The summer of 2018 was grifter season. Starting sometime in May, a strange coterie of glittering personages came coasting along: hustling socialites, scurrilous aventuriers, faux–Saudi princes. The hoax has always had a special place in American mythology, from a newspaper editor convincing his readers there were unicorns on the moon in 1835 to P.T. Barnum’s unveiling of an exotic mermaid in 1842, but there seems to be a renaissance in a present-day America where the sociopolitical order feels like it’s crumbling. And these swindling apparitions with the power to dupe the richest among us (think of Anna Delvey, a young Russian woman reborn as a German aristocrat in New York City[1]) have the gleam of folk heroes.

The anonymous performance artist who goes by the name of Zardulu the Mythmaker has a keen understanding of this bunk that resides at the heart of the American imaginary. It’s the fundamental stuff of her work: she crafts an outlandish con, then tips off a credulous media outlet, and sees it go viral. The work is over when the artist chooses to trigger the reveal—the gotcha moment that shows everyone what a fool they’ve been to believe. (It can take years to come, if at all.) Pranks like the Pizza and Selfie Rats and the three-eyed catfish of the Gowanus Canal were Zardulu-authored, and have secured her a place in pop culture and urban lore over the past few years.

Zardulu’s first gallery exhibition, “Triconis Aeternis: Rites and Mysteries,” came a little late for grifter season. The political landscape was even grimmer in the fall, as the country braced for the inevitable confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh. The question of what each of us believes in had become political in a desperately cutting way and a room full of mediatized tricks sounds glib against that backdrop. Walking toward the gallery, you see a huge screen propped up by the window playing a digital collage of Zardulu’s madcap hits, including screenshots of stories splashed across prestige outlets like the BBC and the New York Times, as well as the trashier Fox and New York Post. Oh, fake news. Is demonstrating how easy it is to get a story published and set up for going viral necessary in 2018?

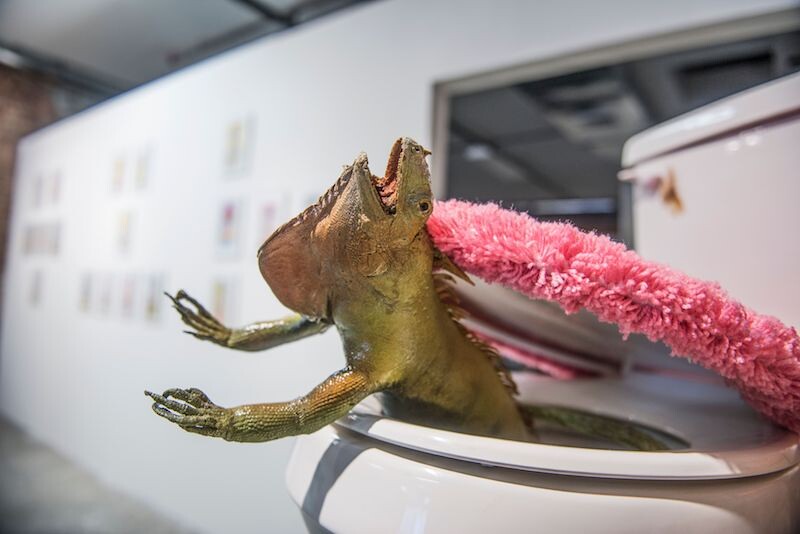

It’s possible that Zardulu’s bamboozlements were not only litmus tests of media gullibility, but also of viewer cynicism. I wasn’t predisposed to generosity, but still found myself strangely disarmed by the suite of seven arrangements of taxidermy animals scattered through the gallery’s main space. A bravely smiling raccoon sitting on their haunches atop a grinning alligator, swimming through the air above a simulacra of river weeds and lotus flowers (Shores of the Acheron). A honey-maned rooster with the butt end of a blunt in his beak swaying over a blank-eyed pigeon, who sports a crust of bread around their neck like a royal mantle (The Chasm at Delphi). A yellow-toothed beaver beaming madly as they clutch a prosthetic human leg, while a red-headed woodpecker flutters behind, struggling under the weight of the ferret on their back (Hegesistraus’ Sacrifice). (An eighth scene is covered in a black shroud—this hoax has been released into the wild, but its truth has not yet been revealed, the gallerist informed me). Some of the scenes are internet-famous, others less familiar, but they are rendered legible thanks to an accompanying hagiography: an online component to the exhibition that decodes some of the dioramas by presenting an archive of the original, Zardulu-produced “documentation,” the first news stories, and the animal characters’ transmogrification into meme-form once the story goes viral, as well as the date and source of “the reveal.” (The moment of the reveal is also the only date associated with the works—the actual start date of the tricks, whereas the manufacture of the sculptures themselves, is murky).

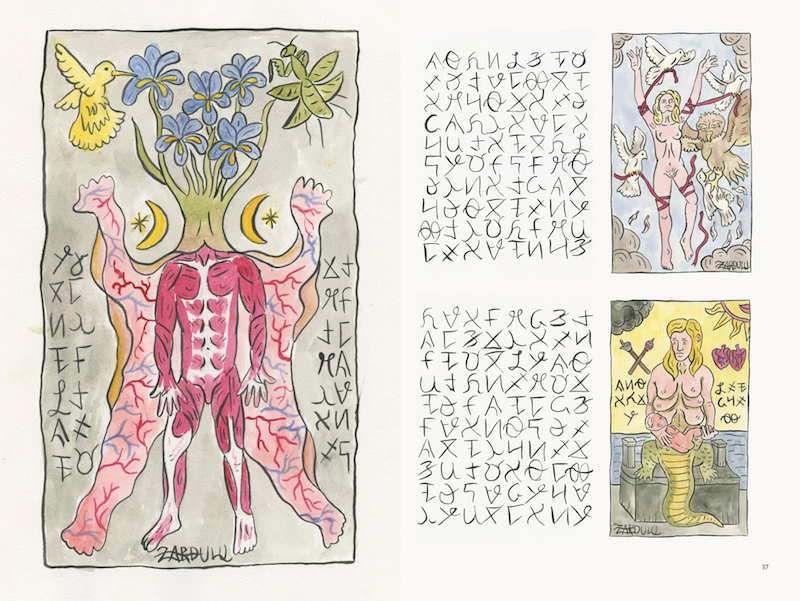

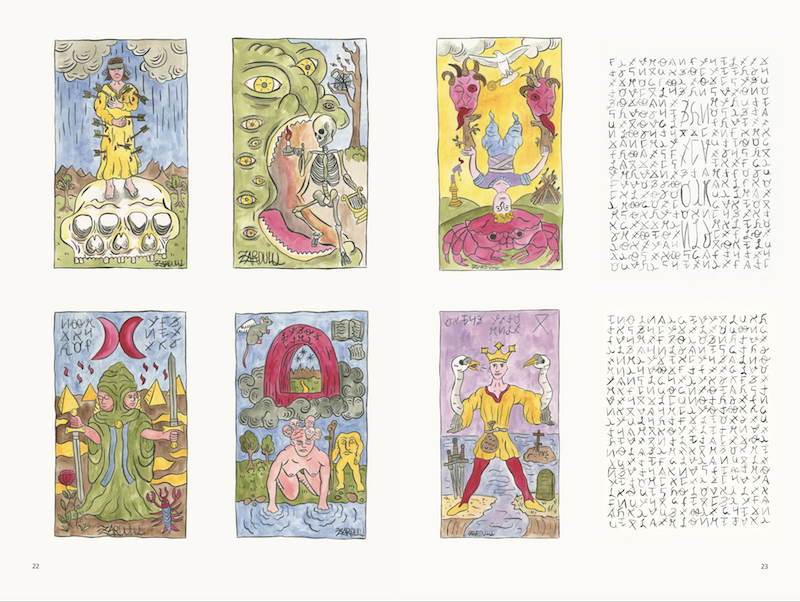

It’s all too self-aware to qualify as camp, but there’s an earnest and awkward bizarrerness to these stiffened animals that puts them on an emotional register somewhere between the crassness of Ripley’s Believe It or Not (with its shrunken heads and polycephalous goats) and the yearning wonder of the Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles, with its needle-eye-sized sculptures and decaying dice. But as opposed to the tradition of a pseudoscientific wunderkammer, Zardulu’s creatures have the aura of a medieval bestiary—a sense of dark, premodern magic that continues in her gouache Tarot paintings (six on black paper arranged on a shelf in the front of the gallery, 18 on white paper mounted on the back wall). These are humbler than the lunatic beasts, but similarly alluring, crafted with lucid lines and pastel colors, and suffused with a grotesque eroticism. Purple flowers sprout from a man’s flayed body, his naked musculature calmly leaning against a blanket of his spread-out skin, threaded with veins. A bare-breasted woman bursts from the belly of a buck whose intestines are draped over her outstretched arms. Strange glyphs (characters in a decipherable, Zardulu-invented language) appear in the corners.

It all combines to present a seductive universe that massages you into willing to believe. The animal-kingdom hoaxes traffic in the absurdly powerful pull of cuteness and strangeness, the two ingredients necessary for success on the internet; they can briefly make your heart swell with the excitement that such a brave if foolhardy raccoon could exist in the world.

But why the reveal? That gotcha moment produces the stupid laughter born of relief that you weren’t the one duped, and the anxiety that you could have been taken in; it’s a blade of meanness hidden in an otherwise cutesy endeavor. In interviews (Zardulu will appear to journalists from time to time, wearing robes and a golden mask) the artist has said she perpetuates these frauds to bring a little beauty and magic back into the world, but she is also preying on our current disorientation, and our desire to exercise faith in a world that might be near the end times, if the recent report by the UN’s panel on climate change is to be believed. She’s like the diddler that Edgar Allan Poe (himself a notorious hoaxer) wrote about—the audacious, ingenious trickster who grins alone at night.

I saw the exhibition before Kavanaugh was confirmed; I wrote this review after learning we’re 20 years away from environmental cataclysm. Zardulu’s hoaxes felt easier to believe than those oppressive realities. In his 2017 book Bunk, writer Kevin Young explains the staggering obsession with the hoax in nineteenth-century America as an infant nation trying to establish its own traditions and mythical past. Today, confronted by an ever-shrinking future, maybe we anxiously desire half-glimpsed mysteries like Zardulu’s in order to imagine the possibility of a beyond.