The flourishing of South Africa’s commercial galleries over the last two decades has coincided with the atrophying of infrastructure, collections, and curatorial programs at the country’s major public museums. State neglect, hobbled budgets, and poor leadership at the South African National Gallery in Cape Town, as well as important municipal museums in Johannesburg and Durban, have resulted in, among other things, the ceding of curatorial narrative to the marketplace during the post-apartheid period. Over the last decade and in the absence of competition, retail enterprises like Goodman Gallery, Stevenson, and Whatiftheworld/Gallery have all staged ambitious group exhibitions mobilized around worldly themes that have served to introduce artists like Karo Akpokiere, Stan Douglas, Glenn Ligon, Julie Mehretu, Paulo Nazareth, and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye to a South African audience. For all their mobility and capital, commercial galleries also work within a system of constraints, with worldliness often shrunk to fit a partisan narrative.

“the silences between” typifies this history. Taking its title from a 1982 book by New Zealand author Keri Hulme, Goodman Gallery curator Emma Laurence’s feminist-inflected exhibition explores what Hulme described as “the writing of history and what is left out.” Her exhibition is, however, wholly made up of Goodman Gallery artists, including Candice Breitz, Kendell Geers, David Goldblatt, Samson Kambalu, William Kentridge, and Mikhael Subotzky, which complicates Laurence’s ambition to explore absences and lacunae in dominant narratives. Despite the prescribed frame of her show, of having to work in-house so to speak, Laurence successfully manifests her working concerns, largely through the contributions of Tabita Rezaire, a Johannesburg-based French artist of Guyanese and Danish descent, and Grada Kilomba, a Berlin-based Portuguese artist whose parents are from Angola and the West African island state of São Tomé and Príncipe.

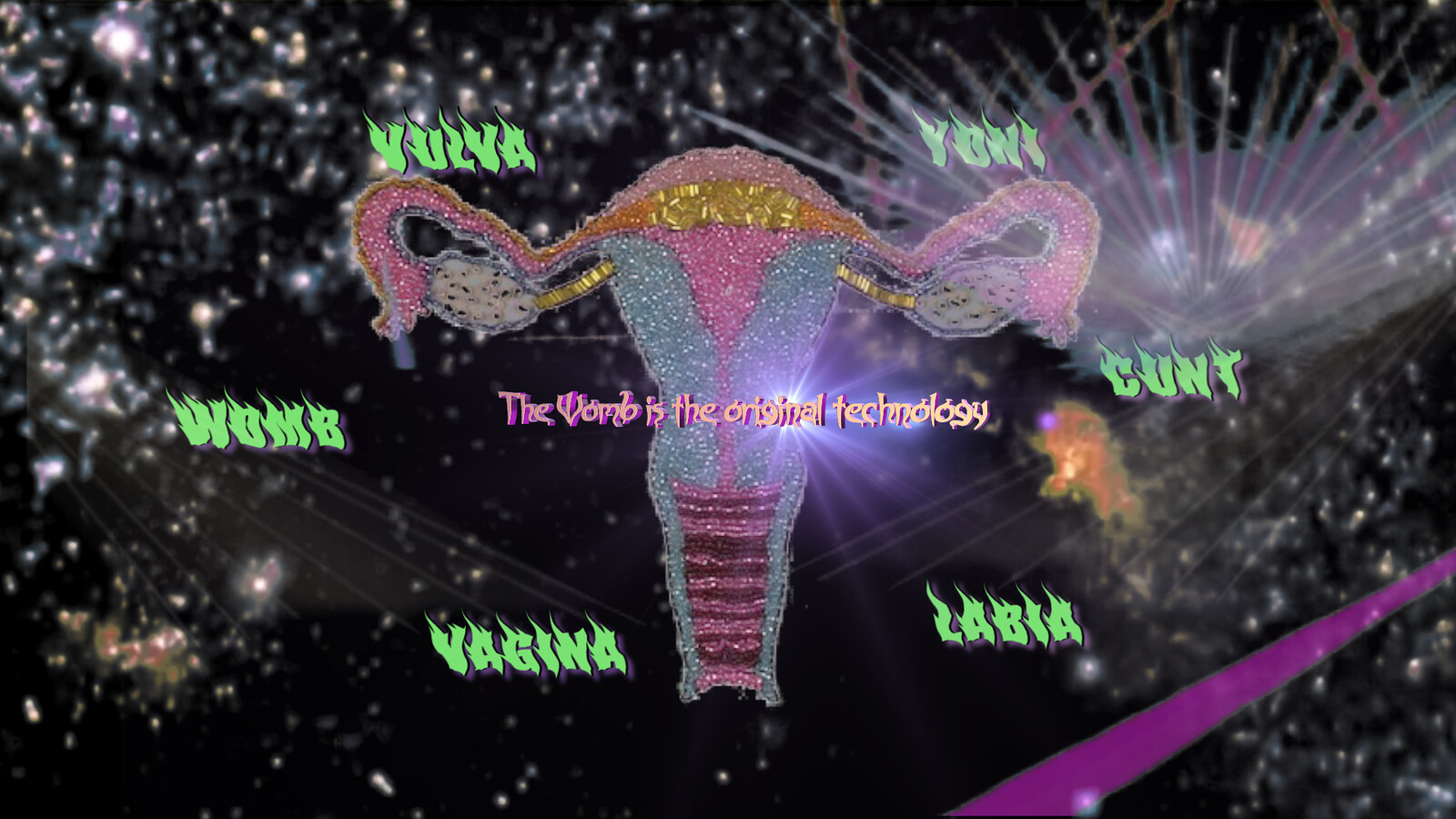

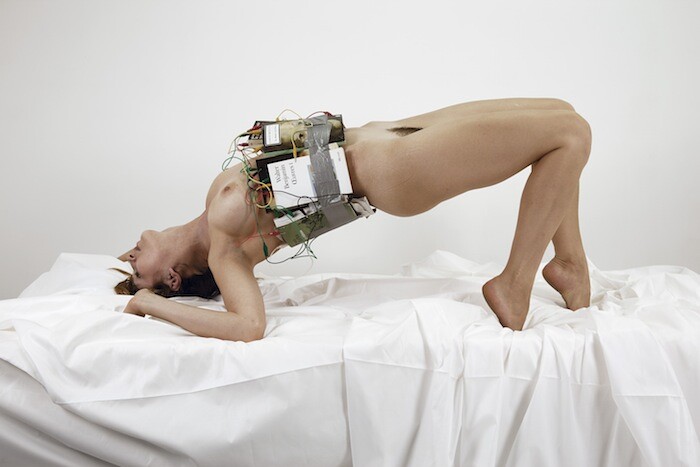

Composed of a pink gynecological chair and video monitor, Rezaire’s installation Sugar Walls Teardom (2016) is an affirmative piece of social criticism aimed at reclaiming the female anatomy. “The womb is the original technology,” as Rezaire puts it in a title overlaid onto the video’s narrative. Rezaire’s film is a confident showcase of her lo-fi digital filmmaking technique, here yoked to a feminist theme. Tracey Rose and Dineo Seshee Bopape, expressive artists who share similar social concerns and a commitment to the handmade in their films, are predecessors; fittingly, the exhibition includes Rose’s The Cunt Show (2007), a two-channel film based on a sock-puppet parody of artists questioning the narrow racial frame of “Global Feminisms,” a 2007 exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum that included Rose.

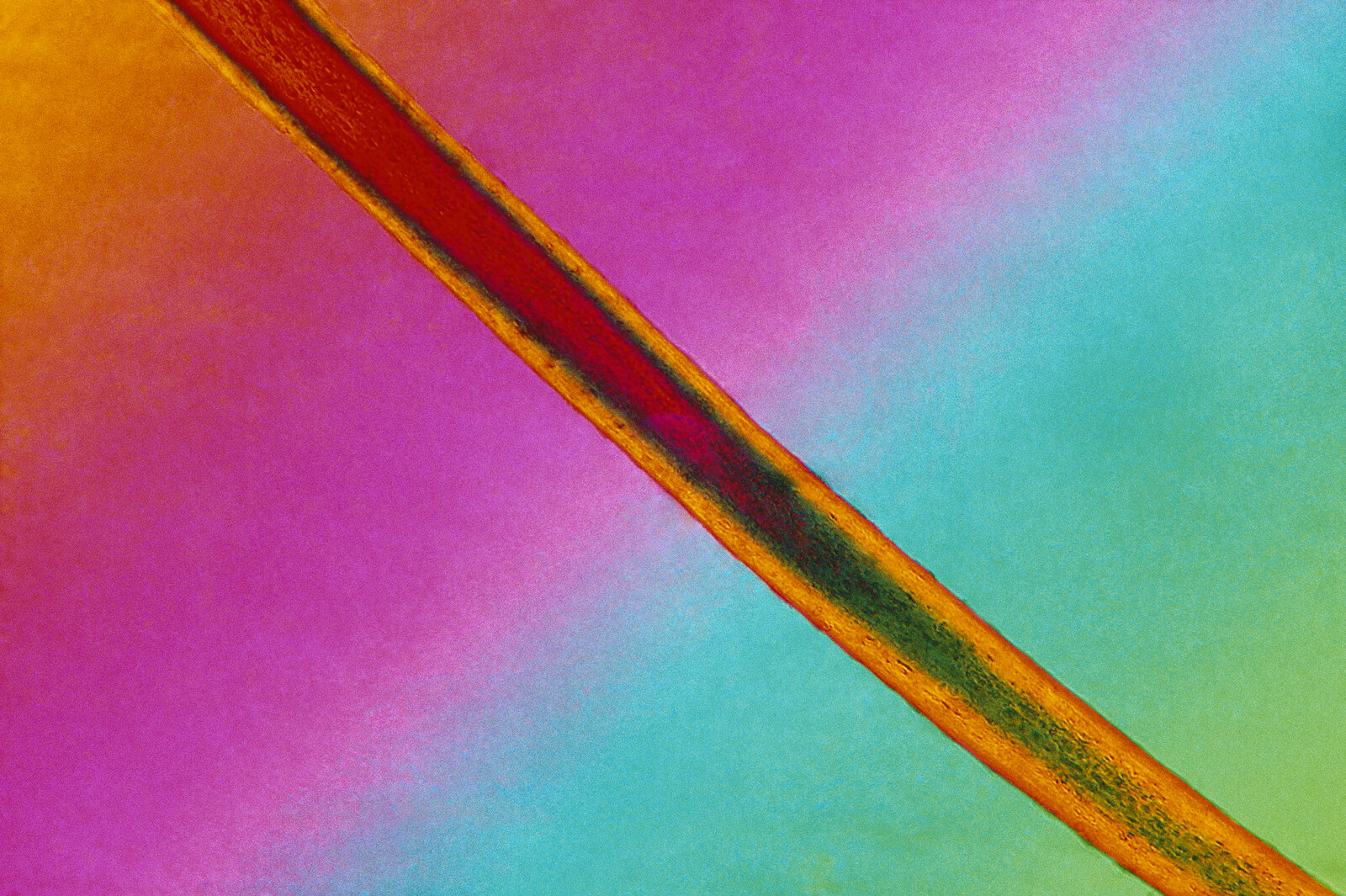

Sugar Walls Teardom includes a deliberation on American physician James Marion Sims, the so-called “father of modern gynecology” whose statue on New York’s Central Park was recently picketed by activists—Sims performed experiments on enslaved African-American women as part of his research. This grim historical detail is amplified by the installation adjacent to Rezaire’s work of an eye-tingling jacquard tapestry produced in 2015 by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, entitled Trace fiber from Freud’s couch under crossed polars with Quartz wedge compensator (#2). The tapestry presents a magnified forensic image of a thread from the psychoanalytic couch that became a site of patriarchal invention about womanhood. Rezaire wants to reclaim the female body and psyche from its containment by male-dominated western medical science. The film ends with Rezaire, a yoga teacher, leading a restorative meditation on the womb.

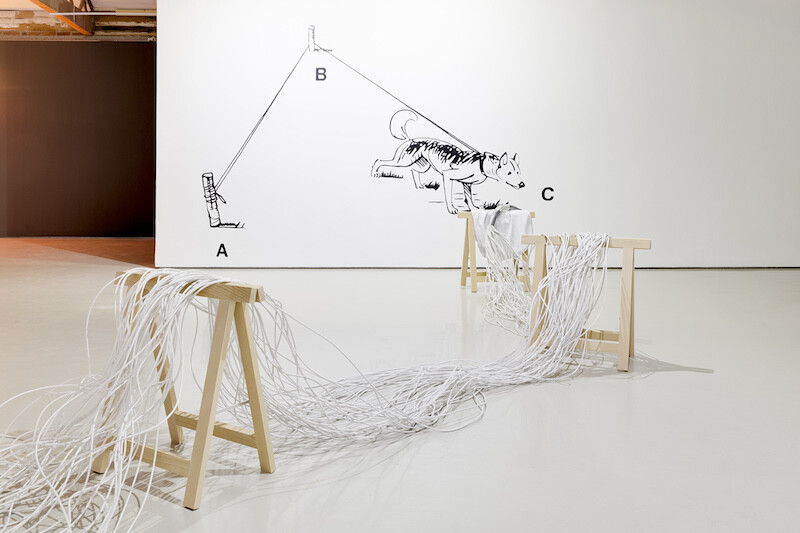

In her dual-channel film, Illusions (2017), Grada Kilomba narrates the Greco-Roman myth of Narcissus and Echo. An update of a lecture-performance premiered at the 2016 São Paulo Biennale, the action toggles between Kilomba, who plays the role of narrator-interpreter seated on wooden chair, and three actors—Martha Fessehatzion, Moses Leo, and Zé de Paiva—performing on a mostly bare stage. “I was invited to come here, but there is nothing new I can say,” explains Kilomba, whose image appears on a television screen obliquely placed in relation to the main projection. “We know everything but just tend to forget it.” Kilomba often pauses to watch the action on the larger projection. Her actors, their costumes made of plaid plastic fabric, sit, lie and also cavort to the song I Put a Spell on You, both the original 1956 version by Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and Nina Simone’s gravelly 1965 cover.

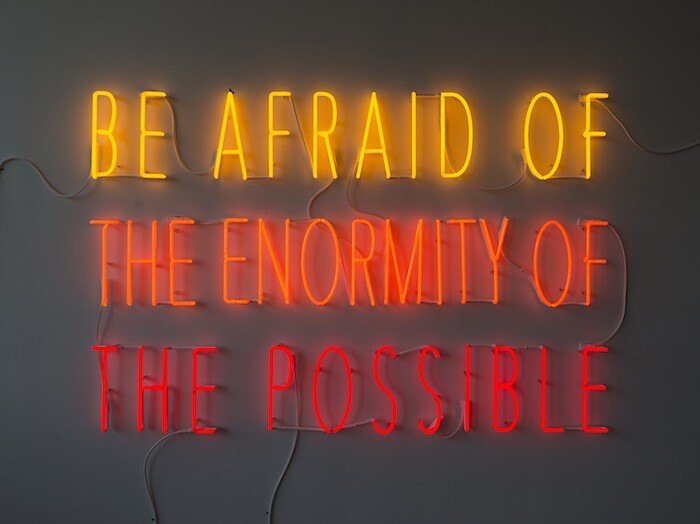

As the film progresses, the narrative shifts from creative retelling to incisive interpretation. “All this whiteness that burns me,” says Kilombo, quoting Frantz Fanon in Black Skin, White Masks (1952). In the story of Narcissus and Echo, offers Kilomba, truths of the white patriarchal system are revealed: its absorption with reflected images of whiteness and persistent immersion in “multiple layers of ignorance.” Alfredo Jaar’s neon text piece, Be Afraid of the Enormity of the Possible (2015), appears alongside and is fitting as an introduction to Kilomba’s work; as a standalone work it offers little more than immanent prophesy on an unknowable future. A nearby figure drawing by ruby onyinyechi amanze, You’re too fly, not to fly [S.W] (2016)—depictions of dancers and free-floating heads on a largely unmarked sheet of paper—reiterates the blank space negotiated by Kilomba’s actors in her compelling parable of whiteness.