At a moment when all kinds of anxieties can be tweaked by a tweeting president, Mel Bochner—a highly respected first-generation Conceptualist—has found his voice. Or perhaps I should say, these uneasy times have caught up with Bochner’s word-based art of language and ideas.

Other founding Conceptualists of the late 1960s— Robert Barry, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, Lawrence Weiner—formulated their immaterial ideas and the stenciled or neon words to articulate them early, and stuck with them, developing and refining them. In those days, Bochner’s dematerialized works questioned the measurement of space. When his early “Theory of Sculpture” series (1968-73)—made with numbers, lines, circles, white stones, and walnuts arrayed on the floor—was re-shown at Peter Freeman in 2013, Roberta Smith in the New York Times called the pieces “elegant thought puzzles.”1

But shortly after the turn of our century, Bochner went backwards to move forward. He embraced the old material-based act of painting on canvas. He began making enigmatic, hotly expressionistic, and sometimes illegible words with brushy, runny, dripping oil paint. At the time, some of us were puzzled by this apparently retrograde move by a highly theoretical artist who had studied philosophy. Was he still making Conceptual art? Or was he turning to materialistic objects with the intent of sociological critique, as had several artists of more recent generations, including William Powhida?

Bochner painted colorful bands of single words along with their synonyms—negative words, accusatory words, exasperated words, vernacular words, colloquial words, crude words—words as hot and expressionistic as his high-key color, his dripping paint, and his virtuoso brushwork. He painted a huge canvas titled Blah, Blah, Blah (2011), which repeated that meaningless word. Yellow and orange versions of it (both 2016) are on view in the show. In 2014, Ken Johnson, reviewing Bochner’s exhibition at the Jewish Museum in the New York Times, asked of the paintings: “What are they so worked up about? It’s hard to say.”2

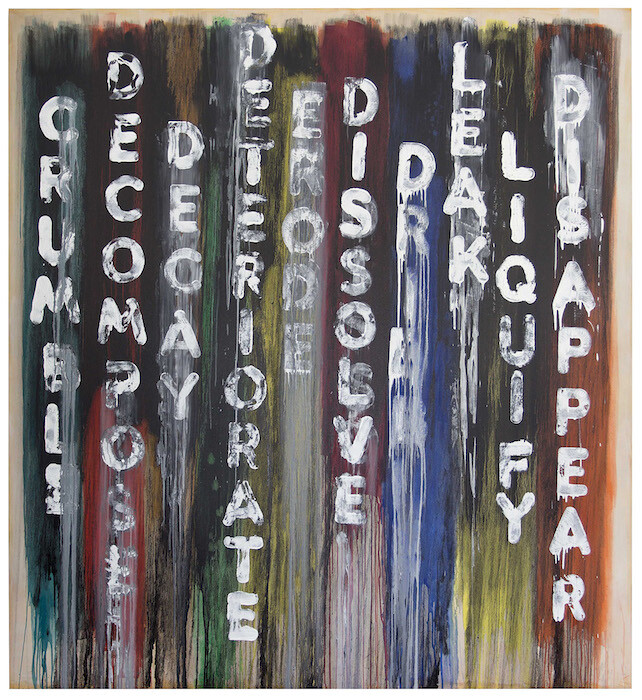

Not any more. His current exhibition of work from the past two years, titled “Voices,” opens with a modest two-part canvas, half-black, half-orange, titled A Fart…. (2016) On the black side, lettered in caps, it reads: A FART/A FUCK/A RAT’S ASS. One can’t help thinking of Jean-Michel Basquiat or Cy Twombly. It seems a message is trying to get through. Crumble (2016) is a study in entropy: its ten vertical bands read from left to right: “decompose,” “decay,” “deteriorate,” “erode,” and finally, “disappear.” Eradicate (2016) repeats itself until the word becomes erased to drippy illegibility at the bottom. $#!+$#!+$#!+ (2016) signifies the current ethos: money, statistics, and power. On other works, the color is sublime and subtle: the fading words of Block Head (2016) tumble through white, ocher, olive, and gray; the words on White Noise (2016) are in bleached bands of whited-out pink, blue, and sand.

The colloquial, vernacular, slangy nature of Bochner’s repetitive words has become more insistent and also more debased, insulting, frantic. He uses language as a verbal weapon. And he uses the act of painting as an outdated, wry, second-hand—and mostly oppositional—imitation of its former self. Bochner’s ideas have always dealt with misunderstandings and the fallibility of measurement systems—of which language is one: it can measure one’s thoughts. “Language is not transparent,” stated Bochner’s dripping wall-work back in 1970. Bochner referred to that piece in his contribution to a panel discussion at the New Museum in 2010, and in his closing words that day: “All abuses of power begin with the abuse of language. The drips at the bottom are meant to represent the never-to-be-completed work of this critique.”

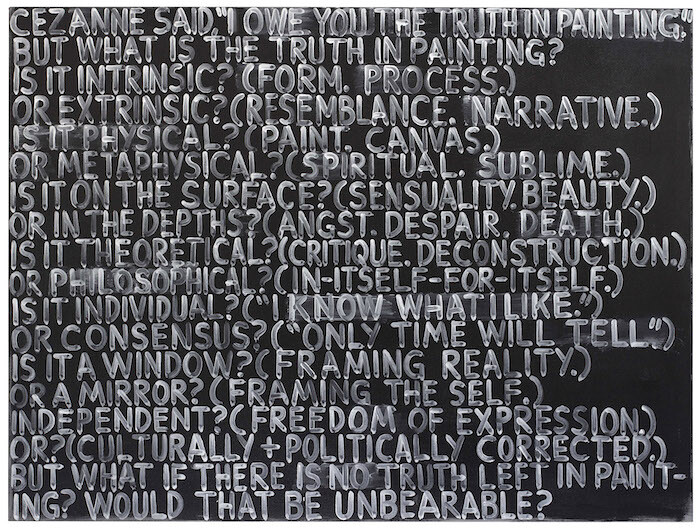

In the midst of the current exhibition there is one single painting, Cezanne Said (2016), which tries to communicate a transparent message about art’s current dilemma. “Cezanne said, ‘I owe you the truth in painting.’” Read the text and despair at its final words: “But what if there is no truth left in painting? Would that be unbearable?” In the non-verbal age of Twitter, Trump, simplistic “likes,” ambiguous emojis, and actual news as unbelievable as news which is deliberately faked, any belief in language as communication is already damned. And in this toxic atmosphere, Bochner’s eloquent word paintings—dealing with the de-meaning (and demeaning) of language—seem almost Shakespearian. They may just be the most vicariously political paintings of our troubled time.

Roberta Smith, “Calculus with Chalk, Stones and Walnuts: ‘Mel Bochner: Proposition and Process’ at Peter Freeman,” The New York Times, May 23, 2013: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/24/arts/design/mel-bochner-proposition-and-process-at-peter-freeman.html.

Ken Johnson, “Secret Power of Synonyms: Mel Bochner Turns Up the Volume in ‘Strong Language,’” The New York Times, May 1, 2014: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/02/arts/design/mel-bochner-turns-up-the-volume-in-strong-language.html?_r=0.