Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève, Geneva

November 8, 2018–February 3, 2019

The press schedule for the opening days of the Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement (BIM) included a special visit to CERN’s “Antimatter Factory.” Our guide was a cheerful Chinese-American engineer who laughed at my astonishment when he explained that our knowledge of the universe—stars, planets, galaxies—amounts to its visible 4 percent. The remaining 96 percent is composed of “dark matter,” i.e. something we know nothing about. Given the dim political climate around the globe, the idea of an ontological fumbling in the dark with the help of a risible fraction of enlightenment felt spot-on.

As in deep space, darkness and dark energy also abound in this year’s well-researched BIM. Its thunderous title, “The Sound of Screens Imploding,” echoes the Big Bang, but also the collapse of a dying star: the Big Screen. “The long era of projection on screens is coming to an end,” curators Andrea Bellini and Andrea Lissoni state in their introductory text in the exhibition booklet, “and will give way to environments that reverberate with the radiant echo of their implosion.” It’s exciting to think of moving images as light and sonic waves expanding across space and cyberspace, past the constrains of beamers, reflective surfaces, or human vision. And yet, the counter-escalation of small portable screens seems to restrain human perception of reality within increasingly individual, myopic, and oppressive frames.

Compared to the previous iteration, BIM contracted, in terms of number of works exhibited as permanent installations at the Centre d’Art (eight), of films screened at Cinema Dynamo after the opening (nine), and of live performances during the vernissage (three). But it also expanded in terms of commissions and format. All 20 works were made for the occasion and many will travel to Officine Grandi Riparazioni, Turin, and the Swiss Institute, New York, in the coming months, while other screenings will take place in London, Verbier, Venice, Athens, Madrid, and Palermo.

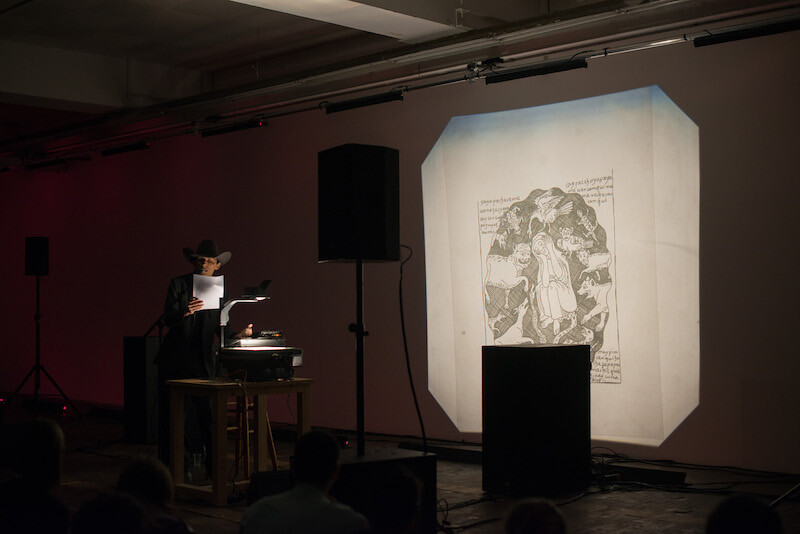

Sound, as the title points out, plays a key role in this edition. Visitors entering from Rue des Vieux-Grenadiers find themselves in Andreas Angelidakis’s Demos Bar (all works 2018), where layers of golden foil wrap walls and furniture, and lead up the stairs to Orcorara (tres estrellas todas yguales) [Orcorara (three identical stars)], an immersive environment by musician and artist Elysia Crampton. Twelve speakers play fragments of music and amplify oral tales about love, negativity, ancient gods, and black rainbows based on the writings of seventeenth-century Aymara chronicler Joan de Santa Cruz Pachacuti Yamqui Salcamaygua, from the region between Cusco and Lake Titicaca in Peru. A dance of shadows accompanies Crampton’s score (which runs in a loop of around 70 minutes), created by the changing colors and brightness of a set of neon lights. On the opening night, Crampton stood in the middle of the room and delivered a lecture-performance that got the audience lost in translations, as well as in a maze of references to multifaceted Inca iconographies.

Another entrance to the exhibition, located in the lobby of the Centre, is filled by the soundtrack of Kahlil Joseph’s video BLKNWS, edited in the fast pace of news channels. “Don’t you fuck with my energy” sings Princess Nokia, while footage of past and present black celebrities in the US is split between two LCD screens. During the opening, BLKNWS was screened in a special linear version ending with Chris Cunningham’s music video for Björk’s “All is Full of Love” (1997). Watching it now made me realize for the first time how white, polished, and candid were the erotic and robotic bodies of the “aliens” in the video.

On the second floor, Party by the CAPS, a multiple screen video installation by Meriem Bennani, is a showstopper with a political statement. With much irony, energy, and masterly digital post-production, the artist portrays life on CAPS (from capsule), an imaginary island in the middle of the Atlantic—with “one stadium, 86 clubs and 930,000 handmade phones,” as an animated crocodile describes it. There, illegal migrants are confined after being intercepted halfway to the US via teleportation. A “complete quantum mess” ensues: individuals get randomly remixed, so that “the idea of having a body is never taken for granted,” as one of the characters says. Shot in the artist’s native Morocco with the help of family and friends, the video is populated by green-clad men and women, singing and dancing to pounding music, eating all-green food under the guiding light of green crescents, in a crescendo of Arab futurism. Neïl Beloufa resorts to grotesque to tackle exclusion, cultural clichés, and forced isolation. His (too long, at 77 minutes) film Restored Communication, shot in Iran during a residency and largely based on improvisation, adopts the schemes of reality TV survivalist games and action B-movies, as well as the DIY aesthetics of school plays. When surveillance cameras switch off and food stops arriving, the characters confined in a townhouse turn to violence: a cruel king emerges, crowned with kitchen forks.

On the top floor, Tamara Henderson’s Womb Life includes a series of Jean Tinguely-esque kinetic machines acting as imaginary crew members of the artist’s film, whose gestation emerges from a constellation of sketches, notebooks, drawings, scraps of paper, and a diary of all the dreams she had during her (real) pregnancy. With Walled Unwalled, Lawrence Abu Hamdan continues his forensic investigations on how acoustic perception can turn into legal evidence, even when experienced through walls. Retro-projected on a blurry glass surface, the video stems from Abu Hamdan’s investigations into Saydnaya Prison in Syria. It embodies the prisoners’ difficulty in identifying, from afar, the sounds related to unthinkable physical abuses, without directly witnessing violence. It also reflects on how often they base their interpretations on the familiar though fictional soundtracks of films, radio, or TV.

Korakrit Arunanondchai and Alex Gvojic’s No history in a room filled with people with funny names 5 (2018) is literally a dark cave, covered from floor to ceiling with layers of stinky soil made of loam, shells, and latex paint, inhabited by stuffed animals and animistic sculptures, and pierced by moving images and the green rays of a laser harp. Arunanondchai also appropriates an online video on the Thai boys rescued from a flooded cave earlier this year, edited like an epic movie to match the notes of Whitney Houston’s “When you Believe” (1998). Seeing and believing hardly coincide, nowadays. By contrast, in This Action Lies James N. Kienitz Wilkins reduces his movie to a black-and-white image of a Styrofoam cup filled with hot coffee seen from different angles. The 32-minute voiceover monologue accompanying it is a stream of consciousness in which the author talks about truth, fiction, art, money-making, and his own ability to “fact-check myself” when “shit gets real.”

“The Shit Is Going To Go Down” was also the ominous mantra, projected on a roll-up screen, of Water Will (in Melody)/Preview by Ligia Lewis, staged at the Grütli Theater, on a black-box stage stripped bare, except for the play of voices, LED lights, and showers of falling water. Conceived as the epilogue of a trilogy including Sorrow Swag (2016, where the predominant color was blue) and minor matter (2017, focused on red), this black-infused performance involved four dancers, acting and moving in hyper-expressionist, exhausting, puppet-like mode, as if for a Weimar-era cabaret, or simply in tune with the gripping performativity of our age.

On the train home, across the border via a tunnel under the Alps, I closed my eyes and thought again of CERN’s underground accelerator and its capacity to highlight energy that seems so hard to see. Art—and sometimes biennials—share a similar power. I thought of my favorite film of this BIM, Parsi, by Eduardo Williams, a sequence of perpetually moving images that unfolds for 20 minutes, along with the moving words of Mariano Blatt’s poem “No es” [It isn’t], where each line starts with parece [it seems]. The camera moves and rotates relentlessly, by car, bike, roller skates, it runs around like the mobile devices perennially attached to us, and follows a group of black queer youth in Bissau, whose fragmented bodies, identities, drags, jokes, and voices flash in and out of the frame, until the camera reaches the river and plunges into water, where all images are dissolved. “What seems to be but isn’t”—to quote one of the lines of Blatt’s poem—is there, never mind the mainstream.