Given the current political situation in Turkey, I wouldn’t have been surprised if the curators of this year’s Istanbul Biennial, Berlin-based artist duo Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset, and IKSV, the corporate-funded foundation organizing the event, had decided to call the whole thing off. Since its first edition in 1987, the biennial has weathered numerous crises in Turkey. But this time, things are especially grim: in the wake of the attempted coup in July 2016, political purges have antagonized the country under the authoritarian rule of President Erdoğan. Tens of thousands of university teachers, hospital doctors, and judges have been dismissed while not only dozens of members of parliament have been imprisoned, but also hundreds of journalists. Artists have also been targeted, usually based on sweeping allegations…

The 15th Istanbul Biennial, curated by the Scandinavian artist duo Elmgreen & Dragset, explores what it means to be a good neighbor by constructing a model neighborhood. Hosted by six venues within the city’s cultural district, and showcasing the relatively modest number of 56 artists, the biennial foregoes spectacular individual gestures, dispersed presentations, and extravagant curatorial statements. 1 Instead the works are arranged into a network of small, variously themed communities, each of which relates to and informs the other. Conceived as a microcosm of society, “a good neighbour” is liberal in its politics, decentralized in its allocation of resources, and diverse in its opinions. It is also reliant on its public institutions,…

Given the current political situation in Turkey, I wouldn’t have been surprised if the curators of this year’s Istanbul Biennial, Berlin-based artist duo Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset, and IKSV, the corporate-funded foundation organizing the event, had decided to call the whole thing off. Since its first edition in 1987, the biennial has weathered numerous crises in Turkey. But this time, things are especially grim: in the wake of the attempted coup in July 2016, political purges have antagonized the country under the authoritarian rule of President Erdoğan. Tens of thousands of university teachers, hospital doctors, and judges have been dismissed while not only dozens of members of parliament have been imprisoned, but also hundreds of journalists. Artists have also been targeted, usually based on sweeping allegations ranging from insulting the president to supposedly supporting Kurdish terrorism: in March, the painter Zehra Doğan was sentenced to two years and ten months in prison for a picture in which she painted Turkish flags on buildings destroyed by the Turkish army in the Mardi province, a Kurdish region of Turkey; and in August the writer Doğan Akhanlı, who is a German citizen, was briefly detained in Spain due to an Interpol warrant issued by Turkey, before being released again. Despite such cases and the overall oppressive political development, the curators and the foundation decided to go ahead, making this biennial a highly, and skeptically, anticipated one: how would it bear up against its current moment—let alone tackle increasing limitations to free expression?

Dragset and Elmgreen’s title for the biennial, “a good neighbour,” may at first sound banal, harmlessly domestic. But over the course of the exhibition the implied question—what makes a good neighbor, and a bad one?—becomes increasingly pertinent and far-reaching. One of 30 newly commissioned pieces in this modestly sized edition featuring 56 artists, Pedro Gómez-Egaña’s Domain of Things (2017) sets the pace with its brooding yet subdued atmosphere. Upon entering the Greek Primary School—five venues of the biennial including this one are in the central Beyoğlu district, and one is in neighboring Fatih—you encounter a small living space with no walls, the furniture dimly lit by desk lamps. Underneath the fragmented wooden floor, you can only just make out a number of performers moving sluggishly like sleuths in scaffolding, as if awaking from a stupor, slowly but steadily moving the scene above them around. It’s hard not to think of something I’ve heard several times about artists and protagonists of the Turkish art scene: that a number of them, depressed by the outcome of the Gezi Park protests of 2013 and the developments since the attempted coup, have retreated into privacy. But Gómez-Egaña’s piece seems to suggest that that state of retreat is not terminal, that under the surface, things are stretching and contracting as if working at again coming forth.

Politically charged symbolism made bearable by modest minimalism continues with Lungiswa Gquanta’s field of broken Coke bottles filled with green-tinted petrol (Lawn 1, 2016/17), as if weaponizing the image of the proverbial front lawn of middle class homes—a trenchant statement coming from someone who has grown up in a township in post-apartheid South Africa. The realism of a four-minute film by Erkan Özgen (Wonderland, 2016) is even more concrete and heart-wrenching: a deaf 13-year-old refugee boy recounts the horrific killings he witnessed on his flight from Syria with urgent pantomime. Özgem shows and tells radically less than any ordinary reportage would, but achieves just as much if not more.

“neighbour” takes on a dark tone in the context of civil crisis and war: your neighbor might be the one who denounces you, kills you. Or maybe you yourself are the informer. Comic relief is needed—not to soften the blow, but on the contrary, to make it more felt by way of contrast. Jonah Freeman and Justin Lowe’s five-room installation Scenario in the Shade (2015–17) at first seems a nerdy-filthy scenario à la Christoph Büchel, but then the atmosphere increasingly turns towards psychedelic comedy: all day-glo and dadaist humor, especially with fake DVD cases of fictional movies (with cover illustrations that present a James-Bond-style thriller titled “Ghastly Art Practices,” or “Beatniks are left to die alone,” apparently a silly animation for four-year-olds). The entire scenario evokes fictional Pacific Rim subcultures based around style and intoxication, and the feature-length video The San San Trilogy (2014–16) drives that evocation home with a mind-blowing array of shots that are effectively psychedelic-sculpture-as-film.

Often in this biennial, similarities amongst works alternate with stark contrasts—a sense of rhythm and pace courtesy of the artists-as-curator duo. Two juxtapositions at Istanbul Modern museum offer a case in point. Rayyane Tabet’s grid of marble and concrete columns sourced in Beirut, testifying to the fragmented and traumatic built history of that city (Colosse au Pied d’Argil, 2016), is the perfect complement to Alper Aydin’s pressing of chopped trees into a corner with a bulldozer blade (D8M, 2017), prompted by recent clearings for a new Istanbul airport. Adel Abdessemed’s rendering of the naked girl running away from napalm in Nick Ut’s iconic 1972 Vietnam war photograph as a lifesize freestanding sculpture (Cri, 2015) is a low point of the biennial—which is immediately remedied by the nearby work of Latifa Echakhch. Whereas Abdessemed plays out a calculated provocation by having the figure made in ivory (what’s next? A dying Biafra baby in ebony?), Echakhch, who also based her work on reportage imagery but of masses demonstrating, has painted a mural that she then defaced (Crowd Fade, 2017). The people depicted, many of them wearing gas masks, inevitably evoke the Gezi Park protests, even though there are no signs or flags. With the pieces on the floor and fragments on the wall, the work testifies to the shattering of hope, to the disenchantment of the language of the political mural—and not least to the possibility of pointing towards things without expressly saying them: in July, Erdoğan announced another three-month prolongation of the state of emergency established a year ago, which entails the suspension of any right to assemble and demonstrate.

In Turkey, homosexuality is legal, but there are also no anti-discrimination laws, and assaults, rapes, and even murders of members of the LGBTQ community are often ignored or only lightly investigated. This is the background against which Mahmoud Khaled developed his ambitious project Proposal for a House Museum of an Unknown Crying Man (2017). But the initial story that prompted it is of an incident in Cairo in 2001, where 52 men arrested on a gay disco boat were imprisoned, beaten, and taken to court, where many of them hid their faces behind white tissues. One, with his face not fully covered, was photographed crying, and the press image became iconic in the Egyptian gay community. Khaled has transformed Ark Kültür, an art center located in a Bauhaus-style 1930s residential house, into the elaborately fictionalized home of that crying man. Having gone into exile in Istanbul, he lives the life of a sophisticated but utterly melancholic dandy. A glass cabinet in his living room contains no family photos, but rather framed close-up shots of brushwork in the cruising area of a park; on his piano, he has placed multiple pictures of a crying boy—a common kitsch motif originating in the 1950s. In his winter garden shower, a monitor continuously plays a seven-minute scene from Maher Sabry’s movie All My Life (2008), which is credited as being the first Egyptian movie openly addressing the subject of homosexuality, including the case of the Cairo 52. Like in Orhan Pamuk’s nearby Museum of Innocence, which houses a permanent exhibition of objects from the 1970s related to Pamuk’s novel of the same name from 2008, Khaled provides an audio guide that makes the display part of an overarching narrative of sorrow and remembrance of things past. But in contrast to Pamuk’s nostalgia for a bygone era, his proposal extends from the recent past into a poignant now.

Not all works or venues reached such a level of aesthetic accuracy and narrative ambition; the display at the Pera Museum, for example, felt less well thought through than the one at the Greek School. But even if works such as Echakhch’s or Khaled’s implicitly address current political issues, the skeptical beholder may well think: does that suffice in a country where basic civil rights are explicitly denied on the basis of emergency rule, while increasing autocratic powers are awarded to its president? Does a biennial in the current situation inadvertently provide a cultural fig-leaf? It’s a tricky question with no simple answer. Among those familiar with or part of the Istanbul art scene, some I’ve come across take this as an opportunity to remind me that Koç Holding, the main sponsor of the biennial, is part of the military-industrial complex (Koç, a huge conglomerate which in 2013 was responsible for 9 per cent of Turkey’s annual GDP,1 does have a subdivision producing armored military vehicles, as Hito Steyerl already pointed out with Is the Museum a Battlefield? [2013]; strangely however, those who four years later take a cue from Steyerl’s contribution to the 13th Istanbul Biennial to question participation in the 15th edition otherwise don’t seem to mind that, say, Germany’s biggest arms-producing company Daimler Benz, a major art and culture sponsor, doesn’t experience the same scrutiny). Others insist that especially at this time the biennial needs to be attended and participated in as part of what keeps culture and critical thinking going.

To pounce on the fact that the biennial is sponsored by corporations in a country where there is literally no contemporary art institution financed by public money (even the left-wing art center Depo can only exist through the support of left-leaning millionaire Osman Kavala) feels somewhat cynical. The Turkish government has more or less shut the door on civil society; to help wedge that door back open, to let air in and help civil society to continue and recover, the curators and the artists included have made the compromise of refraining from explicit comments on the current political situation and open attacks on the powers that be. However, as long as they manage to address that political situation at least indirectly through powerful artworks that any sensible person can read and understand as critical comment, going ahead with such a biennial in such times is, I think, provisionally justified. But only if the ultimate goal remains to (re-)establish freedom of speech. As the biennial is not over yet, statements to that effect can still be made.

“Turkish businesses targeted after Erdogan comments,” Financial Times, September 13, 2013. https://www.ft.com/content/4093e50a-1c8b-11e3-a8a3-00144feab7de

The 15th Istanbul Biennial, curated by the Scandinavian artist duo Elmgreen & Dragset, explores what it means to be a good neighbor by constructing a model neighborhood. Hosted by six venues within the city’s cultural district, and showcasing the relatively modest number of 56 artists, the biennial foregoes spectacular individual gestures, dispersed presentations, and extravagant curatorial statements. 1 Instead the works are arranged into a network of small, variously themed communities, each of which relates to and informs the other. Conceived as a microcosm of society, “a good neighbour” is liberal in its politics, decentralized in its allocation of resources, and diverse in its opinions. It is also reliant on its public institutions, occupying buildings which originally served educational, social, cultural, and residential purposes.

No one attending the opening week, which took place under the extended state of emergency that entitles the authorities to arbitrarily detain any citizen for five days without recourse to a lawyer,2 could mistake these values for those of the incumbent Turkish government. Whether consciously or not, the biennial is shaped by the studied banality of its curatorial statement, with its implication that we should all just get along, and the highly charged atmosphere in which it is set. Beyond the armed guards and metal detectors that accompany any gathering of foreign nationals in Istanbul, Michael Elmgreen’s insistence at the press conference that this exhibition was grounded in the domestic risked sounding like a failure to acknowledge the elephant in the room. At worst, it could be taken for quietism.

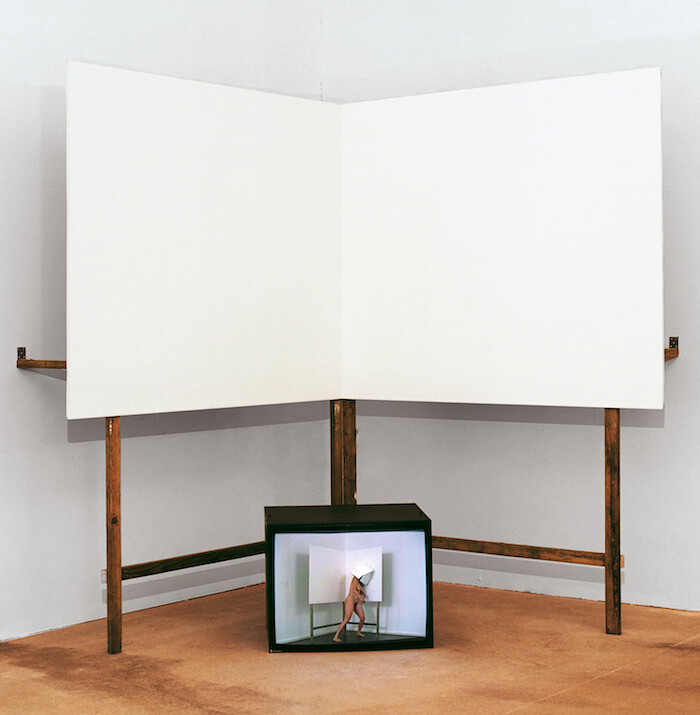

That accusation relies on the assumption that politics is played out on the grand stage. Yet, as even a cursory engagement with the exhibition makes clear, the home is the cradle of wider conflicts as much as a refuge from them. On the fourth floor of the Pera Museum, best known for its collection of stately nineteenth-century Ottoman art, Louise Bourgeois’s photogravure Femme Maison (1946-7) depicts a naked woman with the head of a house: her mind trapped, her sex exposed. The drawing inspired Monica Bonvicini’s nearby Hausfrau Swinging (1997), for which an actor playing Bourgeois’s hybrid creature was filmed violently banging her housebound head against a drywall corner. That women are imprisoned in the home is not, under a government that last year supported a bill pardoning child rapists who agreed to marry their victims, an apolitical statement.3 By suggesting that the same fundamental structures operate at the micro- and macropolitical scale, the curators propose a strategy predicated on addressing the latter through the former.

The juxtaposition of these two works, separated by half a century, is a reminder that communities operate through time as much as space. Also at the Pera Museum, Andra Ursata’s shoebox dioramas put forward a history written from below: a social, domestic, and feminist perspective. Her recreations of the house in which she grew up describe a history of Romania through the living conditions of its laboring class; it seems pertinent that its street was named for a revolutionary hero, one of the “great men” around whom conventional historical study is arranged. Where the walls of T. Vladimirescu Nr 5, Sleeping Room (2013) are lined with religious tapestries reproducing scenes from the life of Christ, the windowless concrete cells of Beijing’s migrant workforce, as pictured in Sim Chi Yin’s Rat Tribe (2011–14), are decorated with glossy posters for movie melodramas and advertisements for consumer products. It is difficult to imagine a more eloquent illustration of the fact that however the ideologies and geographical centers of power might shift, the conditions of those exploited by it remain the same.

That the rooms in China are occupied, and those in Romania empty, suggests the global movement of populations in search of work. The absence of inhabitants from the households they have constructed is a striking feature of the biennial, and prompts reflection on the various forms of—and reasons for—the displacement of people from their native lands. At Ark Kültür, Mahmoud Khaled’s Proposal for a House Museum of an Unknown Crying Man (2017) portrays a man exiled from his own society though the new home he has created. The installation imagines that the eponymous “crying man”—one of 52 Egyptians charged with “contempt of religion” and “debauchery” for attending a 2001 party at a gay nightclub in Cairo—has taken refuge in Istanbul, and installs him in an elegant European townhouse through which echoes Jacques Brel’s Ne me quitte pas (1959). The artist collective Yoğunluk, in their site-specific installation The House (2017), also use absence and song to comment on the persecution of minorities, in this case the Greek Orthodox community forced out of Istanbul by religious intolerance and the confiscation of its properties.

That displacement is felt most keenly in the historic Greek School’s closure and conversion into an exhibition space, where each artist is afforded an empty classroom. The unstable structures on which the idea of home is built are literalized by Pedro Gómez-Egaña’s Domain of Things (2017), which resembles a stage set for a one-act domestic psychodrama—dining table, bed, kitchen—awaiting its actors. These stage boards are crazed with cracks that, when seen from the mezzanine level, appear mysteriously and arbitrarily to widen. From ground level it is possible to peer into the dim tangle of steel scaffolding that supports the raised stage and see a man clambering around, pulling and pushing its movable sections together. The work reconciles personal memories of childhood (Gómez-Egaña grew up in a region of Colombia prone to earthquakes) with a Freudian vision of a conventional family home built on barely repressed energies. Elsewhere in the most impressive of the biennial’s venues, Jonah Freeman and Justin Lowe’s immersive, retro-futuristic installation Scenario in the Shade (2015–17) and Andrea Joyce Heimer’s narrative paintings of her fractious hometown use childhood memories to explore ideas around belonging and community.

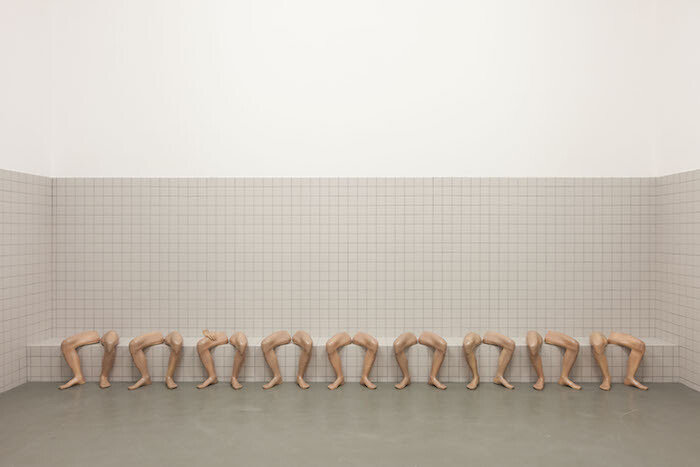

Istanbul Modern is the most uneven of the main sites, and hosts both a standout work—Candeğer Furtun’s sculptural installation Untitled (1994-96), which lines up nine pairs of disembodied male legs in a tiled room resembling a hammam—and its most significant misstep, Adel Abdessemed’s crass Cri (2013). A sculpture in ivory of photojournalist Nick Ut’s powerful image of a 9-year-old girl fleeing napalm in 1972, Abdessemed’s work translates a photograph—credited with hardening US public opinion against the Vietnam War and even hastening its end—into a cheap provocation. The irony is that its supposed critique of the commodification of trauma is itself addressed to a narrow audience, while its obvious offensiveness will alienate others. It nonetheless serves the curators well, offering support by counterexample for a strategy which elsewhere addresses “big issues” by implication and allusion.

Furtun’s work—in which the disembodied limbs serve as metonyms for Turkey and each of its eight neighbors—exemplifies that policy. The Istanbul-based artist uses the awkward posturing of men in a social situation, their legs firmly planted and their muscles (it seems reasonable to infer) flexed, to poke fun at the competitive machismo that characterizes international relations. The work offers a reminder that men who seek absolute power, here pointedly deprived of their manhoods, are typically more sensitive to ridicule than either political reason or appeals to their conscience. In a direct comparison of these two pieces, the symbolic approach—which allows the visitor the intellectual space to interpret and thereby to participate in the critique—is not only more sophisticated but more telling.

Which isn’t to say that this is always the case. It is my practice to take notes when visiting exhibitions I have been commissioned to review, jotting down impressions and interpretations which I can later develop. Emerging from the Kurdish artist Erkan Özgen’s Wonderland (2016), situated away from the bustle of the biennial in a black box on the top floor of the Greek School, I put my pen and paper away. In this 4-minute video, a deaf 13-year-old boy named Mohammed acts out in mime the atrocities committed against members of his family during the siege by Islamic State of his hometown of Kobanî, now Rojava. It is a simple work—albeit intelligently edited, lit, and located in the context of the biennial—but like all human suffering of this magnitude defies description in any language other than the victim’s.

If good fences make good neighbors, then society is less about dismantling or erecting walls than ensuring that their design protects the weak from the strong. By choosing to focus on neighborhoods, the curators of the Istanbul Biennial risk distracting from the erosion of those institutions that protect them, whether the rule of law, freedom of expression, or the democratic process.4 “a good neighbour” flirts with both the tendency towards isolationism it professes to resist—conservative politicians are apt to put the community to which their constituency belongs “first”—and rank sentimentalism—by suggesting that art might transcend boundaries. But in its structure and selection of works the biennial establishes the neighborhood as an effective metaphor for wider structural relations. It reminds us that not only are bodies and communities the places where political injustice is most keenly felt, they are the sites from which change can come.

The effects of the closure of major players in the Istanbul art scene have been exacerbated by the relocation of several galleries to new parts of the city in the wake of the attempted coup in 2016. The reputation of the nearby Taksim Square as a rallying point for anti-government forces has seen new restrictions placed on buildings in the district, while galleries have been the subject of protests (and attacks) from conservative elements. Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s well-received 2015 edition, by comparison, was spread across 30 venues.

Details of the State of Emergency Law, currently on its fourth extension in the wake of the failed coup, can be found on the website of Amnesty International: https://www.amnesty.org/en/countries/europe-and-central-asia/turkey/report-turkey/.

The bill was eventually withdrawn after street protests. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-38061785.

None other than Margaret Thatcher justified her conviction that “there’s no such thing as society” by stating that there are only “individual men and women and there are families. And no government can do anything except through people, and people must look after themselves first. It is our duty to look after ourselves and then, also, to look after our neighbors.” Margaret Thatcher, “Interview for Woman’s Own” (September 23, 1987). https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/106689.