“Found in Translation” is a quiet exhibition that exudes a palpable sense of yearning for a past that never quite was. Golnar Adili’s childhood was shaped by the fracturing of her family due to political events; born in Virginia, she returned with her parents to their home country of Iran in the wake of the 1979 revolution. Her father, a leftist activist, soon returned to the United States, forced into exile by his political convictions. The exhibition is an expansive yet cohesive “lexicon of displacement” (in Adili’s words) articulated through a floor installation, sculptures, digital and silkscreen prints, and photo lithography.

The first piece we encounter is She Feels Your Absence Deeply - Pixels (2017), a digital image of the artist and her mother printed on delicate Japanese paper and reconstructed in a grid of quarter-inch wood cubes reminiscent of children’s building blocks. The two subjects, seated close together, stare directly at the camera with gravitas, intent on capturing the moment, no matter how joyless. Titled after a line in a letter from Adili’s mother to her husband, in which she describes their daughter’s visceral response to the family’s disintegration, the piece evokes many of the exhibition’s essential themes; the (re)construction of memory, the (futile) attempts at childhood play and distraction, the ever-present void left by her father’s prolonged absence. In a more recent rendition, She Feels Your Absence Deeply (2021), Adili further mines her father’s archive, a chronicle of their years apart, creating a portfolio box that unfurls to reveal a set of blocks with images printed on all six sides. The initial picture is set alongside two passport photos, in which the artist’s mother is visibly altered by the years of separation from her husband, as well as reproductions of her letters to him, and the plane ticket that enabled his flight from Iran. The audience is invited to view the family’s intimate history in the form of a children’s game, altering the combinations, exposing and concealing the details, never able to see the whole picture in this narrative of fragmentation.

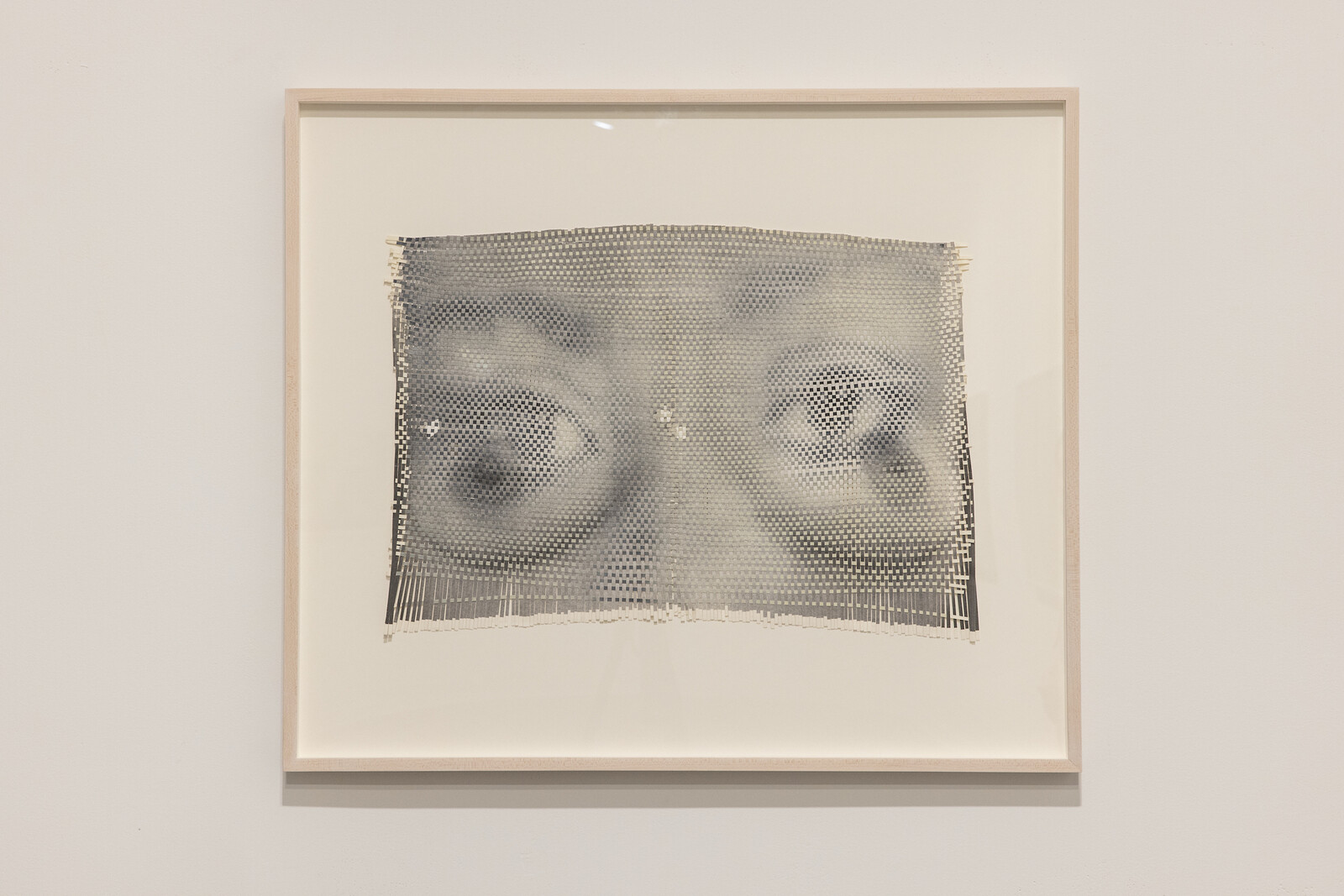

The father’s absence-presence is perceptible throughout; his specter haunts the space, appearing briefly in ephemeral photographs and fragments of letters. By contrast, the artist’s mother is a powerful presence, her photographs emanating stoic resilience. My Mother’s Eyes (2018), a photocollage that hangs on the back wall of the main gallery, watches over the space with vigilance. In My Mother’s Eyes Woven into My Chest (2018) her eyes are intertwined with the artist’s body like a protective amulet, further underscoring the intimacy between the two.

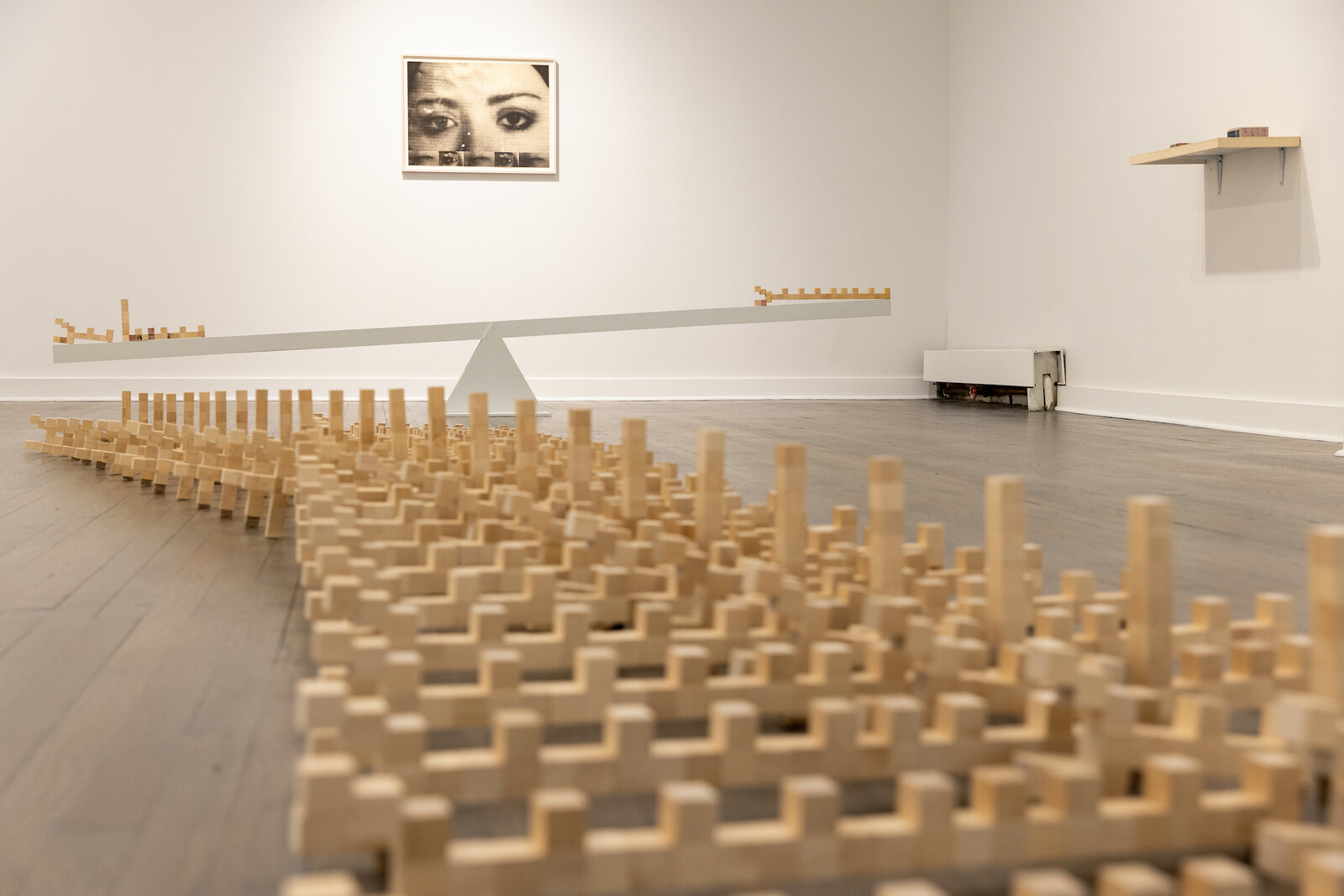

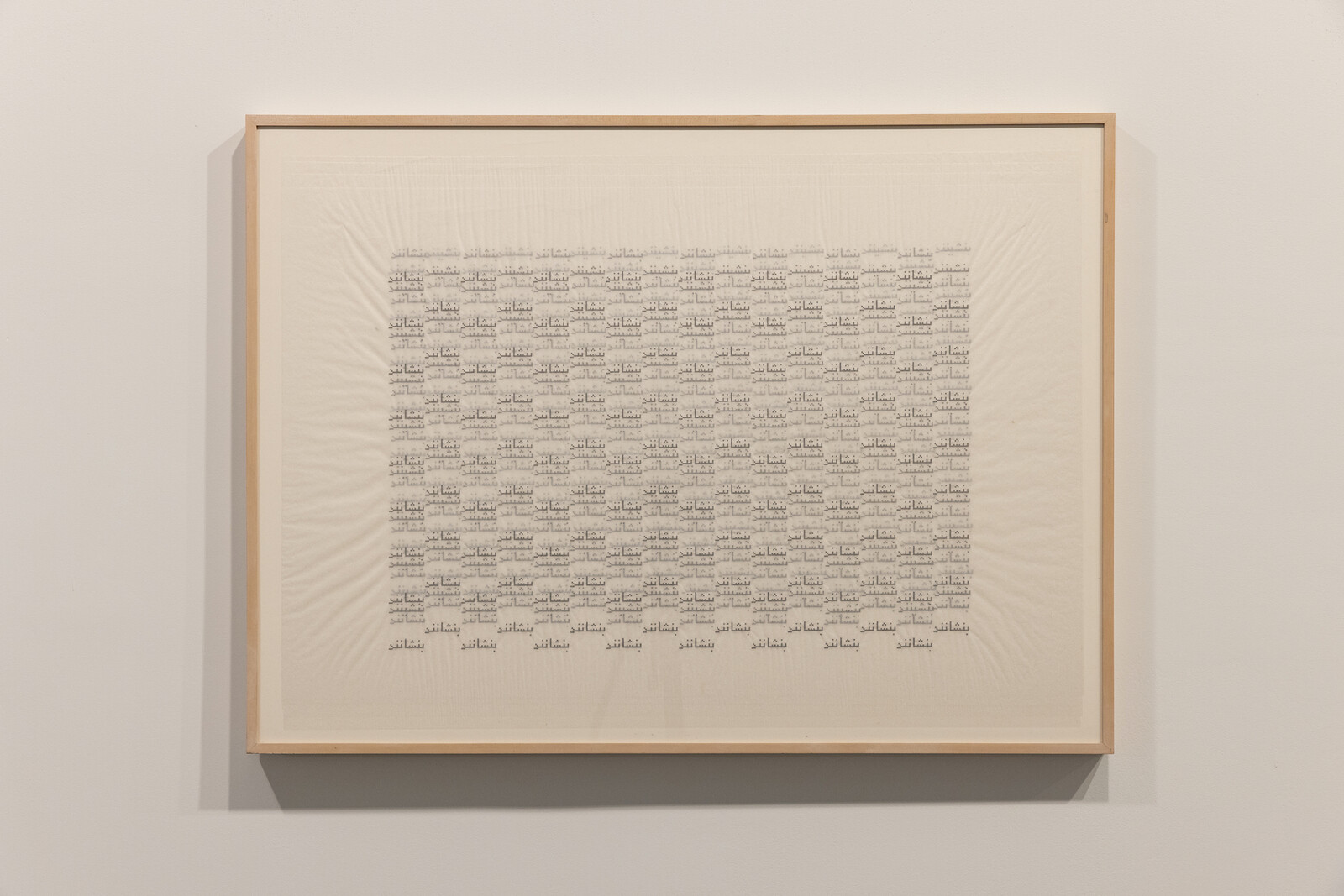

Adili’s engagement with language, especially Farsi script and Persian poetry, takes different forms throughout the show. Her exploration of Samanbouyan [The Jasmine-Scented Ones], a poem by the fourteenth-century poet Hafiz, began in 2008 with a graphite drawing in which she focused on the opening verse, transcribing it in pixelated kufic script. The repetition of the verbs at the end of the verse create an hourglass, a form that continues to reverberate in Adili’s later works. She translates it into a three-dimensional resin print in As They Sit They Settle (2018)—the letters fading in and out, gaining greatest clarity in the middle, where the verb repetition is most frequent—and again as a large floor installation, Benshinand Benshaanand (2021), comprised of wood pieces, a nod to Adili’s background in architecture and her playful fascination with children’s puzzles.

Repetition of text and form emerges as a meditative practice in Adili’s work. In a series of silkscreen pieces, she contemplates the tension implicit in the pairing of the verbs benshinand [they sit] and benshananand [they settle] as they appear in Samanbouyan, combining alternating printed sheets of each verb and fixing the two into a relational pattern reminiscent of geometrical embroidery. In an earlier set of collages, she isolates dismembered arms and hands and arranges them in repeated configurations on graph paper as they “embrace” and interlock. These pieces highlight the importance of rhythm and return in the lexicon Adili is intent on generating; through the constant process of revisiting, she strives to render a complete picture from an archive constructed through absences.