January 15–February 25, 2017

As 2017 opens there is a sense that all bets are off—that it is time to roll the dice and keep a hand open to all possibilities. Perhaps this is all the more so in the Netherlands—in many ways the closest of the EU countries to Britain and perhaps facing its own democractic crisis with a fractious election ahead in mid-March. In a sense this is both the mood and the motive behind a new joint venture by six Amsterdam art galleries and their opening project, titled “Where do we go from here?” As far as gallery experiments go, the basic premise of trading in the art commodity remains unaffected. Nevertheless, within these limits something quite bold is taking place. This joint venture tries out a new, collectivized form of trading, possibly marking a turn towards locality within the art market and the cultural climate more broadly.

The project takes the form of a synchronized exhibition, with works selected from the galleries’ represented artists and arranged by invited curator Alessandro Vincentelli (Curator of Exhibitions and Research, BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead). Hot on the heels of the evermore successful Amsterdam Art Weekend in November, “Where do we go from here?” goes beyond the model of coordinated openings by actively mixing up gallery programs. Artists known for their long relationships with one gallery pop up in another, while the circuit of galleries throughout Amsterdam’s historic Jordaan neighborhood makes for a pleasant two-hour-or-so walk.

The initiative’s curatorial statement foregrounds language and communicability, pointing to the multiple democratic crises on either side of the North Atlantic. From this proposal the exhibitions cluster works in arrangements that produce more of a sense of tonality than a message per se.

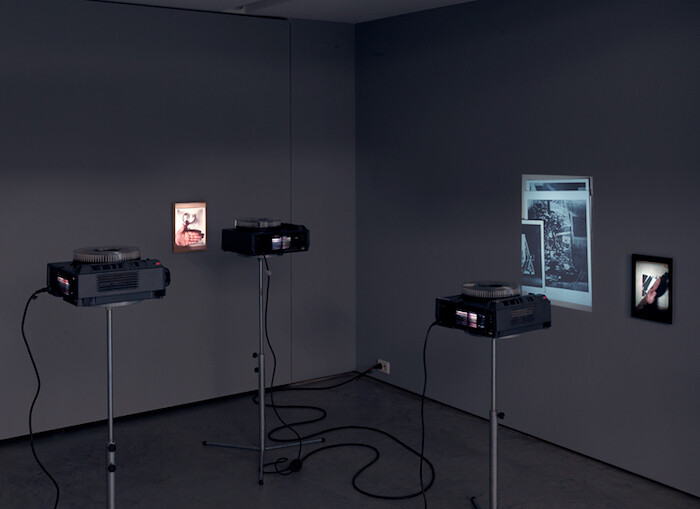

At Fons Welters, contributions by Falke Pisano, Otto Berchem, and Yael Bartana are sharp-edged and formal. Here, the gallery’s stark, unembellished rooms allow for a focus on the semiotics of art-making in its primary elements. Meanwhile at tegenboshvanvreden, extensive presentations by Slovenian artist Jasmina Cibic and Greek artist Antonis Pittas have a more elegiac sensibility. Across Cibic and Pittas’s multi-media installations, Enlightenment grammars of modern progress appear paradoxically faded and worn down by European history.

At Ellen de Bruijne a concise display investigates exchanges through capital, commodity, and symbolic forms, with contributions by Spanish artist Cristina Lucas, Argentinian artist Amalia Pica, and local duo Sander Breure and Witte van Hulzen. Paulien Oltheten’s video vignette of the politics of street-sweeping in a Greek village is a highlight here. Titled Sweeping (2016), its candid footage offers a humble view of the European debt crisis at the micro level.

South of the Rozengracht, the exhibition at Annet Gelink is more varied in tone with works by David Maljković, Hedwig Houben, and Dora García standing apart on their own strengths. Here, a series of small, typewritten pages by Sue Tompkins, Body Rocks (2015), casts a charming and captivating pall about itself, drawing viewers into the artist’s breathy litanies. Works by Dina Danish, Peggy Franck, Navid Nuur, and Maria Barnas at Martin von Zomeren carry a cheerful irreverence, while a sense of wit continues around the corner at Stigter Van Doesburg with celebrated locals Gabriel Lester and David Jablonowski. Here a series of canvasses by Anna Ostoya add a sense of visceral refusal to this humorous sensibility. With titles such as Morphisms (2016) and Uncle Me in Maidan Cloak (2016), the panels intersperse geometric patterning in oil paint with areas of papier maché newsprint and small cutouts of some of the “big man” politicians who dominate news headlines at present.

In a gesture of elemental connectivity, each gallery opened with a version of Chaim van Luit’s five sculptural “platonic forms,” while newly developed graphite text pieces by Antonis Pittas surface sporadically in three of the six spaces. Seemingly conversational text fragments, such as “in the new year,” are culled from news headlines and stenciled across walls and around corners in graphite. As a recurring presence they form a textual hinge to the show that has been installed painstakingly by hand.

Zooming out to consider these shows overall calls for a sense of the larger international art market, as well as the relative periphery at which Amsterdam is located within its cycles. The project’s motivation stems from a shared wish to navigate away from the art fair circuit, which the galleries experience as increasingly ill-fitted to their needs and to collectors’ tastes. Together the six galleries call themselves the “Nieuw Amsterdams Peil”—a riff on the mark of Amsterdam canals’ water-level relative to sea level, called the “Normaal Amsterdams Peil.” The implication is of some kind of a local standard amid fluctuating conditions.

Perhaps the initiative’s most remarkable feature is that the six galleries will pool and share profits made on sales of work—a proposition antithetical to the hyper-competitive atmosphere of the art fair. In terms of a certain local collectivity, the project also maps its walking path with an extensive list of local businesses who’ve chipped in everything from photography to wine and transport. The list also includes the pretty fantastic low-key lesbian pub Saarien, although it’s not clear what they brought to the table: the loan of a well-trained dog, a good adversary in a game of snooker?

At base it is this structural economic intervention that sets Nieuw Amsterdams Peil apart from other gallery initiatives—such as curated by_vienna, for example—perhaps charting a genuine alternative in the functionality of art trading. At best, this move could point to a collectivizing possibility in the broader retraction from market globality that—in Europe and the Anglosphere—has been so well co-opted by xenophobic and populist discourse. In practice this collectivity plays out in minor, yet charming ways—for example, the humorous experience of engaging gallerists to introduce work by artists that they don’t know, might not have chosen, might not even particularly like. And likewise the fresh view on work usually presented in one context suddenly appearing in another. It’s a decent, open, roll of the dice. And even at this early stage of the project, all involved seem to agree it’s an experiment that has been well worthwhile.