I am standing in front of two full-length portraits, each just over 200 centimeters tall. The one on the left is a gray-scale screen print; in it, a man in a billowy shirt with a popped collar, jeans, and cowboy boots has emerged from the void to draw a revolver from the holster at his hip, which he points at the viewer. The one on the right is painted in thick, dark oils; it shows a man in a black three-piece suit and polka dot tie, his hands in his trouser pockets, standing in his study, before wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling bookshelves and a desk covered in a red, tasseled table cloth, on which the viewer can make out two candlesticks and a set of miscellaneous papers. The subject of the first painting is Elvis Presley. The subject of the second: Vladimir Lenin.

These two portraits—Andy Warhol’s Elvis Presley (Single Elvis) (1964) and Dmitriy Nalbandyan’s Lenin (1980–82) respectively—flank the entrance of “The Cool and the Cold: Painting in the USA and the USSR 1960-1990,” a selection of over 125 pieces from the collection of the late chocolate manufacturer and art historian Peter Ludwig and his wife Irene, now on view at the Gropius Bau in Berlin Mitte. Curated by Benjamin Dodenhoff and Brigitte Franzen, sponsored by the German Federal Minister for Foreign Affairs and the US Embassy, and located in a building once adjacent to the Berlin Wall, the exhibition is a study in “critical juxtaposition,” whose overarching theme is that curious episode in recent geopolitical history we call the Cold War.

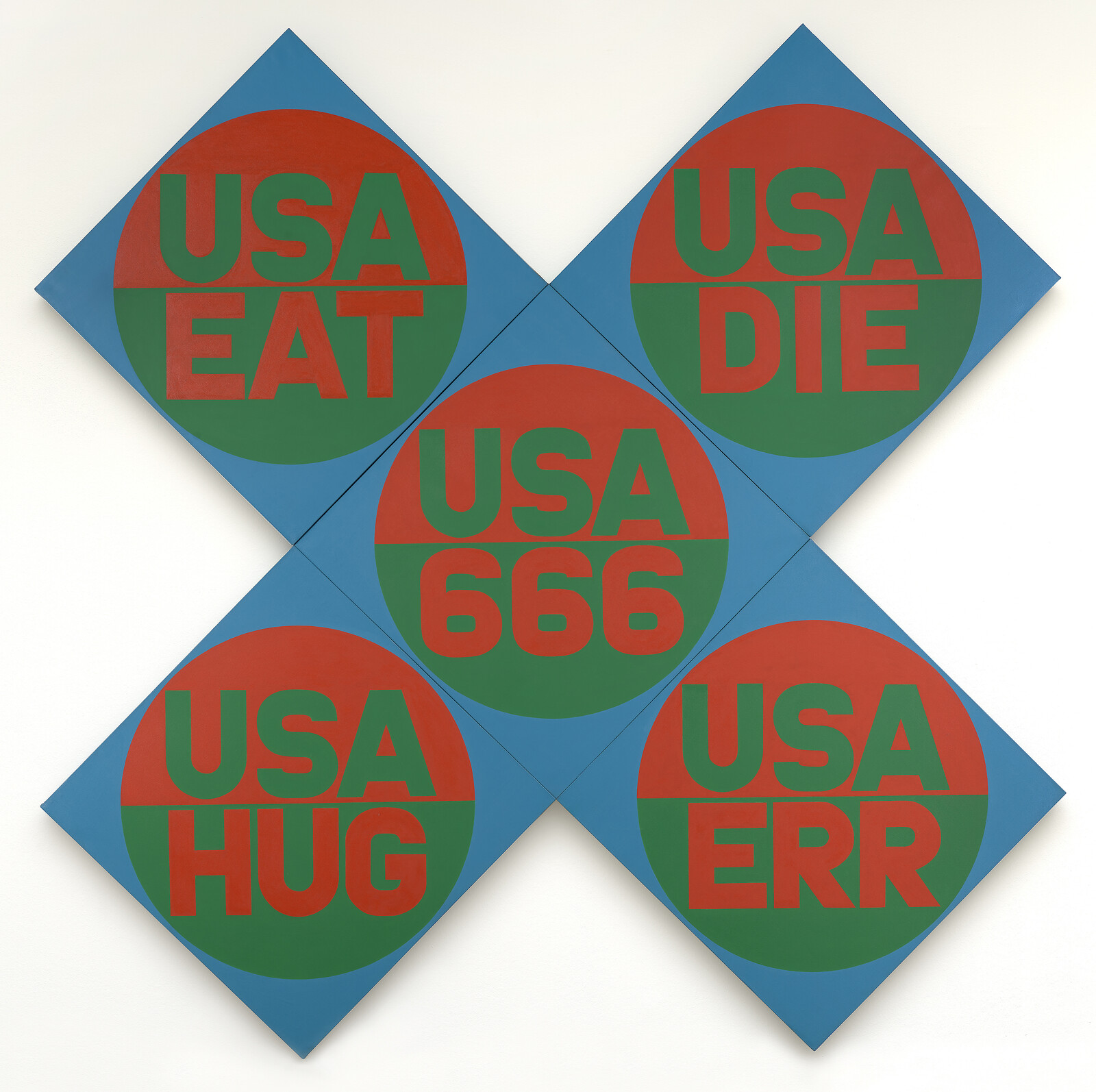

The idea is simple: by placing artworks from rival nations adhering to two putatively opposed ideological systems in “dialogue” (that is, in spatial proximity) we can detect commonalities between and reversals of received wisdom about the systems themselves. The juxtapositions are organized according to sub-themes such as War (where the machine gun in Roy Lichtenstein’s Takka Takka, 1962, is in dialogue with the corpses in Boris Nemenskiy’s On The Nameless Height, 1961), Iconography (where the traffic signs in Robert Indiana’s USA 666, 1971, are in dialogue with the Soviet crest in Erik Bulatov’s Sunrise or Sunset, 1989), Leisure (where Natalya Nesterova’s Singers, 1969, are in dialogue with Ralph Going’s Airstream, 1970), Space Flight (where Lowell Nesbitt’s Splash Down, 1969, and Lift-Off, 1970, are in dialogue with Jury Korolyov’s Cosmonauts, 1982), and so on.

“The Cool and the Cold” must contend, however, with a few simple facts: the US exists, whereas the USSR no longer does; the exhibition’s existence is underwritten by a partnership between the institutions of the museum, capital, and the state; and its presumed viewer is still one, like myself, whose gaze has been socialized by Western rather than Soviet aesthetic norms. On a few occasions, the studied neutrality implied by the word “dialogue” tips its hand in favor of the US. First of all, in the name of the exhibition itself: if Cool is taken to refer only to the paintings from the US, Cold refers to the geopolitical situation in which both American and Soviet artists found themselves. The opposition is therefore merely apparent, and in this imbalance one hears sotto voce the one that is really meant: the cool and the kitsch. Just so, the acknowledgement that the US state also used art to engage in propaganda seems to place it on an equal footing with the USSR, but the exhibition catalogue’s identification of “freedom” as the content of that propaganda is misleading, as we will soon see.

Progressing through the exhibition, I recalled the famous 1978 essay “The Power of the Powerless,” by the dissident playwright Vaclav Havel. Havel considers the life of a greengrocer living under communism in Czechoslovakia, who hangs a sign that reads, “Workers of the world, unite!” in his shop window. The greengrocer, Havel writes, almost certainly does not literally believe the words on the sign, and may not even support the party whose slogan it is, but a series of soft coercions—the fear of losing his job, social pressure, ideology, personal convenience—forces him to hang the sign anyway. In this way, the “post-totalitarian system” disciplines its subjects into living a double life: taking ideology for reality because it seems inescapable, becoming a player in a game they’d rather not play, and, most of all, becoming accustomed to saying the opposite of what they mean. It is not the content of the official propaganda, which no one believes anyway, through which the system secures obedience; it does so by training people to go about their daily business “living within a lie.” This double life was not specific to the Eastern Bloc, however. The United States developed a version of it during the Cold War, which is still alive and well today. Its name is irony. And irony, not freedom, as the official propaganda would have you believe, is the essence of cool.

Consider Nalbandyan’s Lenin. Two-time winner of the Stalin Prize, member of the USSR Academy of Arts, People’s Artist of the Soviet Union, Hero of Socialist Labor, Nalbandyan was as much of a system artist as one can imagine, and the officially sanctioned subject of his 1980–82 painting, the aggressively outmoded style in which it was executed, and the normative, domestic, even bourgeois mise-en-scène all reflect this status. Western viewers will have no problem identifying it as kitsch. Yet insofar as the point of the exhibit’s “critical juxtaposition” is to demonstrate that Warhol’s Single Elvis is also kitsch, it does not go far enough. Everyone knows that Single Elvis is kitsch. Warhol’s genius was to play two notionally antagonistic sectors of the American culture industry—mass-produced popular culture and sanctioned high culture—off one another to show how every time an image changes context, more value can be extracted from it.

What makes this possible, in turn, is the cool, ironic gaze that allows us to be privately committed to the idea that kitsch is negative, while behaving otherwise, because what we are ultimately being asked to admire is not this or that image, but rather the ideological principle truly at the heart of the American system: not freedom, but commodification. In terms of system recognition, Warhol was no slouch: he is the American artist most frequently represented on the list of most expensive paintings ever sold, a far more patriotic distinction than, say, the Presidential Medal of Freedom. What does his Elvis say with a wink to Nalbandyan’s Lenin when the two are placed in “dialogue” at the Gropius Bau? The same thing as Havel’s greengrocer: “Workers of the world, unite!”