Even before it opened, “Theater of Operations: The Gulf Wars 1991–2011” had attracted critical attention. A string of scandals highlighted once again just how embedded museums like MoMA, and its affiliate PS1, are in the military and prison industrial complexes responsible for so much of the devastation on display in this exhibition. Phil Collins’s withdrawal of his work from the show late last year, in protest of some MoMA board members’ investments in private prisons and ICE detention centers, was followed by a request from Iraqi-American artist Michael Rakowitz that the curators “press the pause button” on his video in order to “discuss some recent events.”1 After PS1 ignored Rakowitz’s request, the artist paused the video himself, in January this year, and posted a statement explaining his position on the gallery wall beside it. The museum quickly removed the statement, despite the artist’s insistence that it “constitutes an essential part of [the] ongoing artwork.”2 Three dozen participants in the show have since signed a letter urging the museum to sever ties with controversial trustees. Meanwhile, at least four Arab artists, including Netherlands-based Afifa Aleiby, were denied visas to attend the opening. Others knew better than to apply.

The absence of these participants underscores how urgent it remains that western audiences are able to see works by artists from the Middle East. “Theater of Operations” features 36 Iraqi and Kuwaiti artists, working in their home countries and the diaspora, who represent a broad generational range from pioneers down to those who came of age during the US-led invasions. Engulfing the entire museum, the exhibition is simultaneously overwhelming in scale—it features over 300 works by more than 82 artists—and underwhelming in its uninspired reproduction of the mainstream narrative surrounding the Gulf Wars, the end date itself proposing the US withdrawal as a conclusion to the conflict, even as the violence continues to reverberate throughout the region.

“Theater of Operations” opens with some serious bling. Thomas Hirschhorn transforms the CNN logo into ostentatious jewelry. Hanging from a heavy gold chain in the entrance, Necklace CNN (2002) announces the exhibition’s preoccupation with the way the production and consumption of news has transformed since the start of the Gulf Wars. This much-theorized perspective is not so much developed in the exhibition as exhausted; Michel Auder’s Gulf War TV War (1991/2017), Alia Farid’s Theater of Operations (The Gulf War seen from Puerto Rico) (2017), and Dara Birnbaum’s Transmission Tower: Sentinel (1992)—to name only a few—incorporate recorded television coverage from the all-pervasive 24-hour news cycle. Screens invade the exhibition spaces, the din of the broadcasts a ubiquitous echo.

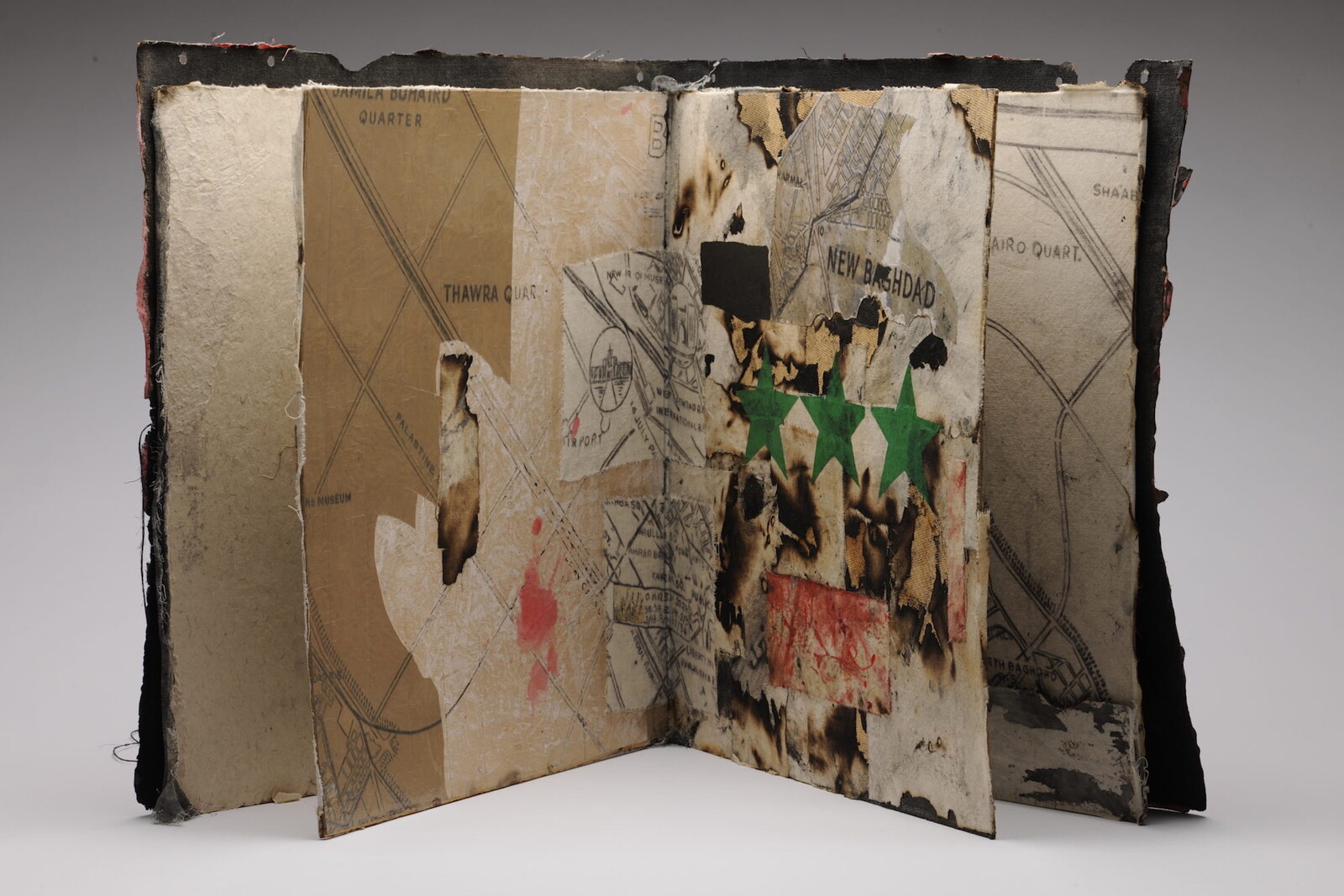

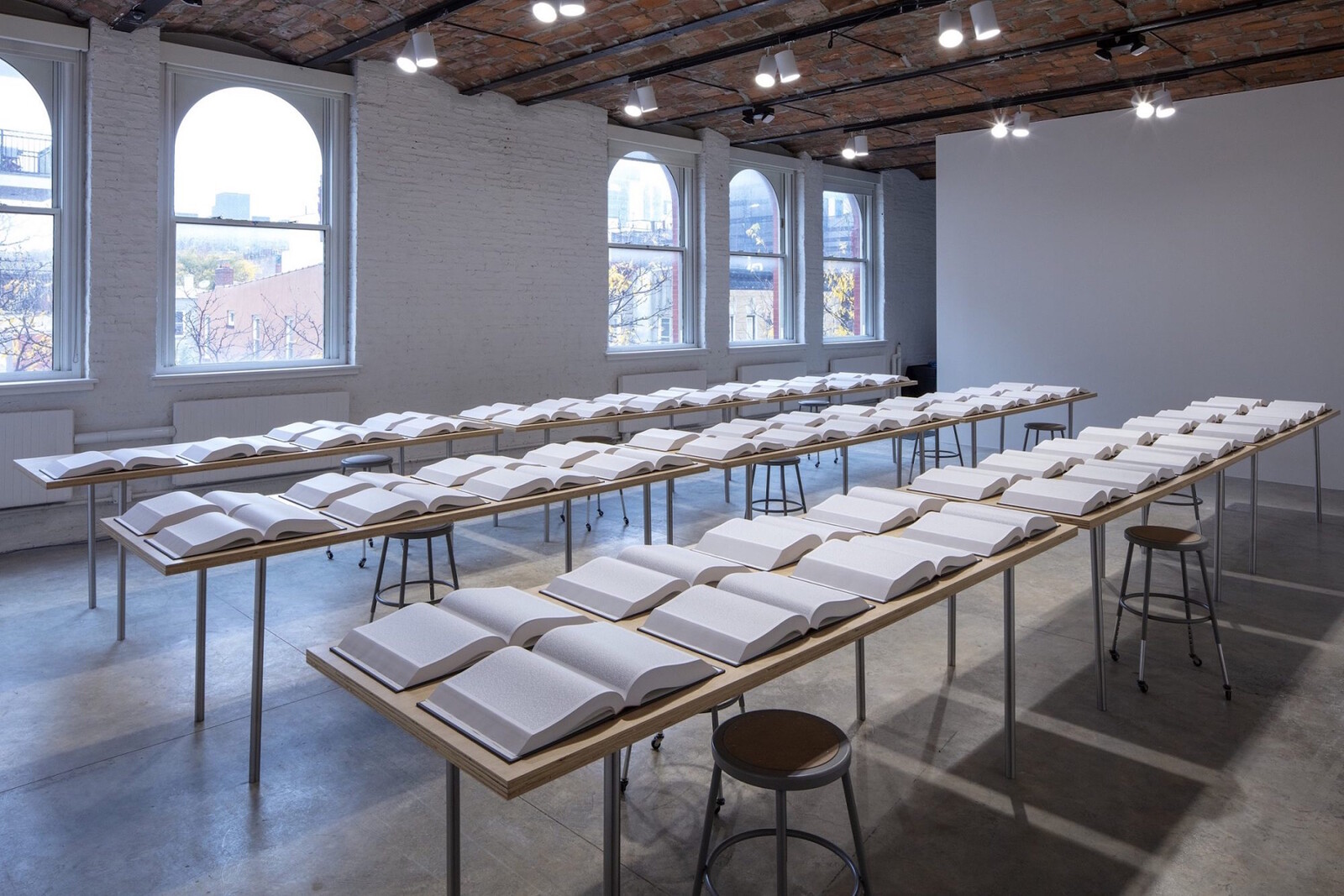

In Iraq, the experience of war has had material consequences for artistic production. “Theater of Operations” includes a large number of dafatir (notebooks), an art form pioneered by Dia al-Azzawi in the 1980s, that became popular among Iraqi artists during subsequent decades as art supplies grew scarce. Kareem Risan, Rafa Nasiri, Mohammed Al Shammarey, and Hanaa Malallah handcraft sketchbooks from available materials, such as wood, capturing the horrors of war with a quiet intimacy that stands in stark contrast to the loudness of some of the large-scale installation pieces by European and American artists. In Untitled (Iraq Book Project) (2008–10), Rachel Khedoori utilizes the book form to reflect on the unknowable vastness of the US involvement in Iraq. Starting in March 2003, the artist collected every online article that mentioned the words “Iraq,” “Iraqi,” or “Baghdad” and bound them in 70 large white volumes. Meticulously displayed on long benches, the invitation to browse through the tomes is overwhelming.

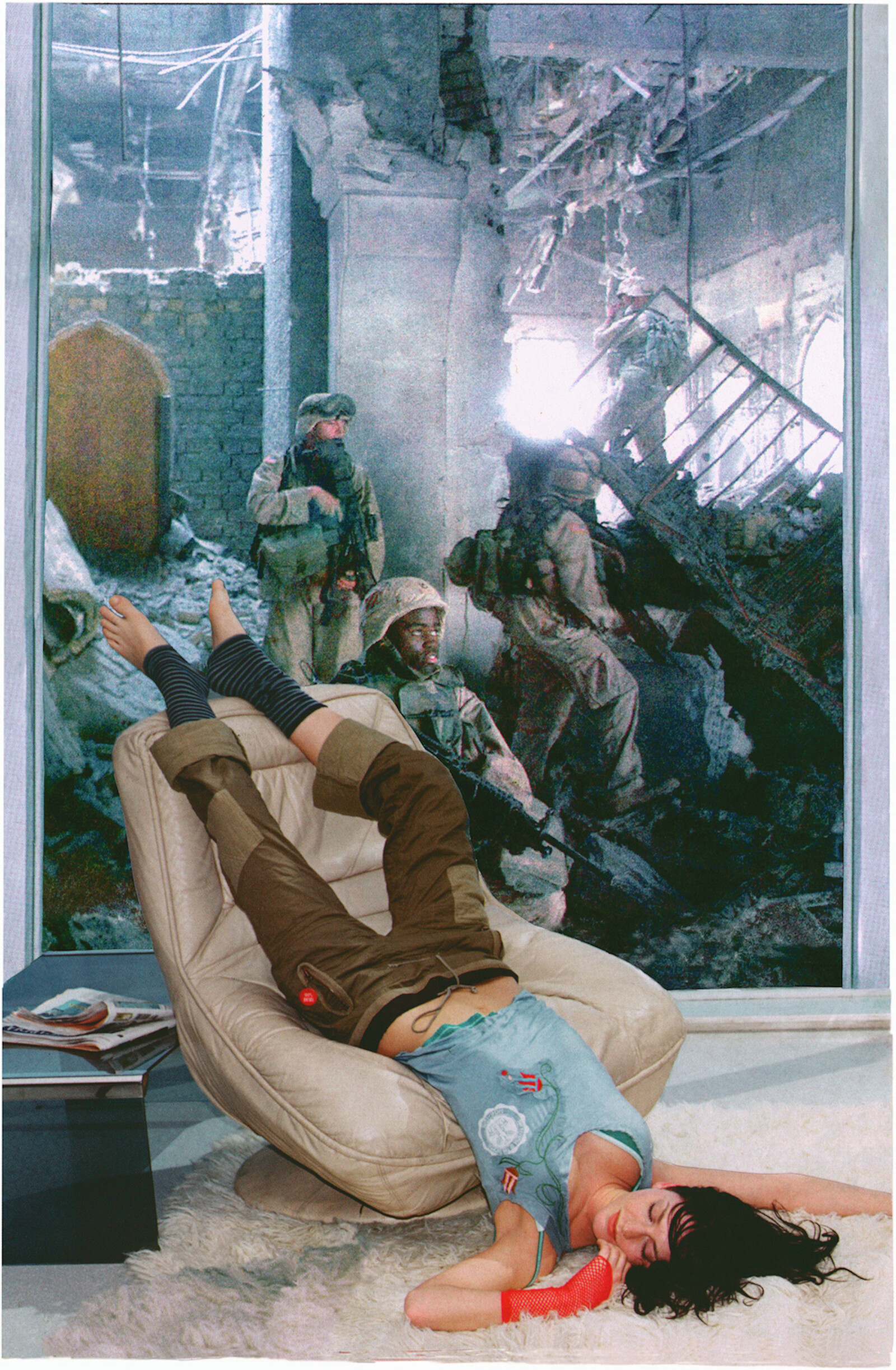

The conversation between artists who live and work under conditions of war and those who respond from a distance is never quite realized, even where connections are evident. In Saddam is Here (2010), Jamal Penjweny captures Iraqi citizens engaged in everyday activities while hiding their faces behind a black-and-white photograph of the dictator. The bleak humor of these photographs encapsulates life under an authoritarian regime, the specter of which is omnipresent and persistent. Similarly, Martha Rosler has revisited photomontage, her powerful tool of critique during the Vietnam war. In “House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, New Series” (2004), she once again inserts images of war and violence to disrupt the banal beauty and tranquility of domestic spaces and encourage audiences to connect the two conflicts. In one of the exhibition’s most jarring pieces, the video Evil.16 (Torture.Musik) (2011), Tony Cokes combines explicit, emotionless descriptions of torture with a blaring soundtrack of popular American music, a tool of torture in Abu Gharib prison.

“Theater of Operations” follows a chronological approach, moving from the 1991 war to the 2003 invasion and subsequent occupation. However, little separates individual rooms from each other or creates a sense of cohesion within them. Instead, artists appear and reappear in endless succession, at different points in the historical trajectory yet accompanied by unchanged wall texts. Perhaps the intention is to replicate the persistent and interminable cycles of violence committed in Iraq and the surrounding region. Yet ultimately, it is disappointing that this overdue exposure of Iraqi and Kuwaiti artists is framed by and restricted to war, contributing yet further to American audiences’ limited knowledge of the Middle East.

Zachary Small, “Michael Rakowitz wants to pause his video work at MoMA PS1 as a protest against museum’s ties to ‘toxic philanthropy’,” The Art Newspaper (December 2, 2019).

Hakim Bishara, “After being ignored by MoMA PS1, Michael Rakowitz paused his video in its Gulf Wars exhibition,” Hyperallergic (January 13, 2020).