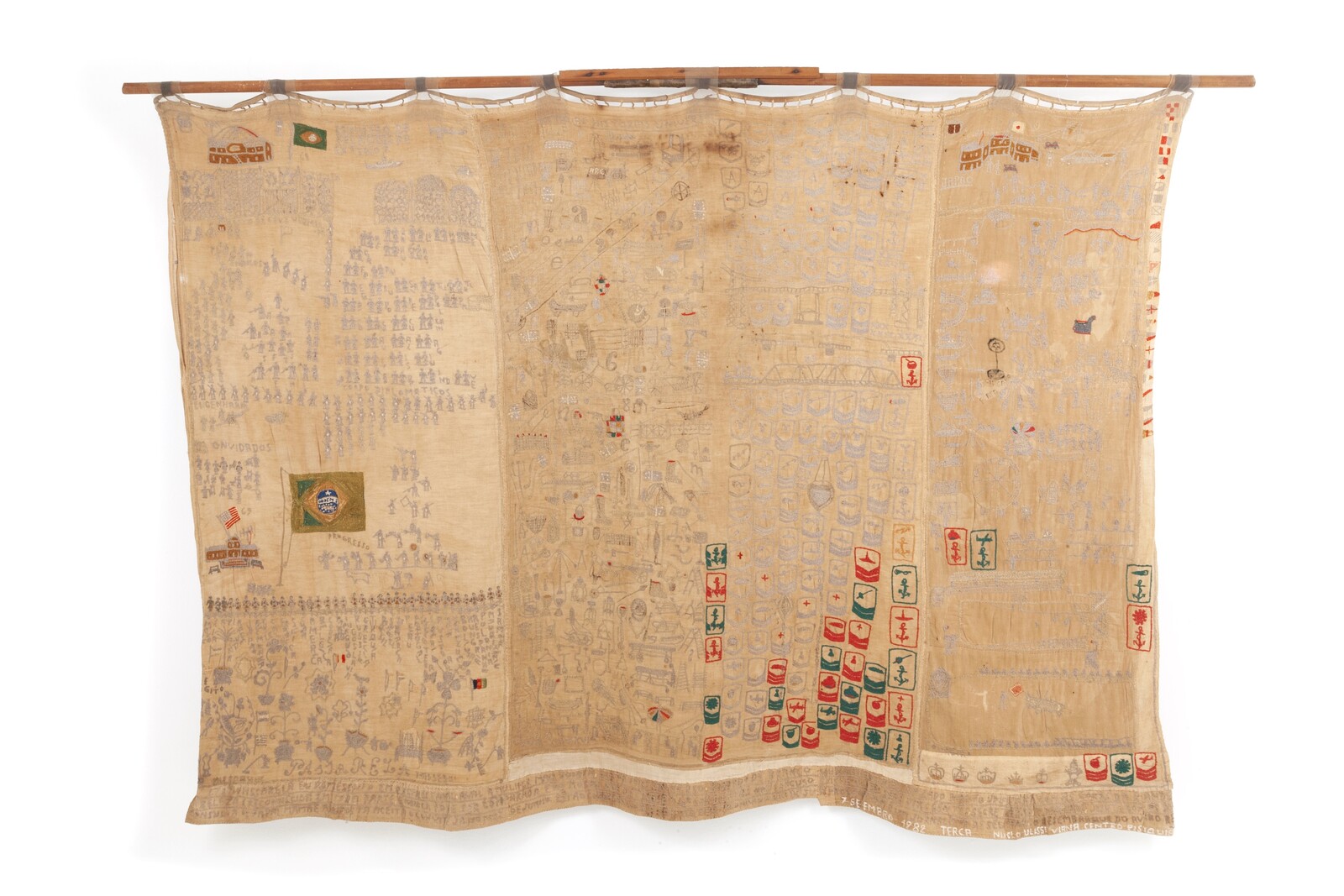

A number of extravagant garments, marked by generous color schemes and complex embroidery, open the first of three luminous rooms in “All Existing Materials on Earth,” curated by Tie Jojima, Aimé Iglesias Lukin, Ricardo Resende, and Javier Téllez. Its central piece, Manto da apresentação [Annunciation Garment], catches the eye with a multiplicity of details, inscribed with colored threads against a light-brown ground: signs and drawings of objects, names, numbers, abbreviations, and streets of Brazilian cities, utensils, boats and a model of a large sailing ship.

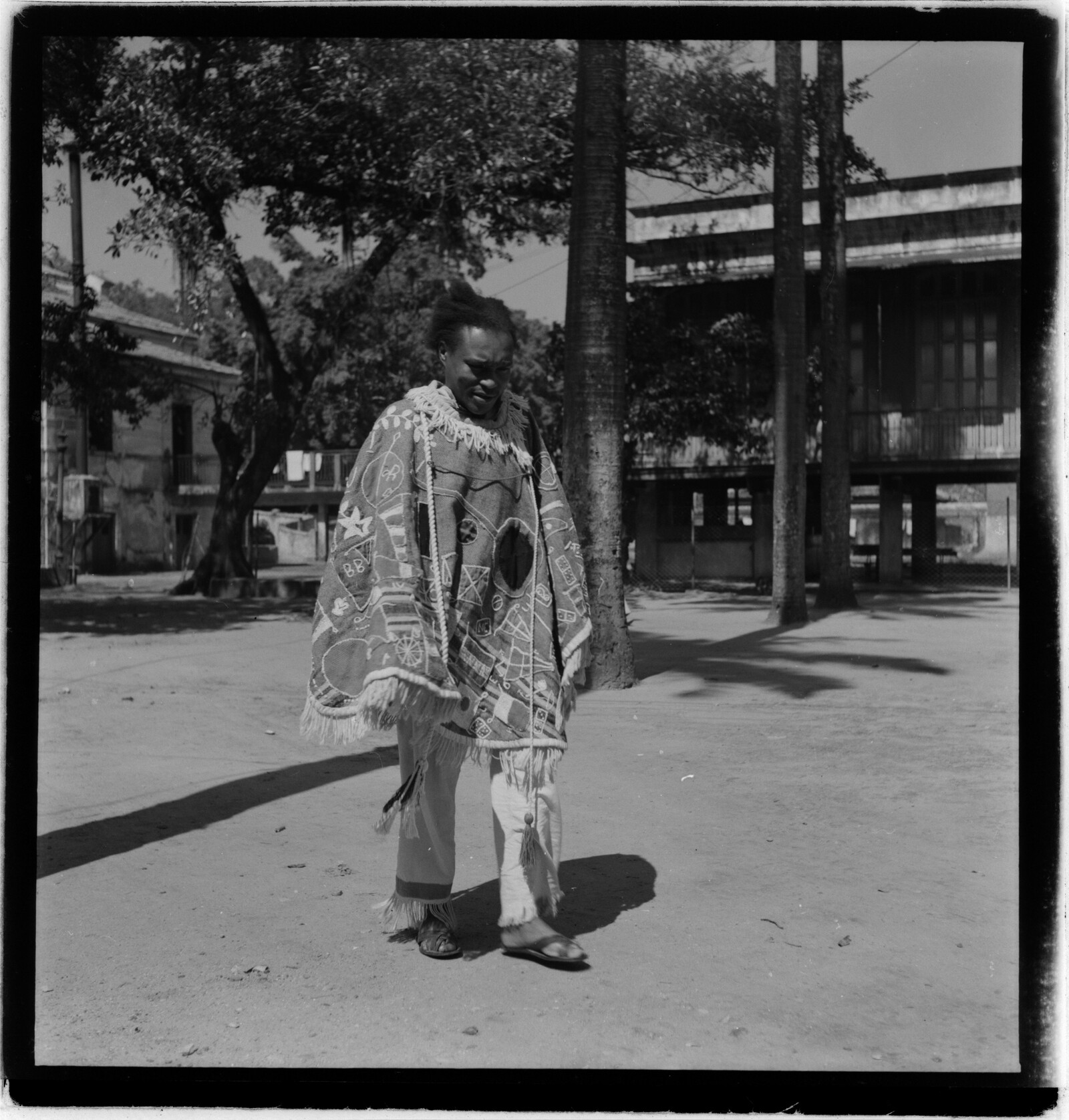

A photographic portrait of the artist wearing his magnum opus reveals not a fashion designer but a Brazilian psychiatric patient. The descendant of Black slaves, Arthur Bispo do Rosario (1909/11–1989) spent forty-one years of his life in mental health institutions while accomplishing his “mission.” On the side of the short exhibition text, another mugshot-like portrait of the artist is displayed on the patient card from Colônia Juliano Moreira, the hospital where Bispo was interned. He is described as “indigent,” a wandering Black beggar bearing no documents. The card repeats the police record from December 1938, when Bispo was arrested in Rio de Janeiro and diagnosed with “paranoid schizophrenia.” It was the month of Bispo’s revelation: he started to hear voices and identified himself with Jesus Christ, or “Arthur Jesus,” who came on earth to judge the dead and the living.

Bispo produced a considerable body of work during his confinement, mostly using material he was able to gather in and around the asylum. Among other objects, he constructed fabric banners with complex embroideries, furniture, ships, and other assemblages, which would survive the apocalypse and ensure his redemption before God. The artist created sculptures composed of everyday items, like tapes, forks, knives, pieces of fabric, shoes—things which he could gather from his surroundings. One series of works, posthumously classified as “O.R.F.A.” and displayed in this exhibition, presents objects wrapped in blue threads, which the patient collected from hospital fabric, also called “mummified” or “embalmed” objects.1 In total, more than 800 objects were preserved after his death in 1989. As if responding to an inner catastrophe, Bispo balanced this turmoil by redesigning his environment, immersed in his constructions.

Quoting Bispo’s testimonial to Hugo Denizart in the 1982 documentary film O Prisioneiro da Passagem [The Prisoner of Passage], the exhibition offers “all existing materials on earth” seen through the prism of Bispo’s apocalyptic vision. Everyday objects removed “from their original places and functions,” as the exhibition text puts it, reveal “the true nature of things” amidst the artist’s “encyclopedic account.” The exhibition presents these objects in three rooms, respectively featuring garments, embroidery banners, and objects which densely populate the space. Its display alludes to Bispo’s psychiatric environment only on its walls, the lower halves of which have been painted purple—a general hygienic dispositive of anonymous public spaces, which serves to protect the walls from patients’ bodies and the traces they might leave.

In this sense, the show follows the path of Bispo’s reception via the Brazilian curators Frederico Morais or Paulo Herkenhoff, who recontextualized his “conceptual consistency” and “visual language” in the frame of artistic experiments ranging from the Fluxus and Arte Povera movements to Joseph Beuys’s “suppression of the authorship” and Christian Boltanksi’s “territory of denied mourning.”2 For Morais, symptomatically, saving Bispo’s work from vanishing in the psychiatric institutions in which it was produced went hand in hand with assimilating and revalorizing it within the frame of canonical art history.

Is there any other way or place for this work to be acknowledged beyond its displacement from the psychiatric cell to a museum’s white cube? Bispo himself refused “art” as a context or name for his production, never signing his work and absenting himself even from his first show at Museum of Modern Art of Rio in 1982. How to move beyond the encyclopedic account of an “individual mythology” where the singularity of such art has been located since Harald Szeemann and Jean Dubuffet?

The history of the anti-colonial psychiatry of Frantz Fanon and Nise da Silveira, and the “institutional psychotherapy” of François Tosquelles, offer more critical spaces of reflection where an apocalyptic experience of mental symptoms is not separated from political catastrophes, such as wars, colonial violence, disciplinary and psychiatric exclusion.3 Rather than considering “art” as mere occupational therapy, for Tosquelles—in whose clinic in French Lozère Fanon spent a fifteen-month internship—artistic production was crucial to the construction of a new social milieu against the state apparatus. Not only painting or sculpture but also collective use of media, such as filming, publication of an intra-hospital journal, organization of film-clubs and carnivals served as instruments of reconstruction of the fallen, shattered world.

Politicizing madness as creative potential, Fanon and Tosquelles did not displace it beyond the social, historical, and geographical contexts of its “lived experience,” a catastrophic horizon which exceeded both the organicist reductionism of psychiatry and the psychoanalytic frame of an individual, or what Félix Guattari refers to as “two bodies psychology.” Both saw in mental disorders the complex temporality of a culturally constituted apocalyptic experience, and a form of resistance to a given social and political order. This theoretical horizon allows for consideration not only of the singularity of art produced in a psychiatric cell, but also of the complexity of the “Bispo Situation” in its “clear political reach,” as the Brazilian art historian Tania Rivera argues, as “an inaugural milestone of the anti-asylum struggle in Brazil.”4

Analysing the crucial role the ships played in Bispo’s oeuvre, the Brazilian media theorist Marlon Miguel sees these as “surfaces of re-inscription of histories, memories, marks” that belong not only to the subjective past of the patient or his personal myth.5 Rather than merely preparing for redemption, the objects displayed at Americas Society present processual cosmologies of reconstructing memory, alluding to a repressed history: the history of the Atlantic Ocean and the transatlantic slave trade. They incorporate but also gesture beyond the patient’s individual experiences, transfiguring the consequences that he himself suffered as a Black person in Brazilian society into a larger, collective archive. In this sense, they constitute traces of historical catastrophes inscribed into the fabric of a new, apocalyptic narrative to come.

Emanoel Araújo, et al., eds., Arthur Bispo do Rosário, trans. Regina Alfarano (Rio de Janeiro: Réptil, 2012), 160–62.

Paulo Herkenhoff, “The Longing for Art and Existing Material in the World of Men,” in the exhibition catalogue Lázaro, Arthur Bispo do Rosário: Século XX (Rio de Janeiro: Réptil Editora, 2012), 140–183.

In particular recent exhibitions, such as “Francesc Tosquelles: Like a Sewing Machine in a Wheat Field” curated by Carles Guerra and Joana Masó at Reina Sofia, Madrid, open a larger frame of critical psychiatry reconsidering the Art Brut movement in this context. See also La Déconniatrie—Art, exil et psychiatrie autour de François Tosquelles, ed. Carles Guerra and Joana Masó (Paris: Arcadia, 2021), and Camille Robcis, Disalienation: Politics, Philosophy, and Radical Psychiatry in Postwar France (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2021).

Tania Rivera, “The Bispo Situation: Art and Insanity in Brazil,” in Bispo do Rosario – eu vim: aparição, impregnação e impacto (Sao Paulo: Itaú Cultural, 2022), 282.

Marlon Miguel, “Representing the World, Weathering its End: Arthur Bispo do Rosário’s Ecology of the Ship,” in Weathering: Ecologies of Exposure, ed. Christoph F. E. Holzhey and Arnd Wedemeyer, Berlin: ICI Berlin Press, 2020, pp. 247–76, here p. 265