If your first associations with Colombia are cocaine, paramilitary violence, and the rapacious plunder of natural resources by neo-colonialist corporations, then you are only half right, according to this spirited, unkempt, and organizationally flawed exhibition of Colombian artists at The Box, Los Angeles. Along with all these clichés (eagerly resold to Western audiences through film and television), Colombia is a society of familial warmth and communal resilience, a place where humor, love, and magic play important roles in the survival of its people.

Curators Víctor Albarracín Llanos (who is Colombian) and Corazón Del Sol (who grew up there) allow all of these narrative threads to entwine through the work of 32 artists, most of whom live in Colombia but some of whom now reside elsewhere. One is Los Angeles-based Gala Porras-Kim, who fled Colombia when she was a child, packing hastily in the middle of the night after her family was threatened. The small trove of items she brought with her is arranged on a low table as an untitled and undated installation: comics, letters, some dried leaves, and a cheat sheet for Mortal Kombat 3 (1995). Collectively, the objects reaffirm a tired narrative of dysfunctional Colombian life, but individually they are testament to its inverse—Porras-Kim’s apparently happy and normal childhood.

Across a doorway in the gallery hangs a bead curtain (Fiebre Super Nórdica, 2016) by Nicolás Vizcaíno Sánchez, its blue, green, orange, and red pattern recalling an infrared digital display. The design is a reference to the POV of the alien in the first Predator film (1987), whose face appears also in the beadwork on a traditional Emberá necklace, hanging beside the curtain. Sánchez’s slightly convoluted conceit is that since, in the movie, the terrifying Predator intimidated Americans from entering the jungle, by resurrecting the monster he might protect the Emberá Katío people, who have been displaced from their lands in Chocó by paramilitary activity connected to internationally funded resource extraction. (Before the 2016 ceasefire, the curators told me, the drug cartels performed a similar deterrent function.)

An impressive ink on paper drawing by Carolina Caycedo, Genealogy of Struggle / Genealogía de la Resistencia (2017), shows a broad tree inscribed with the names of environmentalists around the world who were murdered in the past year. Shockingly, these are too numerous to count, and many of them (though by no means all) are Colombian. However, the drawing’s placement, sidelined in a cinder block-walled corridor, seems almost disrespectful. Which brings us to the main weakness of the show: the curation feels as if it is driven by the eternal dilemma of art school degree shows—how to fit too much into too little space—rather than by the opportunity to enhance meaning through judicious placement of works.

Llanos and Del Sol may not wholly disagree, their approach seemingly governed by the belief that more is more, and that unforeseen cross-pollination and discourse amongst artworks is not just to be welcomed, but actively engineered through the convivial intermingling of works and a light curatorial touch. This dynamic is compounded by another factor in the organization of the show: since many artists are unable to travel for the exhibition, each has been paired with a Los Angeles-based emissary, who is also encouraged to contribute their own response to the work by their counterpart. Responses are being added during the course of the show, although some local emissaries were present from the beginning and activated works on their partners’ behalf. At the show’s opening, L.A.-based Elyse Poppers (best known as Paul McCarthy’s muse) could be seen pressing her face to a three-inch hole bored through the gallery’s exterior wall and hissing at men who walked by on the street. The performance, a work by Colombian Liliana Vélez, is titled -pss-pss- (2012/17).

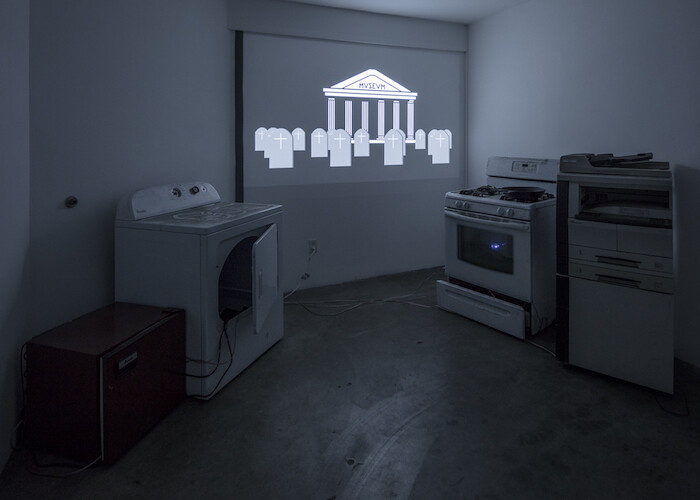

The best works in the exhibition lean only lightly, or not at all, on the potentially all-consuming tropes of contemporary Colombian struggle. In one corner of the main space Te Amo (2017) by Henry Palacio, a huge sagging phallus made from black trash bags inflated by a fan, bears the eponymous message, crudely applied in white tape. The celebrated Colombian painter Wilson Diaz is represented by two oil on unstretched linen paintings, one double-sided and free-hanging. Palmera (2017) welcomes visitors to the gallery with a picture of palm trees that is, in Wilson’s rendering, just a poster on a bare brick wall with a table fan and a curtain placed in front. As with many other works in “Dysfunctional Formulas of Love,” the painting is as much a conjuration of a fantasy (though whose fantasy is unclear) as it is a document of present conditions. It is simultaneously realist and romantic. A statement of love is a declaration of faith in what might be, as well as what is.