During his two terms as mayor, Eduardo Paes rewired Rio de Janeiro into a leading “smart city”—a raise of the six-million-resident city’s foundation that he was able to parcel out into a few crisp segments of a neat, satisfied TED talk. He dispensed the recipe for urban achievement: find and open green spaces; install and expand high-capacity public transportation; urbanize favelas, or, “favelas are not always a problem”; and, most important, institute a centralized operations system, or “no files, no paperwork, no distance, 24/7 working” (“a city of the future has to use technology to be present”). 1 Follow these rules and your city can too attract tourist dollars and host the Olympic Games.

It is the latter point, molding a brain for your smart city, that is the most striking, most vulnerable to manipulation, and was met with the most roaring applause from the Long Beach, California audience. The IBM-engineered Operations Center of Rio monitors municipal services around the clock, offering live transmissions from any city bus and trash pickup truck, relieving traffic jams, illustrating weather reports in granular detail. The surveillance state, now a source of celebration and case studies, is a twenty-first-century course correction for a city—region, continent—suffocated for generations by varying degrees of systematic corruption, inflation, and dictatorship.

A cultural parallel of this deliberate, responsive citywide strategy for integration has taken form in Los Angeles, the largest Latin city outside of Latin America: “Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA.” The Getty Museum’s third iteration of its curriculum stretching all across and past the city landscape, includes an immense, rooted and rigorous, richly generous program as narrative of the ethnic communities that continue to fill it, yet remain categorically underrepresented. Using a diversity of platforms as a means of resistance to any categorization and compartmentalization of Spanish-speaking populations and aesthetic traditions, 70 venues including universities, alternative spaces, private foundations, commercial galleries, libraries, the Hollywood Bowl, squares of grass, and museums (dedicated to African-American, Chinese, Japanese cultures; design and crafts; and, some to modern and contemporary art) stagger exhibitions over an extended season.

Many focus on art of the past half-century, but some, like the Getty’s own “Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas” reveal rare objects and precious materials dating back to 1,000 BCE; the Laguna Art Museum’s “California Mexicana: Missions to Murals, 1820–1930,” meanwhile, details the public artworks and architecture from the era when California was part of the United States of Mexico; and “Sacred Art in the Age of Contact: Chumash and Latin American Traditions,” traces the area’s early Mission period in the mid-eighteenth century, spread over multiple institutions in Santa Barbara—a hundred miles from Downtown LA. Five years in the making, “Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA” may flatten the scope of a global capital’s cultural offerings for nearly half a year, but the city is long overdue a lesson on its own history.

One of the tent poles of “Pacific Standard Time” is the Hammer Museum’s “Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985,” part of a wave of substantial surveys held together by the singular theme of female artists. This represents a fashionable, nevertheless welcome, canonical adjustment in Los Angeles, home of the historical living monument the Women’s Building (1973–91) and currently the host of multiple monographic exhibitions by women including Anna Maria Maiolino (MOCA and Hauser & Wirth) and Laura Aguilar (Vincent Price Art Museum). The show is sincere in its inclusivity, as well as its subjectivity: participants are arranged by country in the comprehensive catalog, yet grouped together by themes such as regime control over language and communications (“The Power of Words”), the self-portrait, and the performative body in the museum.

Interestingly, the groupings make no categorical distinction between Latina and Chicana artists—those from Latin American countries and US citizens with Mexican ancestry—liberating Chicana art from the expectation that it should remain faithful to activist stances on inequality, immigration, and feminism. A topic as broad as “the body” takes on laser precision and multiple objectives, moving from the enveloping, primitive affection of Cuban Ana Mendieta’s Corazón de roca con sangre (1975) to Peruvian Teresa Burga, of the influential Arte Nuevo group, whose Autorretrato. Estructura. Informe, 9.6.1972 (1972) is a self-portrait sketched in metadata: electrocardiogram charts, head and profile shots, and official documents. Works by Brazilians Lygia Pape and Celeida Tostes (O ovo, 1967 and Passagem, 1979, respectively), or Argentine Marta Minujin’s La Menesunda (1965)—which included a papier-mâché woman large enough to accommodate passersby in its entrails— and Statue of Liberty lying down (1979)—a proposal for a full-scale replica in recline and within eyesight of the original—creating rudimentary wombs from which to exit at the artist’s or visitor’s discretion.2 By doing so they obliquely undermine patriarchal and authoritarian restraint, presumably to re-emerge under more favorable historical conditions.

Photography has been positioned as a distinctly political act in several other presentations. The Getty’s “Photography in Argentina: 1850–2010” writes artistic agenda as nation-building. The show argues that the medium is one of the sharpest tools in sculpting a modern, sophisticated national identity for Argentina. With its roaring economy and substantial middle class, and a population inclusive of both liberal minorities and a sizable number of European immigrants (to the exclusion of indigenous populations and postcolonial instability) at least until its 2001 financial crash, the exhibition locates the state as both central within, and distinct from, its South American neighbors.

The exhibition begins with “Civilization and Barbarism,” a category which takes its name from the subtitle of Domingo Faustino Sarmiento’s heroic novel Facundo (1845) (the author became Argentina’s seventh president in 1868). Between the National Myths illustrated by the albumen silver prints of the noble, confident gaucho, chromogenic photos of malambo dancers, and glamorous grayscale headshots of a blonde Eva Perón are more conceptual images. These include Martín Weber’s late-nineties series “Ecos del interior”—quotidian portraits of citizens, quiet cafés, and libraries adorned with evenly fading movie posters and late afternoon sunlight in a romantic, poetic countryside—and Gustavo Di Mario’s portraits of queer dancers in his 2005 series “Carnaval.”

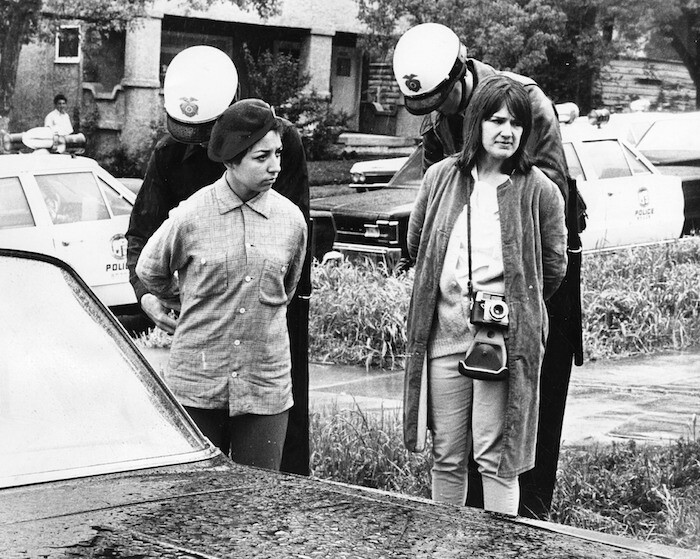

Compare this to “LA RAZA,” the Autry Museum of the American West’s cooled, full-disclosure archival exhibition of 25,000 photographs from the bilingual newspaper of the same name, published in Los Angeles from 1967 to 1977. An index of El Movimiento, the Chicano struggle for civil rights and solidarity, the exhibition’s inclusion of every photo contrasts sharply with the artful selectivity of Argentine photography as it is represented by the Getty. Further tracing political movement through the individual body, the show documents everything from the 1,000-mile-long Marcha de la Reconquista in 1971 to children carrying protest signs stating “a shotgun is not a search warrant” in response to the incidental assassination of Los Angeles Times reporter Ruben Salazar, clinical photographic evidence of police brutality, young students and nuns, and makeshift funeral processions. The body as shelter, as a fraction of community, as a means of resistance.

“Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA” does as much to reveal obstructed histories as it does to cement communities. Latin American commercial showrooms and artist-run spaces band together to share temporary spaces Ruberta and proyectosLA, while artists such as Argentine-born, Los Angeles-based David Lamelas receive synchronized exhibitions at the University Art Museum, CSU Long Beach, as well as commercial galleries Sprüth Magers and Maccarone. The citywide project also introduces artists outside of their gallery stables, such as f.marquespenteado, who shared a lavishly absurd tactile spread at Freedman Fitzpatrick; the psychedelic household objects of Mexican Pedro Friedeberg at M+B; and “Via Viva,” Alina Perkins’s affectionate, rebellious, unauthorized addition to PST with a group show of mail art from her native Argentina. Taking place in her Los Feliz studio, the exhibition echoed Graciela Gutierrez Marx’s postal acts and featured everyone from Fernanda Laguna, prominent in LACMA’s sprawling “A Universal History of Infamy,” to Victoria Colmegna before her PST exhibition at apartment gallery Park View, while “Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano LA” at MOCA and the ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archive historicize and formalize the cultures of marginalized populations in the city.

The first wave of PST exhibitions opened in early September, days after the 45th American president announced his intention to rescind DACA, a federal program protecting undocumented immigrants, often Mexicans, from deportation, and using the same self-reported government records of registration to tally who now needs to be deported. This is to say nothing of his curt dismissal of the devastation wreaked by Hurricane Maria on the US territory of Puerto Rico. The cruelty of a state using technological and capital gains to wield its own protectorate and directing its federal, centralized operations system to further divide Americans who are classified as innocent victims of mainland disasters (Texas, Florida) from citizens of the same nation who are not deemed American enough reminds us again that a determined campaign such as Pacific Standard Time is not a matter of course, but a matter of priority.

Eduardo Paes, “The four commandments of cities,” TED talk (February 2012), http://www.ted.com/talks/eduardo_paes_the_4_commandments_of_cities. Thanks to Tim Ivison.

As cited in the catalog by Connie Butler, “Fallen Monuments: The Feminist Continuum,” Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985 (Los Angeles: Hammer Museum and DelMonico Books, 2017), 43.