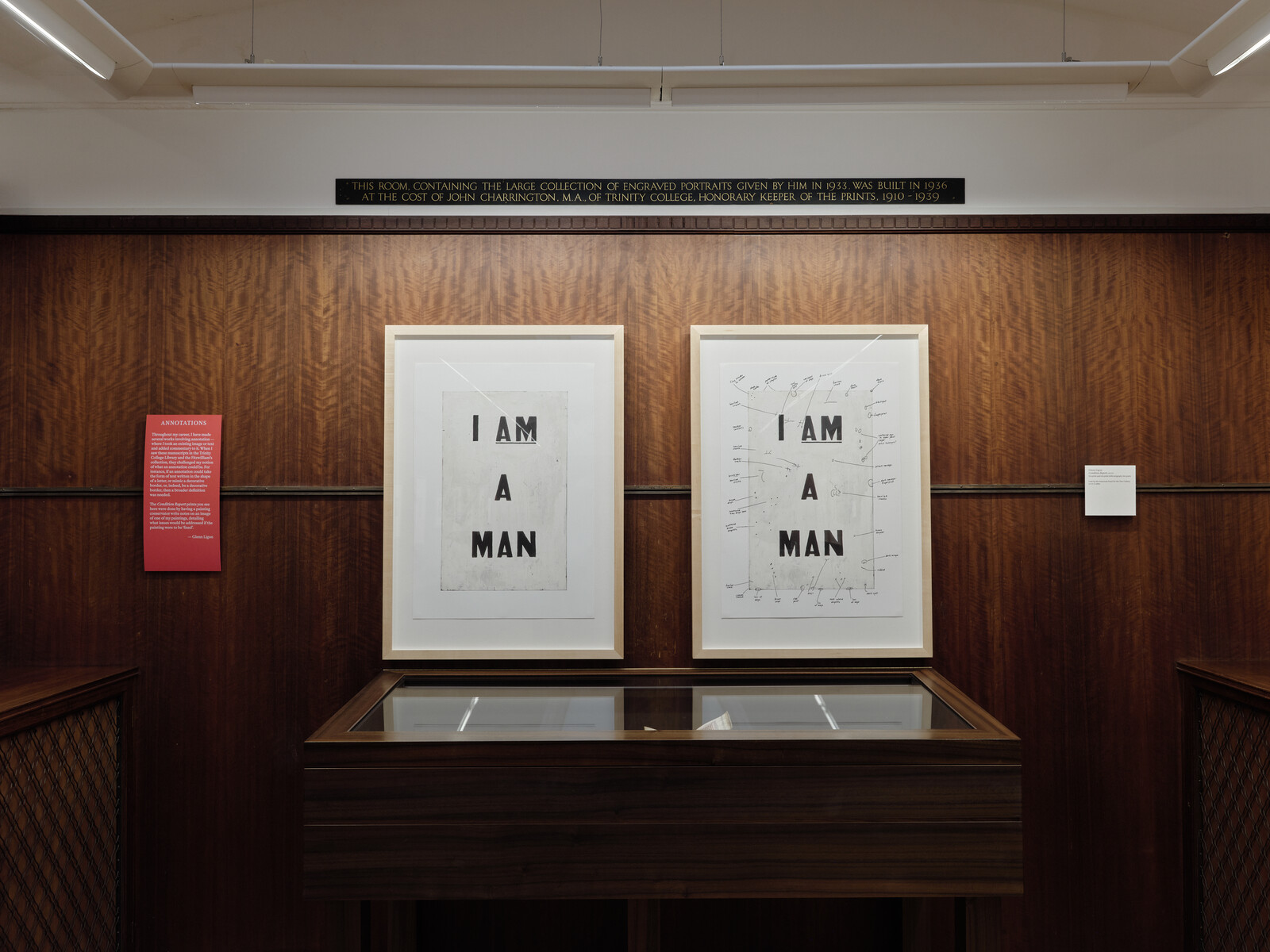

In a darkened room, Ligon has pulled works from the museum’s collections of prints, the most notable by Edgar Degas and the recently deceased Frank Auerbach, with his own works shown side-by-side. Among these is Condition Report (2000) made up of two print reproductions—one annotated, one bare—of Ligon’s 1988 painting Untitled (I Am a Man), taking a slogan made famous by sanitation workers from the Memphis Department of Public Works striking to demand safer working conditions in 1968, and transforming it into an art object. The print on the right-hand side of this diptych is annotated with conservator Michael Duffy’s notes on the painting’s condition, giving us a glimpse into the ways objects of protest become artifacts and are accessioned and preserved in the official repositories of culture and history. The dehumanization of Black people in the fight for civil rights is here brought into a museum founded, at least in part, on their ancestors’ exploitation and forced displacement.

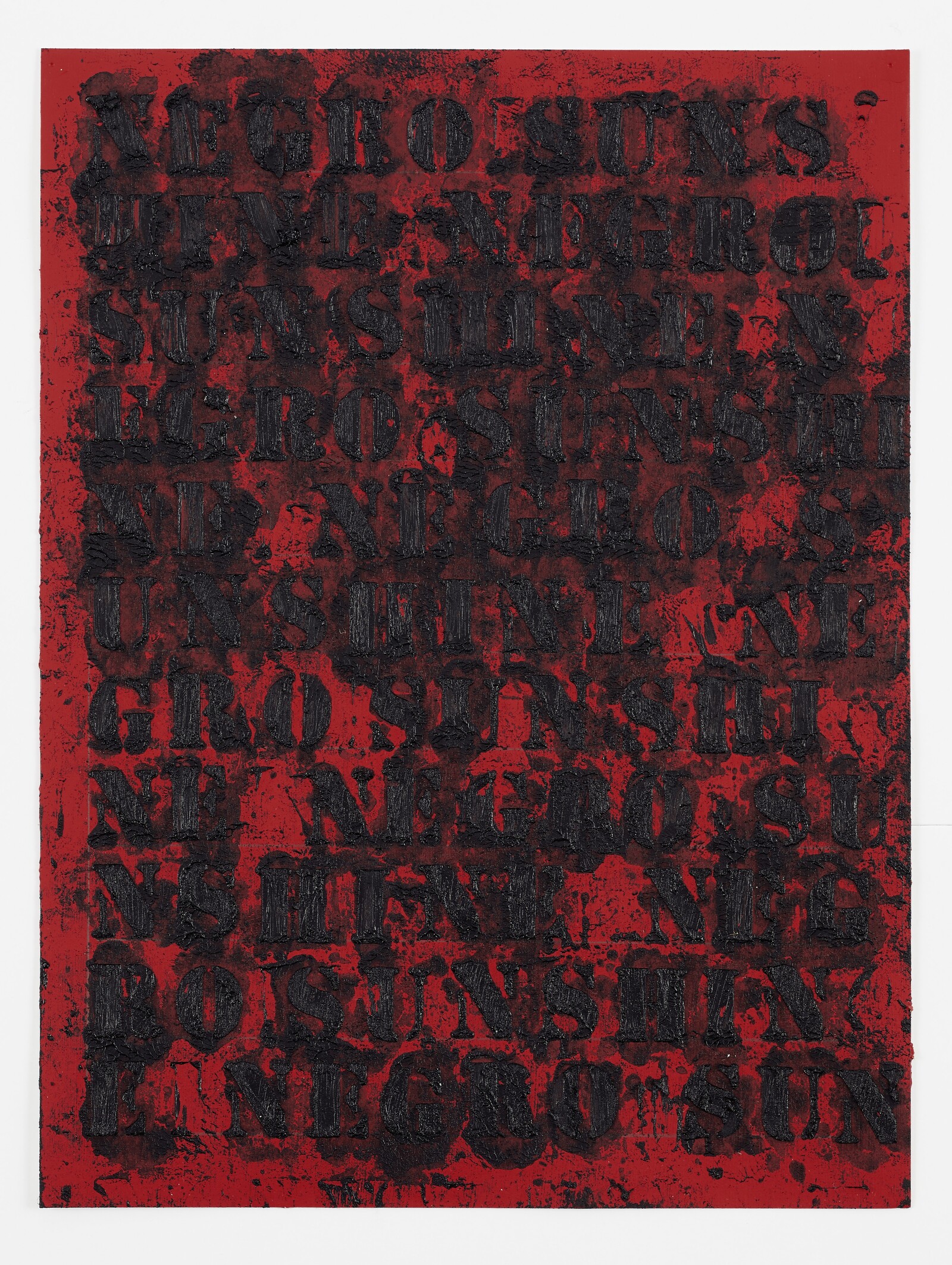

The series of works on paper titled “Study for Negro Sunshine (Red)” (2018–ongoing) punctuates the mostly representational paintings from the museum’s permanent collection in three galleries on the top floor. Ligon has been working with this phrase “negro sunshine” for over two decades, having first come upon it in Gertrude Stein’s story “Melanctha,” part of Three Lives (1909). The phrase is used in a description of a Black female character, Rose Johnson, who, like many of Stein’s Black characters in the novella, is flattened by the tendency to “trade in racial stereotypes.”1 Returning to this phrase over and over again through the years, writing it in stenciled black letters overlaid by black oil stick, Ligon renders it almost illegible, as though to strip it of its potency through repetition: a muted homage to Stein’s radical style, embedded in critique.

James Baldwin‘s essay “Stranger in the Village” (1953) serves as a reference for an eponymous series of works in a polygonal room near the end of the exhibition. Again, Ligon has considered this essay for decades, his relationship to it shifting over time, and again he uses obscuring gestures. On this occasion the near-illegibility of the black lines mirrors the way Baldwin left out details in his recollection of his time in Switzerland, such as his stay at the chalet of his lover’s family. Was this because he wanted to preserve the privacy of his married lover? He may have felt that this might imply some privilege on his part, or perhaps he was reluctant to share all his experiences as a queer Black man in the late 1940s–50s. The answer remains unclear—just as Ligon plays with what we can see of his literary references. “Part of my painting,” Ligon says when reflecting on these omissions, “was to think about that opacity, the things that language cannot do.” 2

Following recent tendencies in museum studies, the Fitzwilliam is working to address its history. Putting on exhibitions such as “Black Atlantic: Power, People, Resistance” and the forthcoming “Rise Up: Resistance, Revolution, Abolition” is a part of this. Ligon’s intervention into the collection might be understood as consistent with this work but his multi-pronged approach—not only exhibiting his own work but interpolating it into the permanent collection, which in the same process he reconfigures and reinterprets—also raises questions about predominant methods of collection and display. By eschewing traditional ways to tread his own desire paths, he institutes and encourages interesting, fresh ways into museum collections. This exhibition is raised above academic curatorial exercise by Ligon’s own compelling work as an artist. By giving Ligon license to pull from the collection and place his work among it, curator Habda Rashid has put together a show that locates the artist’s practice at the nexus of homage and critique, expanding that ambiguous space where there is endless potential for creating new meanings and associations from the source material.

Glenn Ligon’s text on wall label.

Glenn Ligon and David Dibosa, “In Conversation,” in Glenn Ligon: All Over the Place, eds. Glenn Ligon and Habda Rashid (London: Paul Hoberton Publishing, 2024), 40.