Mahmoud Khaled has in recent years taken the house museum—a space dedicated to the legacy of the person (real or invented) who lived there—as his medium. Beginning with “Proposal for a House Museum of an Unknown Crying Man” at the 15th Istanbul Biennial in 2017,1 Khaled has used these imagined sets to explore the violence and power of memorialization. In his first UK solo exhibition at The Mosaic Rooms, “Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost it,” the Berlin-based, Egyptian artist transforms the gallery space into a domestic setting. This immersive environment—featuring murals, sculpture, photography, a sound piece, and an artist’s book—imagines the life of the anonymous owner of a misplaced phone in order to commemorate it. This project builds on Khaled’s continued interest in museums and archives as apparatuses of history-telling that can be reappropriated to document and celebrate marginalized queer lives. His work examines the tension between the public and the private, as well as the relationships between identity, anonymity, and intimacy.

Dina Ramadan: Your first use of the form of the house museum memorialized a character you call the “unknown crying man.” Who was this figure?

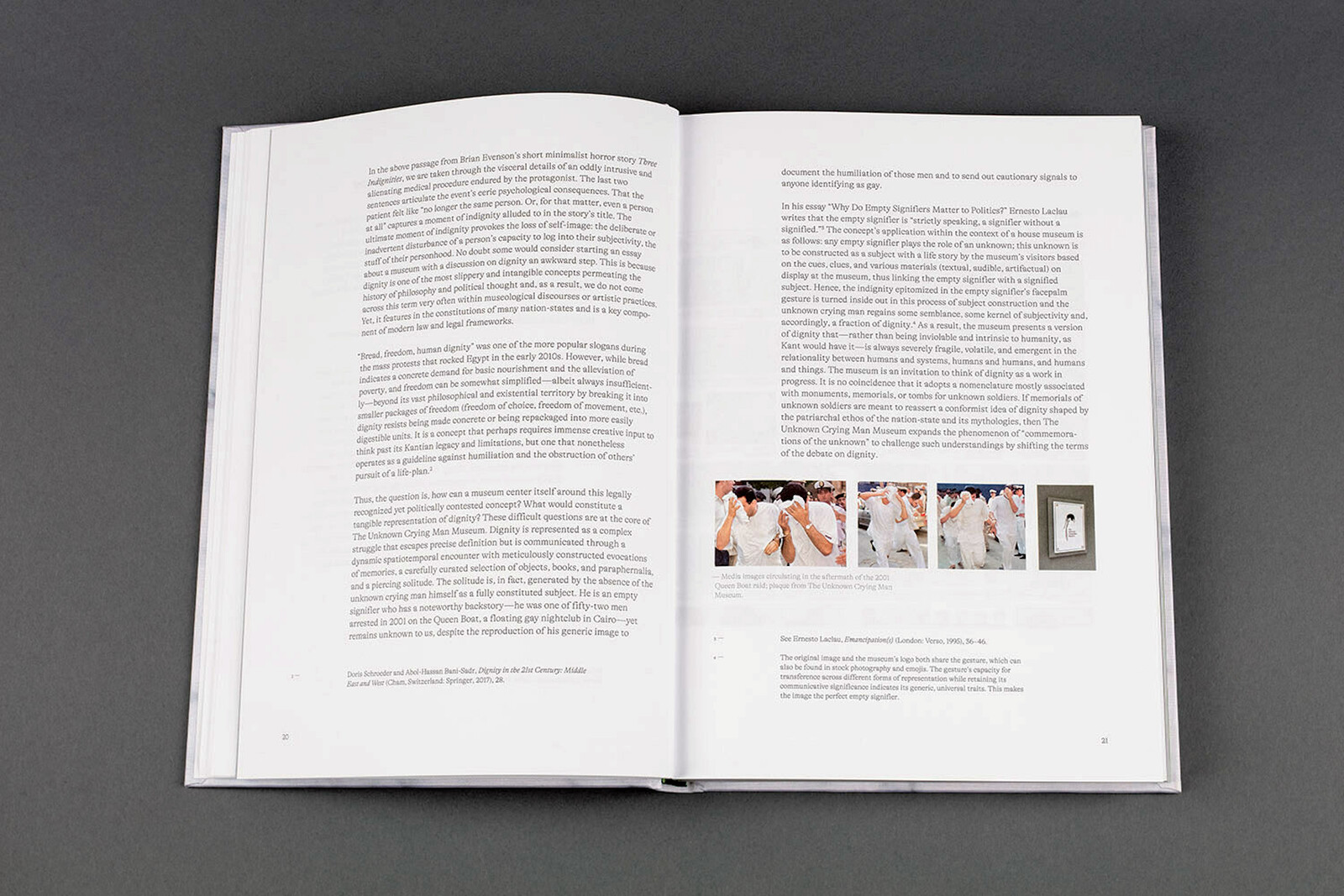

Mahmoud Khaled: The image that started this whole project is a “poor image” in that, in itself, it has no visual-contextualizing information. It is an abstracted photograph of a weeping man dressed in white, hiding his face with white cloth. We don’t see his identity. There is no indication of when or where the photograph was taken.

In fact, it first appeared in the Egyptian press in May 2001, following the arrest of 52 men on a boat on the Nile which was hosting a party for gay men who were subsequently charged with “obscene behavior” and “contempt of religion.”2 This anonymous figure was, presumably, one of these persecuted men. Despite the poverty of this image, it has managed to sustain a position of authority for more than 20 years and gain an economic value within the ecosystem of photojournalism. For example, any news agency writing a piece about homosexuality in Egypt used this image to illustrate their texts. It became a stock image, representative of a larger community.

I wanted to unpack the complexity of this image, my relationship with it, and reflect on the moment when a person becomes known for being unknown, when remaining unknown becomes an act of political resistance to the state violence of outing people through an orchestrated media spectacle.

DR: Why did you choose to work with the house museum as a medium of memorialization, given that anonymity is such a crucial aspect of the unknown crying man? How does this challenge the form of the house museum?

MK: There is a strong contrast between the medium and the subject of the work that made the conceptual process intense and exciting. Naturally, a house museum cannot be created for an unknown person, as part of its mission as an institution is to celebrate and commemorate that person and their legacy. Building a museum for an unknown person is an absurd act, but I was seduced by its absurdity, and this generated a lot of questions throughout the process. How do we commemorate an unknown person? How do we write an invisible history?

The work celebrates anonymity and privacy in a form that is all about transforming the private into the public. These paradoxes are what inspired the methodology.

DR: I was thinking about the parallels between the public/private space of the house museum, and in your upcoming exhibition, “Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost it,” the assumed privacy of someone’s phone found in a public bathroom. In both cases someone’s private material is suddenly made very public.

MK: There’s nothing more interesting for me in contemporary life than the tension between public and private. This new exhibition is a portrait of a fictional man reconstructed from the contents of a mobile phone he left in a public toilet.

The idea for this project began with “Fantasies on a Found Glove, Dedicated to the Lady Who Lost it” (1878) by Max Klinger, which consists of ten etchings that document and celebrate his obsession with an unknown lady based on a glove she lost at a skating rink. The drawings are fantastical, and left a strong impression on me, as they capture the artist’s pain and struggle with love, longing, loneliness, and paranoia, all instigated by insomnia. After experiencing this piece for the first time, I wondered what Klinger would do if he was living in our contemporary moment and found a mobile phone instead of an elegant glove.

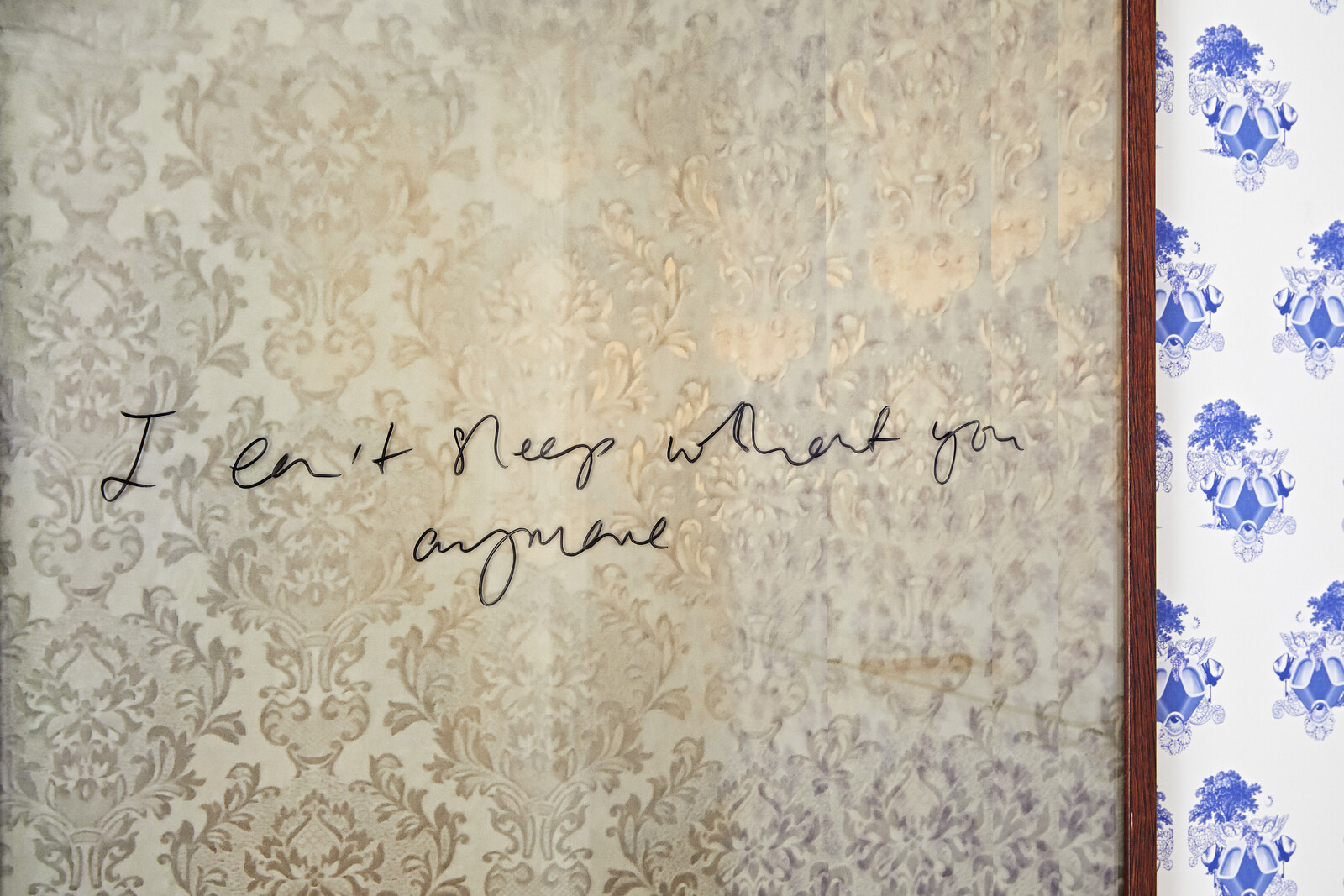

The exhibition stages a domestic environment that reflects the personality of the phone’s owner, someone who is very erotic, elegant, but—as the sleep-aid apps found on his phone suggest—troubled. I imagined that the phone was found in a public bathroom, a space where men enjoy the pleasures of being alone and together, a place that is simultaneously public and private. It is a liminal space, with an unspoken code.

I had a strong desire to move beyond “Proposal for a House Museum of an Unknown Crying Man” because the story behind it is very emotionally and politically loaded. I wanted to use what I’ve learned from this work, but in a form that doesn’t really belong to a specific time and place, a certain city or a certain political moment. It’s just a man who lost his phone in a public toilet.

DR: One of the connections I see between your work in recent years, whether the house museum or the cell phone, is the different modes of archiving, whether physical, virtual, or imagined.

MK: I trained as a painter in a classical fine arts school, and when I shifted in my practice towards more research-based work, asking for official permission to use an institutional archive was always treated with suspicion. Plus, the closer I get to an official archive, the more potential for an unexpected confrontation with the authorities, with consequences that might limit my creativity and also freedom.

Now, I think not having much access to institutional archives has shaped me as an artist and the way I think of my research. It has given me a lot of freedom. I think of cell phones and private houses as archives: naturally structured and informal ones, without the power of authority and the politics of funding.

DR: And in “Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost it” you are imagining and creating a new kind of archive, one that counters the erasures or silences of the official archives.

MK: My work has been always oriented towards the fictional, the imaginative, and the proposed. I’m playing that role as an artist in these works: trying to imagine the screenshots my friends and I share on our phones from dating apps such as Grindr as a conversation forming an archive.

Although it is very ephemeral and can be very banal, this process does illuminate certain dynamics and relationships between people, and society as a very specific group at a very specific time. I’m always happy to unpack this in my work, as is the case in the artist’s book that will be published alongside my exhibition at The Mosaic Rooms.

So yes, the house is an archive. The phone is an archive. I like how we all carry growing archives around in our hands and pockets.

DR: And A Book On A Proposed House Museum For An Unknown Crying Man is also an archive of sorts? It is not just a monograph. It’s a medium that sits parallel to the exhibition, but isn’t exclusively about the exhibition. It’s in dialogue with it, adjacent to it, but not entirely limited to it.

MK: I think about the book as a performative publication celebrating the collection of a museum that doesn’t exist. I wanted it to participate in the bourgeois tradition of visiting a museum, buying the expensive coffee-table book from the gift shop, and then displaying it in our living rooms. I wanted to see this celebration of a queer museum in middle-class houses, hopefully in Egypt. It is a subtle penetration of the private libraries and living rooms of this specific class.

The physicality of the book is very important to me, conceptually and politically, since queer histories and archives have no material presence in Egypt. I wanted a physical book that would archive, document, and historicize this moment in the Arab/Egyptian queer struggle, even if it is an imagined and proposed history.

DR: How did the editorial process shape the content of this book?

MK: My co-editor Sara El Adl and I imagined the texts to be performative. We wanted the contributors to imagine a moment, 30 or 40 years from now, when someone might decide to commemorate what happened in 2001 and make a museum dedicated to the person in this now-stock image. It gave me the chance to work with people I admired beyond the bubble of contemporary art, in the fields of journalism, academia, human rights, and activism.

DR: There is a melancholy that hangs over both the house and the book, a kind of nostalgia that is reclaimed as a position and a voice to be listened to in a different way. What kind of work is melancholy doing for you, and why do you lean on this affect in your work?

MK: There is something attractive about melancholy as a state of existence, one that is attached to the space of exile. I wanted to create an imagination of a productive exile, for a person who is not constantly longing for home. But there is no way for me to think of exile without melancholy; it is part of being exiled. You can turn exile into something productive, but melancholy remains inescapable.

Mahmoud Khaled’s “Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost it” is on view at The Mosaic Rooms, London, through September 25, 2022.

“Egypt: Egyptian Justice On Trial - The Case of the Cairo 52”, OutRight Action International, October 15, 2001, https://outrightinternational.org/content/egypt-egyptian-justice-trial-case-cairo-52.