How can one write about Shuruq Harb’s work when the work itself is already a wonderful text about the potential of writing? At first glance, one could be fooled into thinking that the artist’s questioning of a dominant visual culture tackles its subject straightforwardly, through images, only to be surprised at how essential writing, text, and language are to the work. Not that they were ever separate to begin with.

The more one delves into “Ghost at the Feast”—Harb’s solo exhibition at Beirut Art Centre, comprising five video installations and sculptures made over the past decade—the more one understands that the images’ “duty” is to make the text appear, while the text pushes the image to the margins and slowly breaks its supremacy. What we hear or read in this exhibition is at the same time a caption, a poem, a press release, and a beautiful literary form.

This tense, unresolved, and dialectical relation between what is pictured and what is written opens up the question of how text is used to structure and support the image. Harb’s exhibition takes this question to the level of the unconscious. Language here becomes a manifestation of an accessible—but not necessarily understandable—part of the unconscious, and the image is whatever seems to fool us. In this exhibition, we find ourselves taken inside the dark matter of the cloud, of the street, of geological formations, and we unquestioningly follow.

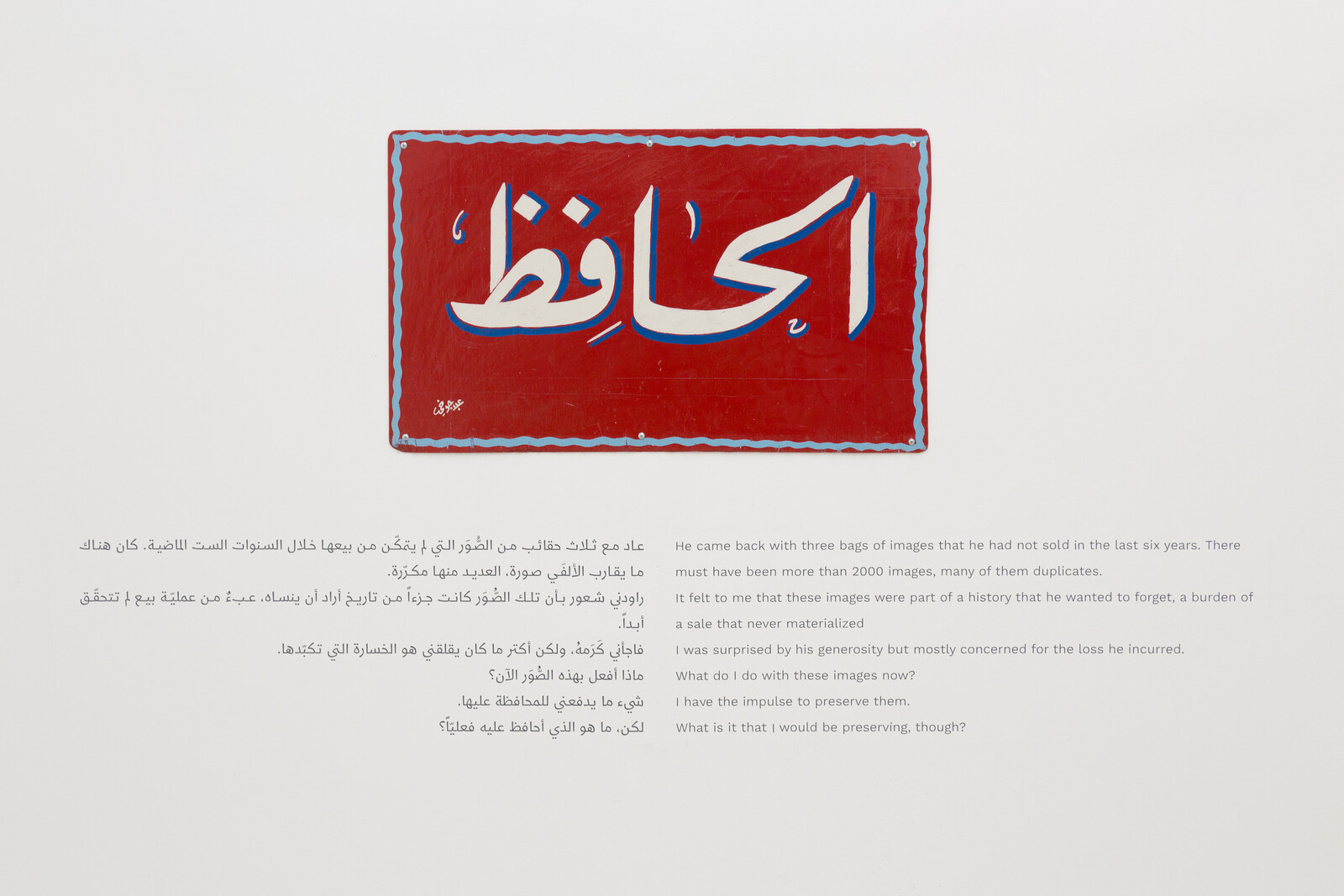

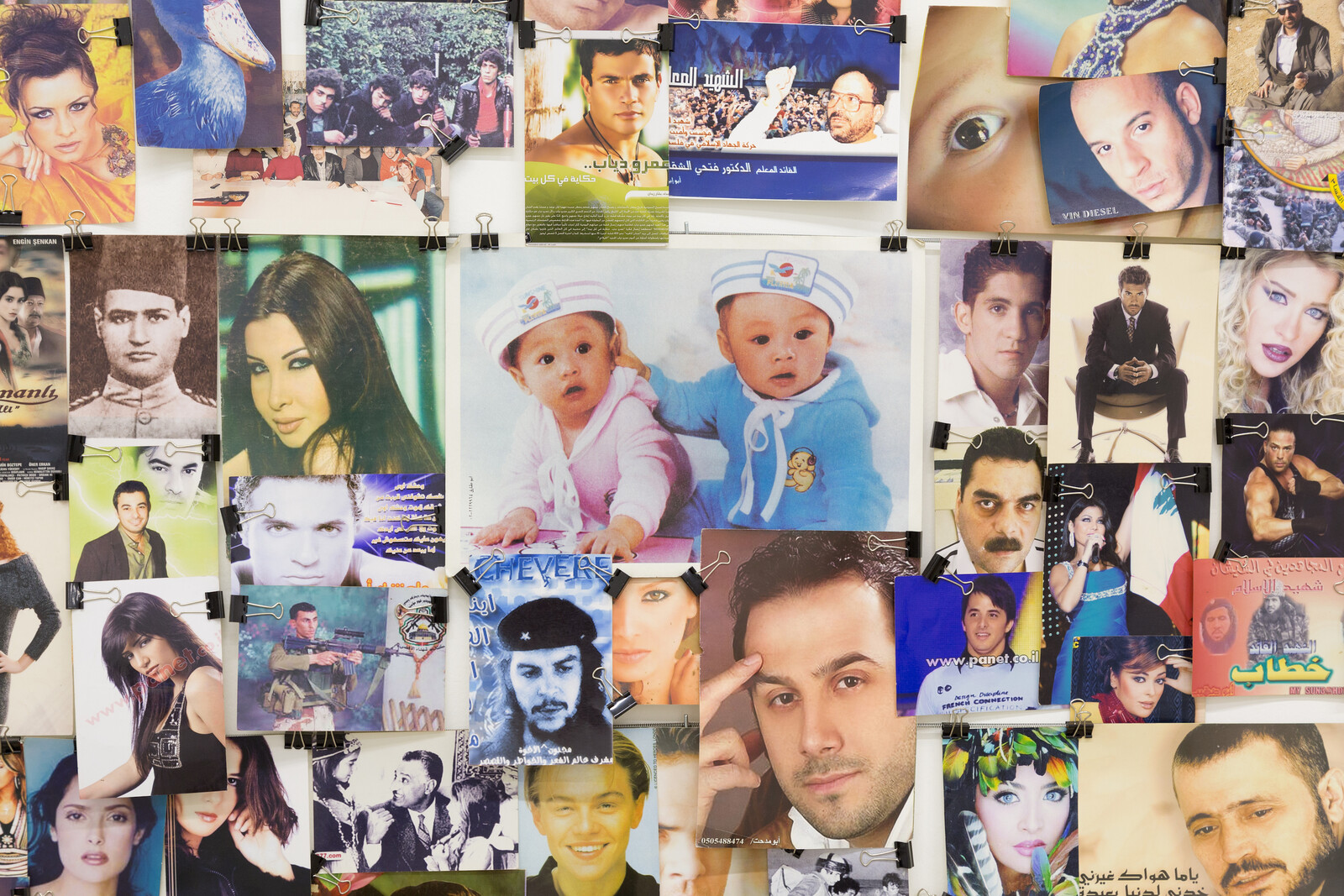

The wall text in the gallery’s main room is given as much space as two of the three works displayed in it: The Keeper (2010–14), an installation comprising a vast archive of photographs which the Ramallah-based artist sourced from a street vendor named Mustafa, and All The Names (2011/21), an installation of 207 steel street signs named after individuals with links to the city. The posters, street names, and wall text are overlooked by a third work: The Elephant and the Dove (2021), comprising two white, inflatable versions of the eponymous animals suspended one atop the other from the ceiling.

The artist’s work and world provoke a desire for the edge, for the abyss; not only in the manner of an adolescent thrill, but in questioning a liberal definition of freedom based on rights and centered on the individual. In her newest video The Jump (2021), which like her 2018 video The White Elephant is displayed in its own darkened room adjacent to the main exhibition space, Harb confronts us with a suicide, a freefall into the void. The work begins with a geological definition of depression: it is set in the “lowest point on earth,” the Jordan Valley. A computer-generated voice asks “if we jump from here, how high can we jump?” and wonders whether “it will be a happy accident or a detrimental crash.”

I watched the film in Beirut twice, first at the end of June and again at the beginning of September. As the economic collapse and political crisis induced by warlords and oligarchs worsened by the day, the accelerated crash was palpable between those two months. Truly, a freefall into the unknown. By September, shots of the Jordan Valley accompanied by a computer-generated voice resonated even more with the country’s downward spiral into a future that no one can predict. One of the protagonists/interviewees reflects on the young man’s suicide: “death is not easy even for someone who wants to die, so jumping itself is a fun experience,” she says. The question of seeing emerges again when this interviewee reveals that she is blind. The second protagonist/interviewee, who also has a sight impairment, talks about her trauma-healing practice, the feeling of belonging, and the alienation felt by a society under occupation.

“Ghost at the Feast” deals directly with this alienation: the fragmentation of the territory and the shrinking of one’s world into a bubble referred to as “Ramallah Syndrome.” The works in the exhibition become a call to take back the city. “It took me ten years to realize that the numbness of Ramallah is also part of the bigger picture of the occupation in Palestine,” the artist has said. “I am sad that my city is not so heroic, it is dozy and confusing. I realize now that Ramallah also needs to be reclaimed, to reject Ramallah is to accept that the Israelis have succeeded.”1

If bubbles are imposed places to which we retire after defeat in a neoliberal and colonial world, “Ghost at the Feast” teaches us that the struggle is neither resolved with a happy ending nor is it repressed and forgotten. Instead it comes back like a revenant, taking various latent or unexpected forms, including bursts into the street. The artist’s practice slowly and meticulously turns the colonizer’s narrative upside-down. Defeat is only a temporary state between uprisings and intifadas. It is what carries the future outburst, until the struggle reappears in a more palpable collective form. It always holds the promise of a future revolution. In the post-heroic world we grew up in, Harb’s exhibition walls—text, posters, street names—hold the history, the latency, and the future of the struggles’ transformation.

What we see, what we don’t see, what we hear, and what we read, is what we seem to know. But Harb confronts us with what is difficult to understand even if we know and can potentially explain it. The ventriloquized images (street and cloud) make for an intense exhibition experience, rendering both image and text at once ghostly and materially present. Take for example All the Names, in which the names of Ramallah streets resonate in Beirut. Harb’s world and work does something unexpected to language. It freezes it, melts it, unexpectedly confronts us with its dark sides, hollows it, and fills it with unexpected new meanings. It powerfully reminds us that the streets of Ramallah—its names, its posters of pop stars and ex-political prisoners—are in Beirut and that a piece of Beirut is in Ramallah.

“Syndrome” cities—in which one might assume that the neoliberal machine has annihilated any impetus for struggle—always surprise you. You don’t see any movement, then it unexpectedly explodes. Perhaps Harb’s work is about this revolutionary latency that takes a new form each time, and which, most strikingly, hollows the image to hear a new text.

Shuruq Harb, “A Ghost at the Feast”: https://darjacir.com/Shuruq-Harb.