Long ago, before the euro and the internet, I was a young backpacker on my first trip to Greece. Beaches were broad and unpeopled. I traveled on boats to islands large and small, always noticing the tiniest ones jutting from the Aegean like beacons or sculptures. In the midst of youthful island-hopping, the romance of the Aegean and the Mediterranean—their mythologies and histories—caught me.

German-Greek artist Christina Dimitriadis—whom I met years later and whose art and life has taught me much about what one could call the contemporary Greek condition—takes the act of moving between isles as the most direct point of departure for her photography exhibition “Island Hoping,” curated by art historian Denys Zacharopoulos. The notion is embedded in the punny title (I’ll get to the “hoping” part in a moment). But like any of Greece’s 6,000-odd islands, this show possesses multiple layers and approaches.

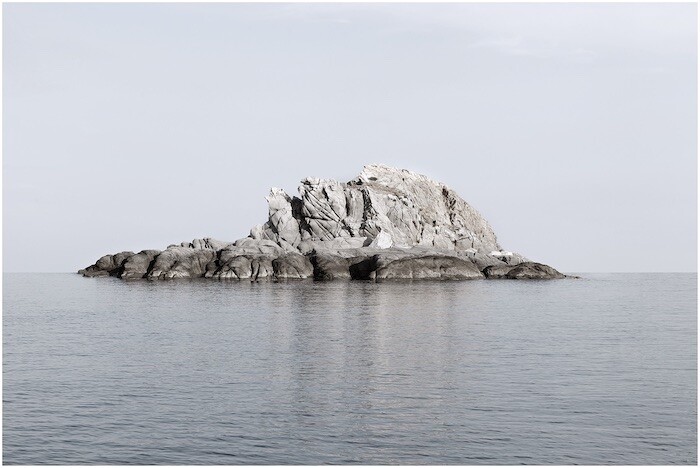

Along the far wall of the white, windowless exhibition space are 30 photographs (all 60 by 90 centimeters and collectively titled “Island Hoping”). Each depicts an island or group of islands too small for human habitation rising from the sea, centered in the frame. The images share a horizon line where water meets sky, just below the central axis. Hung at eye level at points around the room are three more groups of photographs: the space is so long that viewers must move as if forced to navigate the rocks, reading them either as geographical documentation or as a metaphorical poem in several parts.

Hues are muted; the skies appear in a narrow range of the palest blue, their wispy clouds like brushstrokes. The sea, also captured in a painterly way, is at times calm, at times darker and dynamic. The skerries—as such small, uninhabited islands are known—are like stone sculptures, some jagged and nearly white, others rounded and dark. There are stripes, crevasses, sharp surfaces, smooth mounds. Look again and a few skerries begin to resemble figures: Island Hoping 6 could be a reclining man, 15 a pyramid, 29 a lion with its paws outstretched. Some cast dramatic shadows in the water, others barely reflect.

Much of Dimitriadis’s previous work has explored the dialectic between private and public with ethereal self-portraiture (often with family and friends) shot in intimate domestic interiors; what the ancient Greeks called the oikos, a word incorporating the family as a social unit, its people, and the structure(s) it lives in. Here she confronts this tension again, this time looking toward the ultimate exterior—nature, unpeopled and untamable. Although the works’ serial format hearkens to the industrial series of Bernd and Hilla Becher, she does not attempt to classify, nor is this a take on the art-historical seascape.

“Island Hoping” is more intimate and much broader-reaching. Knowing Dimitriadis and what moves her practice, the show is her most ambitious comment on both personal identity—it was in part inspired by a photograph of her German mother’s home on the Heligoland archipelago in the North Sea—and contemporary politics.1 Although Dimitriadis was raised in Greece, her binationality has remained a source of reflection, especially in the past decade, as economic conflicts between Germany and Greece have interlocked the countries in a kind of stalemate. As the artist has said of her Southern side, “Every Greek had to separate from part of his/her own history and create a new identity.”2

“Island Hoping” represents this separation and the search it has launched, an outward remapping and an inward reorientation amidst today’s geopolitical storms. Dimitriadis began photographing the first skerries in October 2015. Over the same period, thousands of asylum-seekers were crossing the Mediterranean. Dimitriadis’s photographs do not aestheticize misery but rather question whether these skerries represent destinations or dangerous obstacles, if they signify dreams or nightmares. Many are located near Ikaria, an island famous for its people’s longevity. But Dimitriadis also discovered that the area is thick with historical shipwrecks and that these skerries were known as Anthropofagos, “people eaters.”

What to make of the optimism alluded to in the exhibition title? What hope is there when multitudes of families like Dimitriadis’s have been affected by Greece’s ongoing crisis and refugees continue to drown in these waters? In these images, the application of a meditative visual language to contrastingly solid and mutable elements suggests that new mythologies can emerge from the unpredictability and ephemerality of the sea, of history, of life, as they have here for millennia.

Heligoland is also a tourist destination for northern Europeans, and like some Greek islands a historically strategic location in geopolitical conflicts.

Barbara Piwowarska, ”Christina Dimitriadis. Technologies of the Self,” see: https://wsimag.com/art/14553-christina-dimitriadis-technologies-of-the-self.