May 13–November 26, 2017

The reign of Stella Kesaeva and the Stella Art Foundation over the Russian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale ended in 2015. Over the course of three biennales, they showed western audiences works by the artists who secured Moscow conceptualism’s place in art history, and transformed it into an export commodity (in the good sense of the word). Moscow conceptualism is not, of course, the equal of Russia’s historical avant-garde, but it can claim second place in the canon. The 2015 Venice Biennale also marked the end of the era of grand narratives in Russian art.

The final exhibition with Kesaeva as commissioner proved that exporting conceptualism had been exhausted. It was clear the Russian Pavilion needed to look for a different way of doing things, to get away from the conservative, spotless presentation of heavyweight canonical art that everyone adores. Ilya Kabakov, after all, was shown in the Russian Pavilion way back in 1993. His friends Andrei Monastyrsky (2011), Vadim Zakharov (2013), and Irina Nakhova (2015) represented Russia at the biennale two decades later. Expectations for the 2017 pavilion were thus considerable. Organizers were faced with the sticky problem of devising a means of representing Russian art that syncs with the international art context. To a certain degree, this implied outlining (or, at least, sketching) the history of contemporary art.

Semyon Mikhailovsky was appointed commissioner of the Russian Pavilion in 2016. At the time, he was also commissioner of the Russian Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale, an appointment which had been tainted by controversy. Mikhailovsky had assumed the job after the previous commissioner, architecture critic and journalist Grigory Revzin, was abruptly dismissed a few months before the exhibition’s opening.1 Revzin commented laconically on the situation: “One should not write about Crimea.” No one has problems understanding the Russian Culture Ministry’s message. Mikhailovsky became in many ways a more amenable figure, whose statements would not cause concern.

Seemingly responsible for contemporary art production per se, the Venice Art Biennale is more influential and unorthodox than the architecture shows, at which presentations are formalized and filtered by professional organizations. However Mikhailovsky’s appointment to commission the Russian Pavilion surprised many, though it might have been expected in light of Russia’s current cultural policy. The desire to kill two birds with one stone—what you might call “skimping on names”—has become a telltale characteristic of governance in Russia during Putin’s third term. It is no secret to anyone that the rotation of personnel in politics has been reduced to a minimum. When such rotation does exist, it often follows the feudal model of posts handed down from fathers to sons. In general, managing such complicated systems as Russia executively means minimizing the number of mediating links between powers. What has happened to Russian contemporary art is no exception. True, there are certain provisos: power can be handed from mother to daughter, which provokes less criticism from the liberal sections of Russia’s patriarchal society than its transferal from father to son, but the rationale is the same. In this sense, the circumstances surrounding the pavilions in Venice jibe perfectly with the current national trends. If repairing a village road, subsidizing regional sports clubs, and drawing up the repertoire at a Moscow theater are impossible without writing a letter to the country’s president, why search for other explanations when it comes to contemporary art?

Mikhailovsky’s primary claim to fame is as rector of the Repin St. Petersburg Institute of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture. In other words, he is as remote from contemporary art as seems possible. Russian Culture Minister Vladimir Medinsky has stated, however, that “contemporary art is everything done today,” so there are no formal contradictions. In an interview published last year, Mikhailovsky shared his opinions about the future exhibition in Venice. “There is this young guy who is talented and gifted. He does beautiful analytical drawings we would like to show in the pavilion. Other students will go with him.”2 It was not clear who Mikhailovsky meant by “we.” It is obvious that taking students from his institute to show their works at the Russian Pavilion and, thus, one of the principal biennials of contemporary art in the world could only have been Mikhailovsky’s personal wish. People with a stake in the matter waited for a long time for explanations regarding this abstract “we.” The biennale was approaching, but Mikhailovsky had not yet named a curator. The news came only a couple of months before the opening. Mikhailovsky would serve not only as commissioner but also as curator, and he would exhibit Grisha Bruskin, Sasha Pirogova, and the Recycle Group in the pavilion.

The answer to the question of why the idea to exhibit students from the Repin Institute was ultimately dropped can be found in the catalogue’s introductory essay. Mikhailovsky “devoted some time to finding talented young men and women,” but was subsequently “wowed” by Bruskin’s installation. The essay is an amazing thing generally. It is a kind of manifesto on the work of the new commissioner-cum-curator. The only thing lacking is that he failed to satisfy the desire of many people for an explanation of why he took on both jobs. But this has become almost customary in modern Russian society. The authorities do not consider it necessary to explain anything to rank-and-file Russians. This applies to the political authorities, the financial authorities (the oligarchs)—and to the art authorities.

On the other hand, Mikhailovsky’s essay reveals his attitude to conceptualism. He makes ironic comments about Kabakov and summarizes the oeuvre of the conceptualists, who nevertheless “earned the right to be exhibited.” So the Russian 2000s and 2010s also ended in Venice. Gone are the conceptualists once fashionable in the west. Henceforth, things are going to be about the “fresh-faced youth,” although these artists were ultimately passed over for this year’s pavilion in favor of an artist who grew up in the Soviet Union and was a product of the Soviet underground art world. Grisha Bruskin’s towering achievement as an artist, if we trust the brief biography supplied in Venice, was the sale of one of his works for £220,000 (more than Kabakov!) at Sotheby’s landmark Moscow sale in 1988. This detail should give us to understand that Bruskin, although not a direct adherent of the Moscow conceptualists, at the very least insists on being regarded as occupying the same terrain. Mikhailovsky’s own attitude to the conceptualists is even more confusing, and his desire to break with the practices of his predecessor has obviously not taken him very far afield.

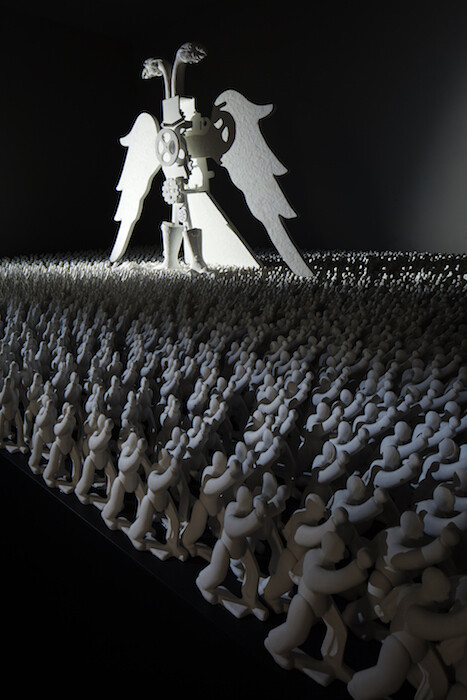

Bruskin is yet another compromise of 2017. The commissioner-cum-curator explains his presence in the pavilion in terms of the effect of what he saw in the artist’s studio on him. This is an important detail, emphasizing the “manual control” of art, coupled with the incorruptibility of the artist’s will. The concept of the pavilion was derived from Bruskin’s works. Theatrum Orbis Terrarum is the title of a sixteenth-century atlas, the first modern geographic atlas in history. It was translated into Russian as, literally, “Spectacle of the Terrestrial Circle.” According to Bruskin’s own testimony and that of Italian art historians, as compiled in the catalogue, the artist has for some time been occupied by the topic of the spectacle and the concept of the theater of memory. His installation deals with “changes of scenery.” Three rooms are chockablock with sculptures, reminiscent of the quasi-Surrealism produced by the so-called left (liberal) wing of the Moscow Union of Artists in the late Soviet period. A gigantic two-headed eagle hovers over a mob of soldiers under arms. The monstrous inhabitants of the second room stand as if preparing to go on stage, although there is no stage. Life is a theater, a spectacle with no end that has congealed during a change of scenery; people are both the actors and the only spectators. These are baroque commonplaces.

The exhibition does have a political aspect as well, which Bruskin himself has served up as a classic post-dissident truth about the machine of the totalitarian state and its cog-like citizens, although the two-headed eagle unambiguously refers to the present, while the soldiers can be recognized as the riot cops sent into Moscow during public holidays. It is impossible to find any better-defined message, but even this unfocused view of politics leads to curiosities. Thus, in his commentary, the curator unexpectedly identifies the characters—Bruskin’s soldiers or toy soldiers, probably—as “protesters.” If we extrapolate Mikhailovsky’s rationale, we can assume the eagle functions, as it were, as the guardian of the Motherland’s cultural values from collapse and degradation.

In his response to the biennale, Radio Svoboda journalist and independent publisher Dmitry Volchek wrote he had vowed not to criticize the Russian Pavilion, knowing the conditions under which it was produced. I would be ready to embrace Volchek’s position if the entire pavilion had been given over to Bruskin, with his vague (or, if you will, spiritual) hints and endearingly obsolete arguments with the commissioner. However, the maxim that “contemporary art is everything done today” (and, apparently, everything done by the young and contemporary) added several new layers of meaning to this already pompous dinner party chitchat that, finally, caused me to lose the thread of the conversation.

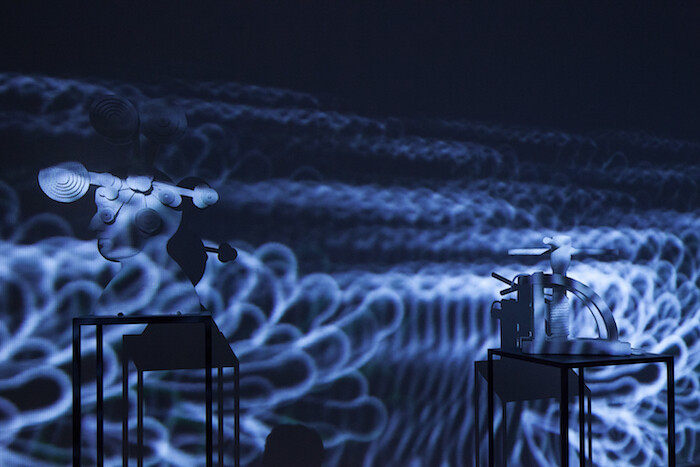

The pavilion’s lower level has been given over to Recycle Group, two artists from Krasnodar (Andrey Blokhin and Georgy Kuznetsov) whose work explores the anti-utopia of modern technology, and Sasha Pirogova, a video artist who researches the dynamics of the human body in space (tellingly, she was educated as a physicist). Recycle Group, whom it would be hard to accuse of lacking honesty and diligence, present viewers with a white space. It is populated (as in Bruskin’s installation) with white sculptures which are, however, hidden, embedded in the walls and only visible via digital interfaces. The metaphor and subject are borrowed from Dante: sinners frozen in blocks of ice. It is the show’s key image, repeated in all commentaries on the exhibition. The curator’s desire to deal with a lofty style and enduring subject matter is easily divined here. Recycle Group’s sinners are sinners in virtual space, sinners banned by various internet monitoring systems (i.e., switched off from their virtual immortality, meaning they have been killed.) Viewers can see the installation only by downloading an app and pointing their smartphones at the white blocks, on which a completed image fills the screen. Unfortunately, the internet works only intermittently. As is usually the case, the Russian Pavilion has been busy, and so it is not always possible to download the app. It is an ironic complement to Recycle Group’s piece, which refers to the rhetoric of Russian MPs who have been criticizing the internet and the dangers it allegedly conceals. This is the anti-utopian nature of the virtual world, the freedom and immortality it once promised now turned into an ice cave of sorts, from which you cannot escape until someone frees you via a smartphone screen.

Amazing visitors with “new technologies” and “new media” has become a familiar tactic of the Russian Pavilion (there were many such tricks during Olga Sviblova’s tenure as curator in 2007 and 2009) and many petro-states. But the post-internet has reigned supreme for the past five years or so; in other words, art that brings us back from virtual blocks of ice to reality, showing us the world has changed beyond recognition while we were wasting our time chasing unrealistic dreams. You can relate to post-internet art however you like, but you can set your watch by it. So while WiFi and apps for virtual sculptures are being handed out for free in the Russian Pavilion, over in Estonia’s3 you will find the leader of the new post-digital generation, Katja Novitskova, using her now-canonical trompe l’oeil cardboard sculptures to tell viewers about life in the desert of the real. This comparison gives you an idea of Russian art’s place in the world.

It is curious that an interest in the eternal subjects supplied by literary classics is not only present in the Russian Pavilion. Given the supremely boring, disastrous International Pavilion, the Biennale’s big hit has been Faust (2017) by German artist Anne Imhof. Here too, the combination of hi-tech with the bathos of universal themes have played a dirty trick on Russian art. Compared with Imhof’s ascetic, impeccably stylish living sculptures, the Russian Pavilion’s frozen freedom fighters appear, despite their youth, hopelessly outdated.

The Russian Pavilion is rounded out by Sasha Pirogova’s video work Garden (2017), which is afforded the least space and attention in Mikhailovsky’s theater. The ten-minute video has been shot and edited in such a way that it is impossible to shake the feeling you are looking at an unfinished sketch by Victor Alimpiev or an early piece by Polina Kanis. A mystical dance unfolds onscreen: a circular procession by tree-people growing out of pebbles, the same pebbles that crunch underfoot when you visit the Giardini. In an airless space, seemingly filled only with lights, the fluent movements of the dancers are meant to put viewers in a bright and “positive” mood. If we invoke the obvious comparison, as obvious as all the metaphors in the show, we find ourselves in a kind of paradise after the phantasmagorical sufferings of the present day, after we have suffered protesters and the internet. An extremely abstract explanation hangs at the entrance to Pirogova’s room: it tells us that the eternal struggle between light and darkness is only an appearance. There is a grain of theoretical substance to this. But we are simply late with the diagnosis once again, albeit not so late as to amaze viewers. Russian traditionalism and “eternity” do not quite make the grade when it comes to a radically Other archaic fossil set against the present. As it is, the modern world of hypernormalization and hybrid wars lost any clear gradations between light and darkness way back during the Society of the Spectacle. The fog of “Theatrum Orbis” adds little if any significance to reality’s thick veil.

Ultimately, the Russian Pavilion is a story, told in broad strokes, with a happy ending, a story typical of the official culture’s posters. Its quivering outlines lead us to conclude that the way Russia has been represented at the 2017 Venice Biennale reflects the Culture Ministry’s attitude to contemporary art. On the one hand, there is something like an attempt at dialogue. Otherwise, we would have been treated to three rooms of student sketches. On the other hand, for the time being, the substance of the dialogue resembles muttering more than robust debate: many topics are off limits, and we have not learned to talk about the rest. At the same time, I would like to hope the dialogue will be resumed at the next biennale. If that happens, then the government’s feeling of creative confusion is not such a bad thing. Under the current political circumstances in Russia, power’s attempts at dialogue tend to end in self-confident monologues, or much more fatal consequences. And perhaps it is a good thing that the occupation of three positions by a single official can be seen to be an impossible task, despite all references to the “Renaissance man.”

Translated from the Russian by Thomas Campbell. An earlier version of this essay in Russian was first published on Colta.ru.

Nadia Beard, “Grigory Revzin fired as Russian commissioner of Venice Biennale,” Calvert Journal (April 2014), https://www.calvertjournal.com/news/show/2251/russian-curator-grigory-revzin-fired-from-post-at-venice-biennale.

Interview with Semyn Mikhailovksy, The Art Newspaper Russia (March 2016), http://www.theartnewspaper.ru/posts/2831/ (my translation).

https://ifonlyyoucouldseewhativeseenwithyoureyes.com/.