In June 2021 Urs Fischer exhibited “The Intelligence of Nature,” a group of paintings made during a year when Fischer, like many, was forced to spend more time at home than normal. After artists’ and curators’ immediate—and sometimes kneejerk—responses to the Covid-19 outbreak have passed, and as we discover the pandemic will be a permanent reality of global life for years to come, as well as a symptom of deepening ecological and economic crises, more considered art can offer us a guide to this new situation. And one thing recent painting might be able to do, as a practice for reflecting on the pressures of our new present, is give us a sense of how these interlocking crises—as Fischer’s series suggests—are shaping our experience of time. A “crisis,” after all, is a temporal phenomenon: a decisive turning point that changes our understanding of what went before, and our experience of what will come next.

In Fischer’s paintings, the background images are primarily photorealistic depictions of scenes from his house in Los Angeles, which appear to be covered in smears of paint, at times so dense they cover the whole canvas. On close inspection, however, the relationship between these component layers spirals into something more complex than background and surface, a source and its defacing. Gnarly Guard (2021), for example, shows a green cactus outside the windows of a wooden home, with this image encrusted with thick blobs of paint. The palette of the background image seems to have been Photoshopped by someone on acid: the walls of the house are canary yellow, the window blinds baby pink, the grass burning orange. The crusted smears rework these colors in the medium of thick oil paint. But coming right up to the surface, these craggy folds of paint reveal themselves to have no depth: the entire picture is a screen print on gesso finished with epoxy primer and mounted on an aluminum panel.

These works could be seen as yet another instance of contemporary painting responding to historical crisis by self-reflexively investigating its nature as a medium: the tension between gestural mark and the mechanical rendering, the relationship between painting and other media of representation. For critics as different as Clement Greenberg, Rosalind Krauss, and T. J. Clark, this is the story of painterly modernism itself. Contemporary discussions of painting’s relevance have again circled back to the question of medium specificity, as if the way to provide an answer to the question “why make a painting?” is to first answer “what is a painting?” Yet in an attempt to move reflections about painting’s relationship to other practices beyond the question of medium, David Joselit has proposed an alternative “definition of modern painting’s specificity: it marks, scores, and speculates on time.” In the work of contemporary artists working with painting now, the question of “what is a painting” seems less fruitful to explore than a different one: when is a painting?

We might then see Fischer’s paintings not only as being about painting’s relationship to digital manipulation, but also as a reminder of how distended in time the production of any painting can be. Copying a source, mixing colors, making gestures, layering impasto—and, not least, letting it all dry. These temporal distensions always require technical media: brush, pigment, screen printer. To distinguish between the brush and the laptop on the basis of an analogue-digital divide prevents us from seeing one way that a painting’s dispersal in time can capture distinct aspects of digital images. Unlike a painting, which moves from liquid to set, a digital image can be always manipulated. To risk some jargon, painting’s dry ontology can help us better grasp the digital object’s liquid ontology.

If digital images are liquid in the sense they can always be changed through being reprogrammed, they are also liquid in the way they flow around information circuits and networks. Ever since at least the rise of Pop Art, this has been one way in which painting has responded to mass-media imagery. As Hal Foster has written, painting in the 1960s found a new role as a kind of “meta-art, able to assimilate some media effects and reflect on others precisely because of its relative distance from them.” Again, however, the source of painting’s criticality is an anxious competition of difference—art vs spectacle, painting vs photography—that can paralyze many artists’ engagement with media images. Thinking of painting less as a medium than a way of dealing with time, in contrast, can allow the time scored into its creation to flow into and out of digital media’s circulation of images.

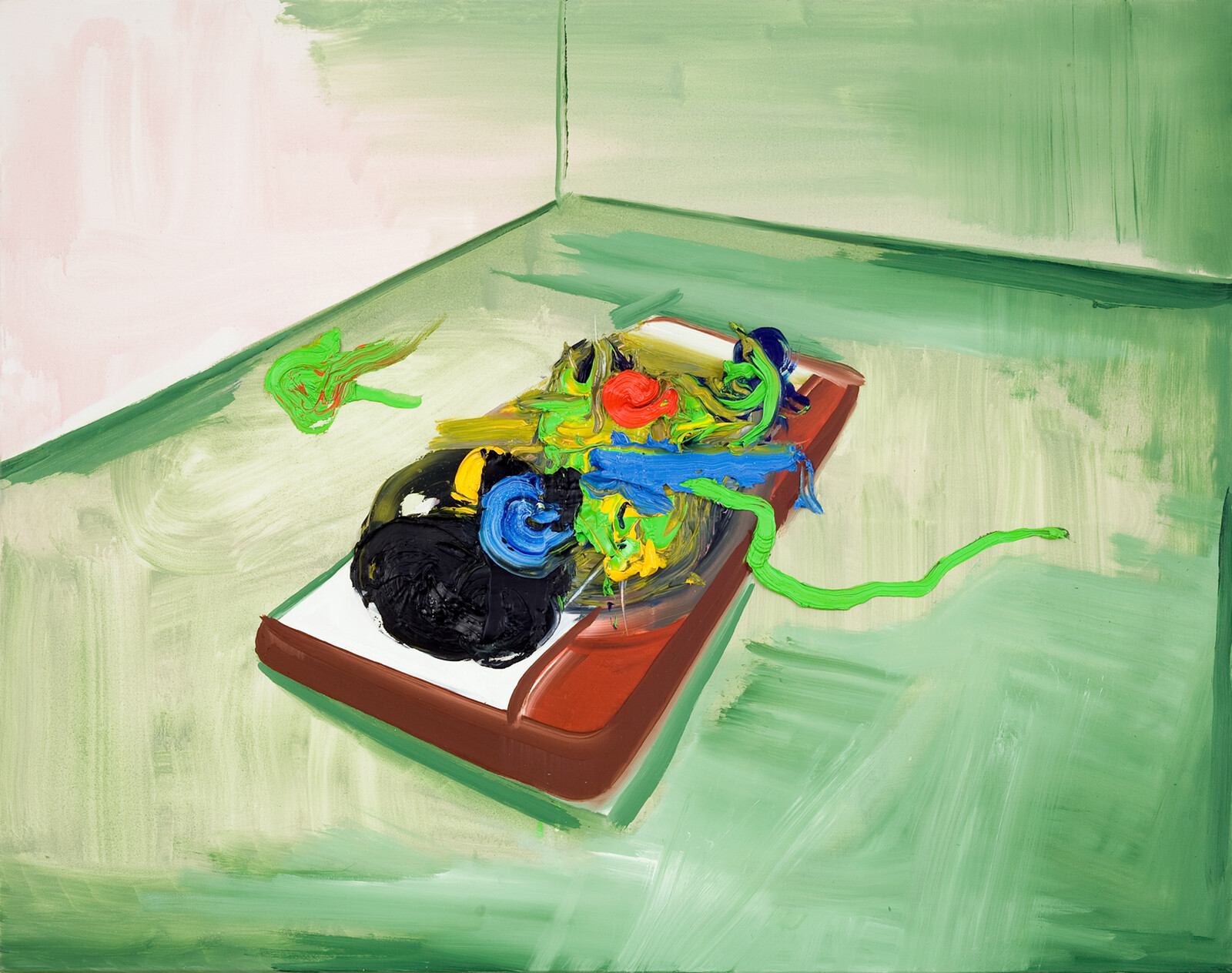

In 2011 Wilhelm Sasnal made three paintings based on images he found online of the death of Muammar Gaddafi: Gaddafi 1, Gaddafi 2, and Gaddafi 3. The first shows a mattress in a green room, where in place of Gaddafi’s corpse are piles of oil paint, almost an inch deep: black, blue, green. We don’t see a dead body made into a spectacle, we see matter that has changed over time, irreversibly, from liquid to solid. The third image in the group shows the corpse, but from a stark angle: the feet occupying the foreground, the body stretching behind. In this, the reworking of the source image recalls the drastic foreshortenings of Christ’s body by Mantegna. That painting can draw on, rather than be crippled by, its history is also a feature of Marlene Dumas’s Stern (2004), a painting of the photograph of the dead Ulrike Meinhof that was already the source for Gerhard Richter’s Tote (1988). A strategy of reappropriation brings us into the temporal flow of media images, rather than giving us a space of critical distance. Dumas’s facture is not the same as Richter’s—the repainted photograph reveals that the recurrence of imagery across different media platforms is not the stasis of repetition, but the developing process of variation.

The “when” of a painting is always also its position in the history of the practice: both its burden and the source of its temporal complexity. But those histories aren’t fixed. Painting can model approaches to time that can rewrite histories of art. Anna Plesset’s Value Study 1: A View of the Catskill Mountain House / Copied from a picture by S. Cole copied from a picture by T. Cole / 1848 (2020), presents an unfinished copy of a painting by the Hudson Valley painter Thomas Cole, which was itself a copy a painting by his sister, Sarah Cole, who along with many women has been erased from standard histories of the movement. Taped to the canvas is a smaller trompe l’oeil oil copy of a Google image search of Sarah Cole’s painting, as if to suggest that this is the model for the unfinished copy in progress. A “painting” is broken down into component processes of drawing, copying, and digitally mediated research. That these don’t have to be linear, or progressive, enables a similar recasting of art history.

Yet painting can also be a reminder that while it is not linear, the time of human life is finite. In summer 2021 Walter Price exhibited the paintings he made during the first lockdown in New York at Camden Arts Centre in London. When it began, Price decided he would only use what materials were left in his studio. Whether a series of black drawings of human figures, or compositions in his own abstract language on fields of white, every mark in these works is a record of material running out, of a time coming to an end. But also, as happens when time slows, with a strange sense of expansion and plenitude. In a group of color-field paintings, thinned-out pink and thin green break as they are stretched across a canvas. In the muteness of exhaustion and things coming to an end, it can be a gift to discover we no longer know what is coming next.