Let us begin with the grid: flat, rational, anti-mimetic, static. The grid, writes Rosalind E. Krauss, “announces […] modern art’s will to silence, its hostility to literature, narrative, discourse.”1 If the grid can be said to represent anything, Krauss argues, it is the two-dimensional surface of the canvas itself. Nine new gouache- and graphite-on-paper works by the Portland-based Ellen Lesperance present us with evidence to the contrary.

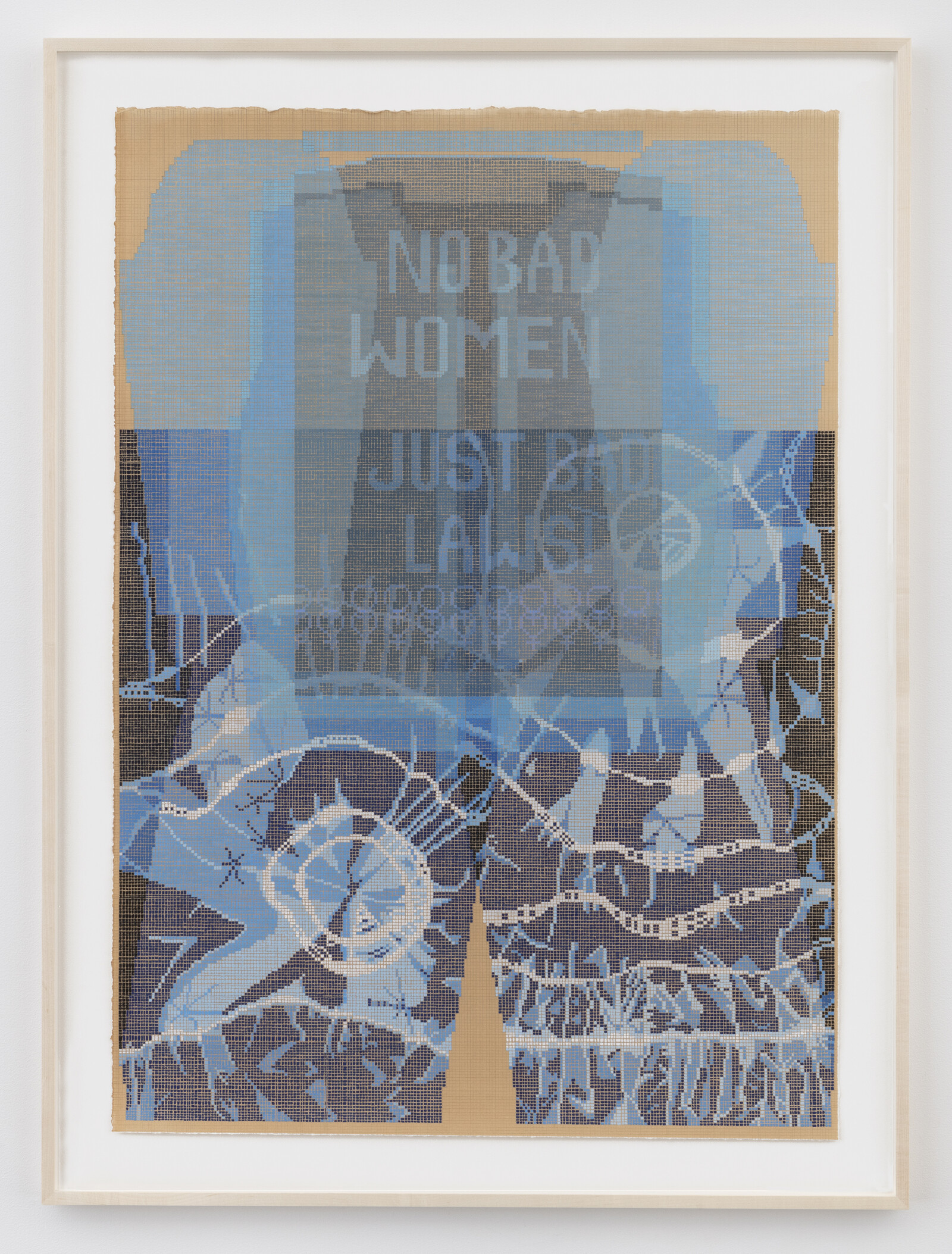

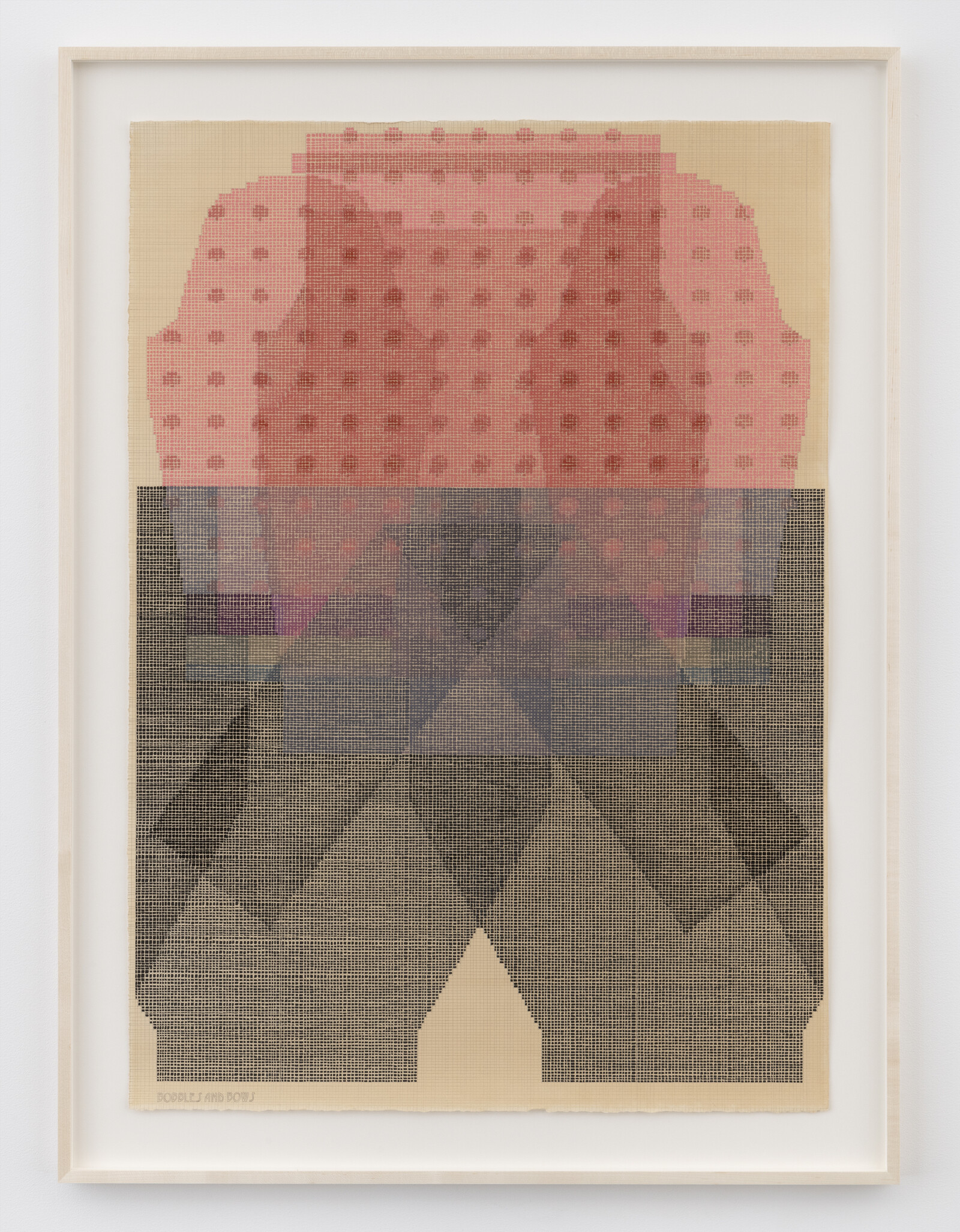

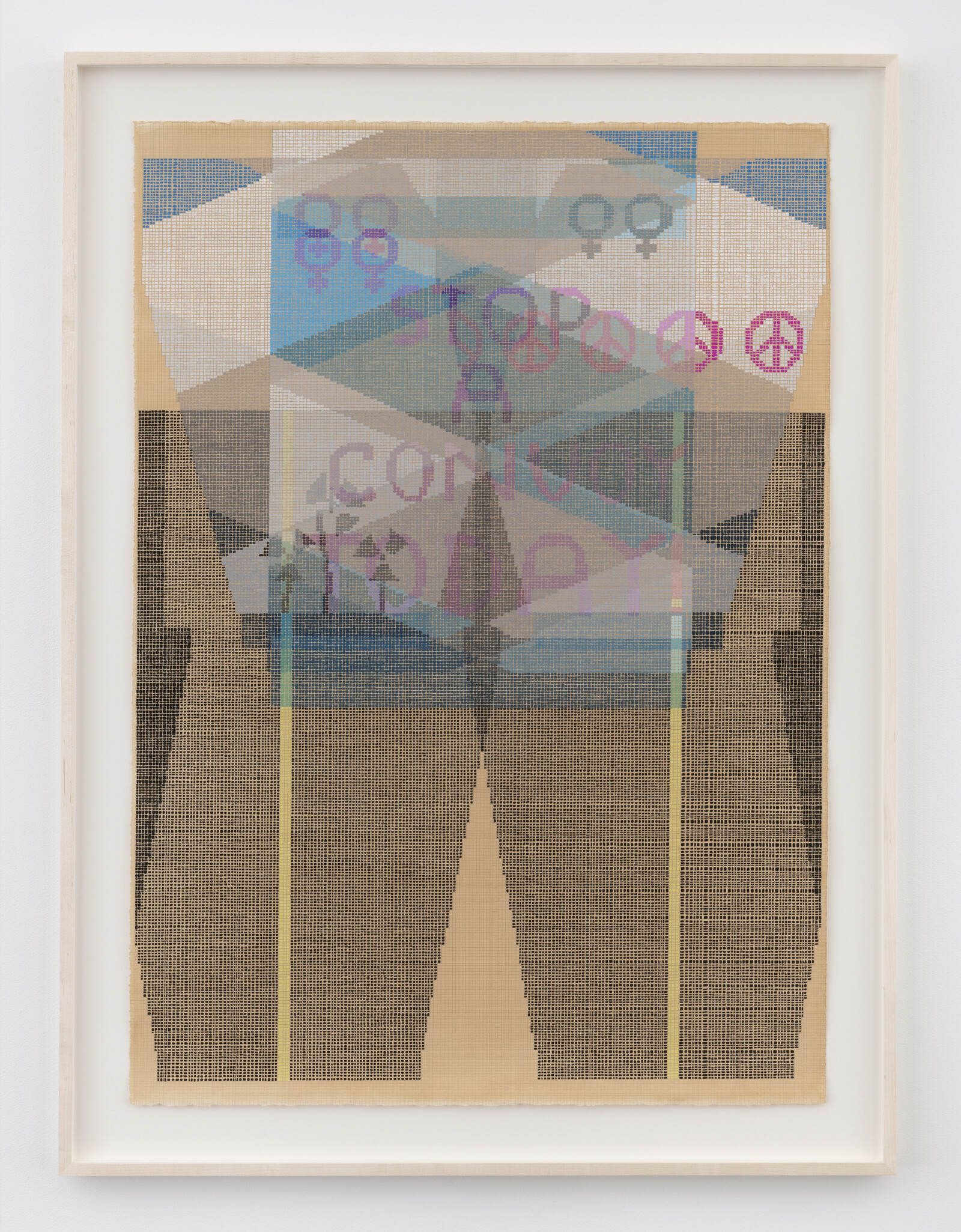

Lesperance’s grids are not austere or empty—the hand-drawn graphite lines hold layered squares of color that combine to produce, from a certain distance, the appearance of tightly woven tapestry. But they are still, insistently, grids—the lines are visible and the shapes emerge from a series of squares whose boundaries are observed. What differs from Krauss’s evaluation here is not the grid itself but its function. These grids speak. Their content is historical, narrative, real. Far from being silent, these artworks are a condensed, formal expression of years of research into feminist, anti-nuclear activism.

In 1981, the Welsh group “Women for Life on Earth” walked from Cardiff to Greenham Common in Berkshire, England to protest the installment of ninety-six Cruise nuclear missiles. The protest turned into an encampment—the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp—that remained on site until 2000 when it was turned into a memorial. The missiles were removed in 1991. The rotating members of the all-female camp engaged in direct action to disrupt the daily operation of the military base; they chanted, ululated, got arrested, and fought many legal battles. They also lived there—some for several years—building shelters that were periodically razed, sharing food, and caring for one another. Lesperance’s research focuses on one aspect of the labor that sustained this act of protest and way of life: the sweaters that the women knitted by hand and wore.

Using documentary photographs of the encampment, Lesperance has translated the real clothing as it appears in these images (the position of the women’s arms, legs, torsos become part of the work) into Symbolcraft—a standardized language for knitting—and turned the resulting patterns into gouache overlays created, point-by-point rather than stitch-by-stitch, in the minute spaces of a hand-drawn graphite grid. The results are both visually and conceptually stunning and complex. Combining the aesthetic pleasure of color field painting, the inexplicable scopophilic compulsion inspired by grids, and the haptic quality of fiber arts into a single composition that also evokes a political tradition is no small feat.

Almost but not quite symmetrical, each work has a revelatory quality that recalls the work of Hilma af Klint. But the revelation here seems more material: rather than divine revelation, they suggest human processes of uncovering. Their resemblance to Rorschach blots evokes the subconscious, while they also display a perceptible affinity with anatomical drawings, in which miraculously un-bloody flesh neatly peels back to reveal internal organs. Bodies, after all, are Lesperance’s primary interest. She has repeatedly stated that the animating spirit of her formal decisions was a desire to represent women while evading the patriarchal legacy of figurative painting. Instead of a body, we’re shown a trace of a bodily presence that is, in another move away from conventional figurative work, both articulate and actively involved in the artistic production of its own representation. By choosing an object produced by the subject (the sweater) as a stand-in for the subject’s body, Lesperance has found a new way to represent the subject herself: a self that is here defined as a thinker, maker, and member of a community. This particular form of collective subjectivity is repeated in the artist’s production of actual sweaters, designed to be shared among and worn by women as they engage in political activity.

This is not to say that Lesperance’s subjects aspire to the disembodiment that might be implied by the grid’s association with a Cartesian notion of being, wherein consciousness is independent of matter. It was real human bodies that Women for Life on Earth were both defending and using as a defense. To choose a physical covering as a stand-in for a person suggests a desire or ability to defend real, vulnerable bodies: we could easily be looking at a schematic rendering of multi-colored armor, or an exoskeleton.

The grid, of course, has many implications that do not support what Krauss terms “modern art’s will to silence,” that refuse opposition to nature or the real. One of the grid’s early uses was in mapping. The utility of the grid as a tool to help achieve mathematical perspective in painting was not unrelated to its use as a navigational aid during Europe’s first great age of exploration. The newly discovered technologies of sight and representation, and the colonial conquest that marked the sixteenth century, find an easy parallel in nuclear proliferation. The electron microscope, a technology for seeing and representing the world, was key to the invention of a bomb that dramatically increased the geographic scope of domination. Embedding the grid within these traces of bodies also suggests a spectral remnant of colonial power in the bodies of the protesters themselves, as well as evoking the ways that technology—in this case nuclear power—not only acts on bodies but constitutes them.

Grids, pace Krauss, may be silent, oblivious to the ways in which real objects relate to one another in space and time, but this ignores one of their primary functions, that of translation from one dimension to another—the capacity to turn a drawing into a building and, conversely, transpose a three-dimensional object onto a plane. Or, in the case of Lesperance’s work, from live body to photograph, photograph to painting, painting to knitted object—an object, furthermore, that changes shape and takes on volume when placed over a live body. Lesperance’s work reveals the grid’s ability to move meaning and form back and forth across physically incompatible realms; the articulate potential of its deceptively simple format; the volumes contained in its dense history as cartographic and military device. “Together we lie in ditches and in front of machines” is one of many pieces of text gathered from the commune’s archives that Lesperance has used to title these works. In the sentence’s stark arrangement of nouns and prepositions, we might see a set of relations easily plotted on a grid. But just as easily we might see a wholly new form of mapping.

Rosalind Krauss, “Grids” in October, vol. 9 (1979), 50.