Walking home at night, I pass by Campaign (1972), a two-channel video installation by Ferdinand Kriwet projected onto the storefront windows of Georg Kargl Fine Arts. In the dark street, the images of television footage from the 1972 US presidential campaign fronting Richard Nixon and George McGovern are silent; at the gallery during the day, they almost disappear against the light, but the field recordings, collected by the artist on a trip to the US to witness the primaries, are audible.

The sound of talking heads and debates shapes the experience of the exhibition, a last remnant still on view from curated by_Vienna, a festival inviting international curators to organize fall exhibitions in the city’s galleries. The theme of this year’s iteration was language in contemporary art, and curator Gregor Jansen honed in on the 75-year-old German artist’s longstanding interest in media and focus on text and dissemination. These are crucial issues in our divided societies, in which it is inconceivable that any candidate could win a landslide like Nixon’s (who won 62 per cent of the vote, taking every state except Massachusetts and Washington DC). Jansen did not need to spell out a connection to contemporary politics: speech and its relationship to images is a defining problem of our time.

Who is speaking—and who gets to speak—is a conversation that stretched throughout 2017, from Hannah Black’s open letter to the curators of the Whitney Biennale about Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till (Open Casket, 2016) to #metoo and the awe-inspiring snowballing of charges made by those emboldened to stand up to their abusers because others did before. At Elisabeth & Klaus Thoman, the work of German photographer Jürgen Klauke is proof that the “right” credentials do not necessarily connote sensitivity. Klauke, who made a name for himself in photography, performances, and body art works that explored identity and gender using his own body, presents series of drawings that are even more overtly sexual than the 1970s self-portraits in sexy, androgynous outfits for which he’s famous. At the gallery, series like the twenty-eight ink-on-paper drawings “Körperzeichen – Zeichenkörper II” (2012, translates loosely as “Body Signs – Signs Body”) include an image of a black bare-chested woman looking up in anguish and another drawing of a black woman whose hair forms the shape of testicles. No amount of self-exploration in the past, no amount of gender-bending, can make this ok.

Solidarity is to be found elsewhere in town. Viewers entering contemporary art museum 21er Haus walked over the floor plan of the Museum Morsbroich in Leverkusen, Germany, from which this exhibition “Duet with Artist” traveled. The work is a version of Mischa Kuball’s leverkusen_transfer (2017), in which the German artist placed a large sheet printed with the floor plan of the Morsbroich space in front of the city hall. It was spread there for three months, exposed to the elements and the footprints of passersby, then brought into the museum, snugly fitting its floor. In Vienna, the same floor piece becomes a trace of absence, or of the possibility of absence—last year the city of Leverkusen suggested the Morsbroich be closed and its collection deaccessioned to pay for the museum’s financial difficulties—as one institution aligned itself with its struggling partner.

“Duet with Artist” was organized as a way of pointing out the importance of an institution to its audience. It includes Rirkrit Tiravanija’s ping-pong tables emblazoned with the words “tomorrow is the question” (Untitled 2015 [MORGEN IST DIE GRAGE], 2015); a new Hans Haacke survey including questions like, “Do you think your government is doing enough for refugees?”; Yoko Ono’s Mend Piece (1966/2017), in which you’re meant to sit at a table, use superglue and tape to fix broken crockery, and think about mending the world as you do it; Wish Tree (1996/2017), a station set up by David Horvitz with paper and German and English stamps that can be used to write poetry (I wrote a monolingual poem about snow and oceans); and a bar made by Claus Föttinger, complete with free coffee, a jukebox, and a vending machine selling one euro bottles of Becks, all allowing visitors to play, talk, interact, and think about how they come together in public spaces.

The 21er Haus exhibition was billed in the Viennese press as a weekend activity for children, which is fair enough considering the ping-pong, drawing, and cutting-and-pasting done in the space. More sophisticated exhibitions of participatory art explore the meaning of participation rather than simply offer it up, but as museums struggle for funding and recognition, these two institutions stand in solidarity to insist on the role of culture in society by staging an exhibition that exemplifies how viewers engage with it. It’s one answer to the question of what our public institutions do. Another answer is put forward by Thomas Bayrle’s solo exhibition at the MAK, the Austrian Museum of Applied Arts, for whose great columned hall he has created a new work, as well as an exhibit of works dating from the 1960s to 2017. Bayrle’s work in tapestry, prints, fashion and industrial design, photography, and sculpture corresponds to the pieces in the museum’s collection—furniture and applied arts, jewelry, posters from turn-of-the-century Vienna—in a way that sheds light on both. Tools, objects, pattern, and design raise questions that run along the history of making, and this exhibition looks to enhance the understanding of the institution’s collection and the contemporary work by bringing them together and linking them up.

Two gallery exhibitions also consider art history, Andy Boot’s “Smart Sculptures” at Emmanuel Layr and Angelika Loderer’s “Quiet Fonts” at Sophie Tappeiner. Boot’s solo show includes two sets of works: paintings using “Black 2.0,” an acrylic paint promoted as the blackest black possible, to paint over texts theorizing two blockchain projects (White Papers, 2017) and 3D-printed sculptures made of an amalgamation of files. Resting on plinths, the sculptures look like modernist pieces (the press release mentions Barbara Hepworth) but where a modern master would sculpt by chiseling and carving from a material, Boot’s work is a process of addition. Down the street, Loderer is presenting sculptures made of metal and sand. Like arms, they hang from the ceiling above a floor covered with black sand. Entering the gallery is like moving into a grim and musty vision of the future—in which organic matter is foreign, distant, almost unrecognizable—but the work also brings to mind other sculptural examples and references, from Arte Povera to Miroslaw Balka.

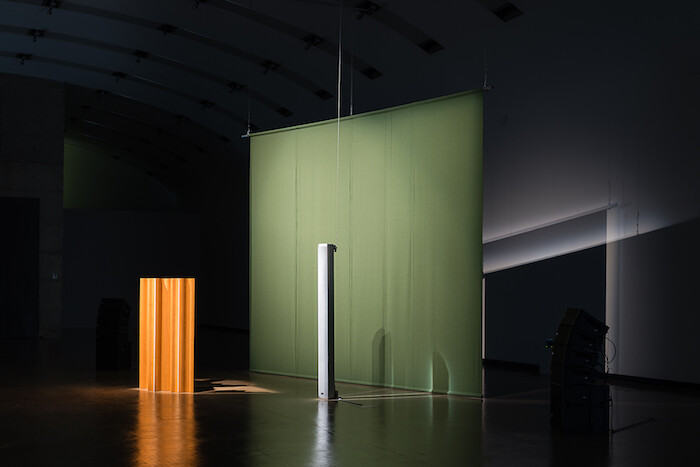

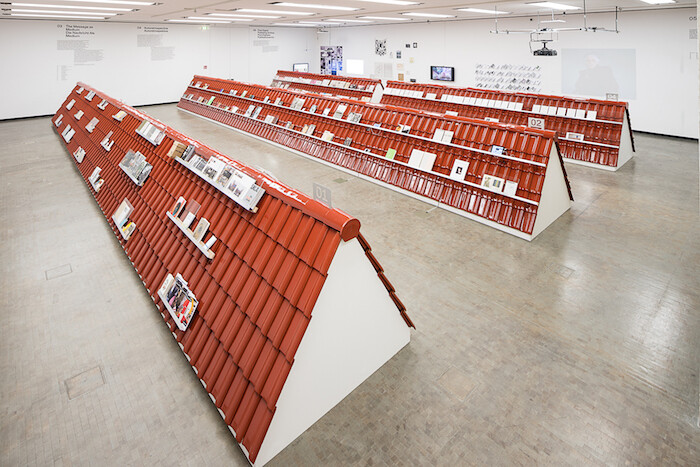

But the connection to art history needn’t be only object-based. At Kunsthalle Wien, Florian Hecker presents “Hallucination, Perspective, Synthesis,” an exhibition consisting of three sound installations that fill the space while still allowing the visitor time and space to think—to experience the work by walking through it, and feel a certain liberation from expectations of how to respond to sound and music. At a live performance by Hecker on the opening weekend, two librettos by theorist Reza Negarestani were performed, though the text was never fully clear. Presented in a theater setting, it confirmed that the real potential of the work is in the freedom it allows listeners to wander through it. Also at Kunsthalle Wien, the exhibition “Publishing as an Artistic Toolbox” presents selections of books made by artists, a large number of art magazines started by artists, a small retrospective of artists’ interventions in newspapers and periodicals (from Group Material’s Aids Timeline, 1989, to Hans-Peter Feldmann’s issue of Profil magazine, 2000, scraped of all the texts), and a section dedicated to publishing after the digital. This well-researched show could be reconstructed by other institutions—hopefully without the overwrought exhibition design in which the print projects were presented on brick roofs—by sourcing the same books from different collections, challenging the museum’s role in reifying the objects it presents.

Our relationship to what institutions reify can always be reassessed. At the Secession, R.H. Quaytman and Olga Chernysheva both present friezes, a response to Gustav Klimt’s famous Beethoven Frieze (1902) in the building’s lower level. Quaytman’s site-specific project begins with two paintings by Flemish artist Otto van Veen and responds with a series of her own, presented along the lengths of two temporary walls which meet in the middle of the exhibition hall. Though Van Veen’s paintings are in the Kunsthistoriches’s collection, they are rarely on view and his work was largely forgotten except in relation to his most famous student, Peter Paul Rubens. Quaytman tackles paintings featuring sexualized female imagery, which, abstracted and expanded by a female contemporary artist, acquires a new strength and sense of agency.

A sense of slowed-down time permeates Chernysheva’s “Chandeliers in the Forest.” In it, a small frieze, Queuing (2017), is made of drawings of horses’ legs, framed and hung along the staircase. The exhibition also includes paintings of bathers in a river in Moscow that has dried up due to global warming, and two lightboxes of chandeliers hanging from wooden poles on a country road (On the Sidelines, 2010). The story goes that when a glass factory couldn’t afford to pay its employees, it gave them the products of their labor; one worker hung the chandeliers there in an attempt to sell them to passersby. It’s a work of wonder and desperation that hovers on the border of the sentimental and comes back clear. It is rescued by Chernysheva’s special brand of attention, heavy on narrative and served up with poetic, beautifully written texts. It’s hard not to be charmed by it, not to look at it and see a light in dark times.