When the HBO adaptation of the video game The Last of Us came out at the start of 2023, it already felt nostalgic for an earlier cultural moment of imagined future apocalypses. The game premiered a decade earlier among a “cohort” that included the TV series The Walking Dead (in its third season), the game Resident Evil (in its sixth), the Hollywood blockbuster World War Z, and Cao Fei’s morbidly humorous Haze and Fog, a zombie film that offered incisive observations of middle-class ennui and environmental ruin, inspired by Cao’s own fascination with eschatological imaginations in the broader culture. I remember being captivated by the zealousness of “world-building” efforts dedicated to sensationalizing its end.

In The Last of Us we follow the journey of Joel, a middle-aged smuggler who lost his daughter at the start of a global fungal pandemic, and Ellie, a ferocious queer teenager who has never experienced the world before its collapse, across America on a mission to facilitate the creation of a cure/vaccine. Many beloved zombie games at the time featured stereotypical characters or cliched trash-talk (which can become its own campy genre), but The Last of Us built indelible characters enlivened by high-quality acting. Joel’s and Ellie’s worlds collide at first, yet their bond deepens through surviving unfathomable ordeals and loss. The video game also felt fresh for its devotion to beauty, rather than mere visual sensation. The cinematic transitions—as subtle as the lyrical divisions of chapters into seasons—breathed a different rhythm into gameplay.

One of the most remarkable ways through which the gameplay immerses the player in the characters’ evolving dynamic is role-switching. The game presents a first-person perspective, and the player assumes the persona of Joel, thus bearing the lion’s share of problem-solving and combat. This continues until (spoiler alert!) he is wounded and loses consciousness towards the end of the game. The very next scene opens to a wintry forest in which the player suddenly embodies Ellie, hunting bunnies with a bow for sustenance. That shift in embodiment feels both exhilarating and scary: the weapons, resources, and skills accumulated as Joel are lost, yet the player gains a sense of agency and deep emotional reward from not only surviving a hostile world (as Ellie!) but also nursing Joel back to health. It also felt liberating as the player must know, by this point in the gameplay, that this headstrong, frequently cussing teenager has it in her to “endure and survive” (as the title of the fifth episode in the TV series puts it). The TV adaptation follows this plot faithfully to much less affective impact. This is the case especially when it comes to channeling the visceral rage and bravado of a teenage girl—things so rarely portrayed in gaming, and which many of us forgot to nurture in our adult lives.

Unsettlingly, the video game foresaw a global pandemic closely mirroring our recent experience, with its zombies the victims of a new strain of cordyceps militaris: the notorious “zombie parasite” that infects living insects and effectively transforms them into puppets. Ironically, cordyceps have been highly prized ingredients in traditional Chinese medicine for millennia; the game also curiously anticipates Anna Tsing’s The Mushroom at the End of the World (2015), as well as the general fascination with fungi as one of the most powerful and destructive collaborators in the ecosystem. The TV adaptation accentuates this grounding in realism through new prologues in which scientists explain the growth of fungal pandemics with reference to global warming and the interconnected international supply chain. Most significantly, the mode of infection was altered from the game’s contact with spores to direct consumption of, or stepping on, mycorrhizal extensions, which denote fungal roots in symbiotic relationship with other plant roots: a ubiquitous feature of soil.

The lush natural beauty of The Last of Us’s post-apocalyptic world, as well as the famous “giraffe scene” (in which Ellie—brutalized by growing up in militaristic Quarantine Zones—comes into contact for the first time with gentle wild animals), anticipate the media obsession at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic with rewilding narratives of the (much-fictionalized) “dolphins returning to the Venice canals” variety. At the same time, the world of The Last of Us is very real and frequently recognizable. Popular zombie apocalypse franchises like Resident Evil tend to place viral breakouts in places that are distant and exotic to US viewers: a small Spanish village, Hong Kong, western Africa, or straight-up fictional cities. The Last of Us, as the “US” in the title alludes to, is set in the home base and captures all that is beautiful, grotesque, even nostalgic in the landscape. When Joel and his brother ride through the Tetons in search of Ellie, one can always pause to admire the iconic snow-capped mountain ranges; the crumbled skyscrapers of Boston reveal intricate ruins fit for exploration, horror, and stealth play; the evangelist cannibalistic group and the abandoned mall, which miraculously facilitates young love as it generally would in pre-apocalypse times; the college dorms with familiar details and paraphernalia of campus life suspended in time, shrouded in spores and hazy light. The experience of fumbling through this eerily enchanting world as Joel induced pangs of my own first encounter, as a college student, with the United States.

Both the game and the TV adaptation ponder what love looks like in calamitous times. In the latter, Bill, a minor character and grumpy doomsday survivalist in the game, is granted an entire episode dedicated to his relationship with partner Frank. Ellie’s entanglement with her first love Riley is the subject in the game of an expansion chapter, coming after the player has cleared the main game, thus challenging and deepening the player’s understanding of the character. A storytelling feature that touched me in this expansion was how much the dialogue could digress at the player’s discretion. As Ellie and Riley wander through an abandoned mall, marveling and speculating at this archaic teen pastime, Riley gifts a pun book to Ellie. The game then gives players repeated choices to “joke” or “quit,” and I remember playing through the entire pun book, giggling with the characters. The silliness in this interaction captures the process of real bonds forming, and while this depiction of queer love was widely applauded for breaking new ground in gaming, it felt even more refreshing that it was done with such depth and nuance. I’ll refrain from describing the controversial ending and its take on the bond between Joel and Ellie, which clearly echoes the game creators’ notion that “love is not always good.” But however one defines the moral and consequential meaning of it, I am reminded of Etel Adnan’s observation that “love in all its forms is the most important matter that we will ever face, but also the most dangerous, the most unpredictable, the most maddening. But it is also the only salvation I know of.”1

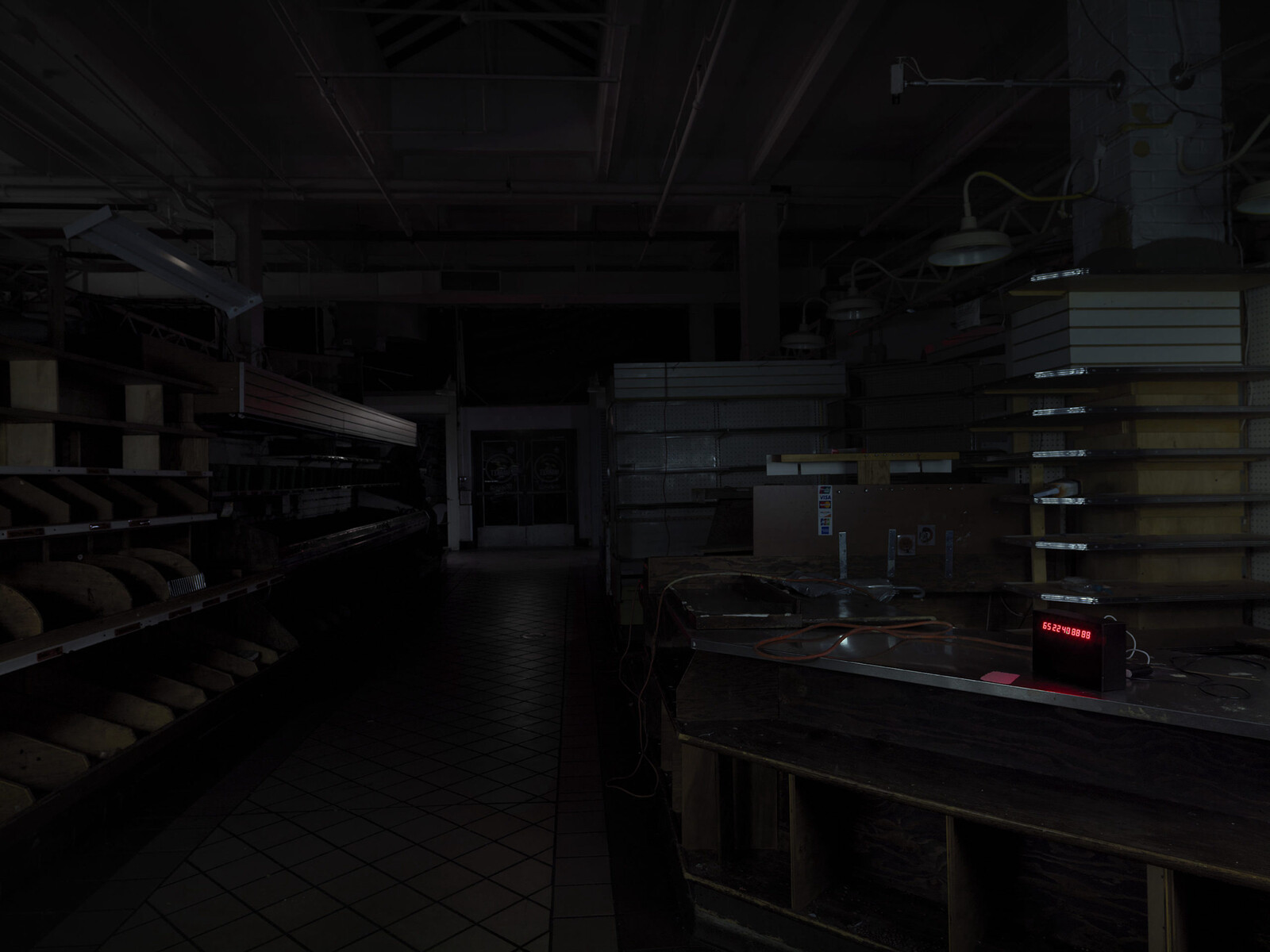

In featuring places and communities that register as familiar, the game simultaneously unfolds like a love letter to the American landscape while rendering America a post-apocalyptic Other. In this enchanting yet grotesque realism, another artwork that took place a few months before the Covid-19 pandemic came to mind. Titled 00 00 00 00 00 [Essex Street Retail Market] (2019), the installation by Andrea Nacciarriti took over the titular market on New York’s Lower East Side during the final phase of its closure, when only skeletal structures and signage remained of the empty shops and stalls. The artist painstakingly light-proofed the space, so that the eye had to adjust to the darkness before registering a ghostly, grayscale version of the market’s former self. Countdown monitors blinked red digits towards an unknown and unnerving end. A glowing, pristinely empty white cube, which hosted the market’s staple Cuchifritos Gallery + Project Space, stood in contrast to the gloom that befell the rest of the market—in part a humorous remark on modern art institutions’ architectural prototype. The work evoked the withdrawal of communities and memories that is innate to urban transformation, but it also whispered to a larger temporal frame, in which entropy is the only constant. It makes one wonder whether a new kind of survivalist romanticism might be created, and how it might look and feel.

Etel Adnan, The Cost for Love We are Not Willing to Pay (Berlin: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2011), 10.