How do personal memories become fragments of a political narrative? How can images guide us back through the past? A double-exposed print-out of private and political histories, Aykan Safoğlu’s installation Revolving Dreams (Athens/Istanbul, May 4-7, 2006) (all works 2020) features a series of images suspended from invisible threads. Pages from the artist’s old passport, superimposed with photographs from his personal archive, are enlarged and printed on two long scrolls which hang from the ceiling like waves. The work takes its cue from the bus journey Safoğlu (who was born in Turkey and now lives in Berlin) made from Istanbul to Athens in 2006, along with two friends and a group of alter-globalization activists, to participate in the fourth European Social Forum. The event—which marked the artist’s first encounter with discussions around immigration and climate crisis—brought together activists, NGOs, refugees, and environmental and anti-racist movements. Safoğlu revisits photographs taken over those few days in order to contemplate what the participants would transmit to a contemporary audience, for whom these issues have only gained in urgency.

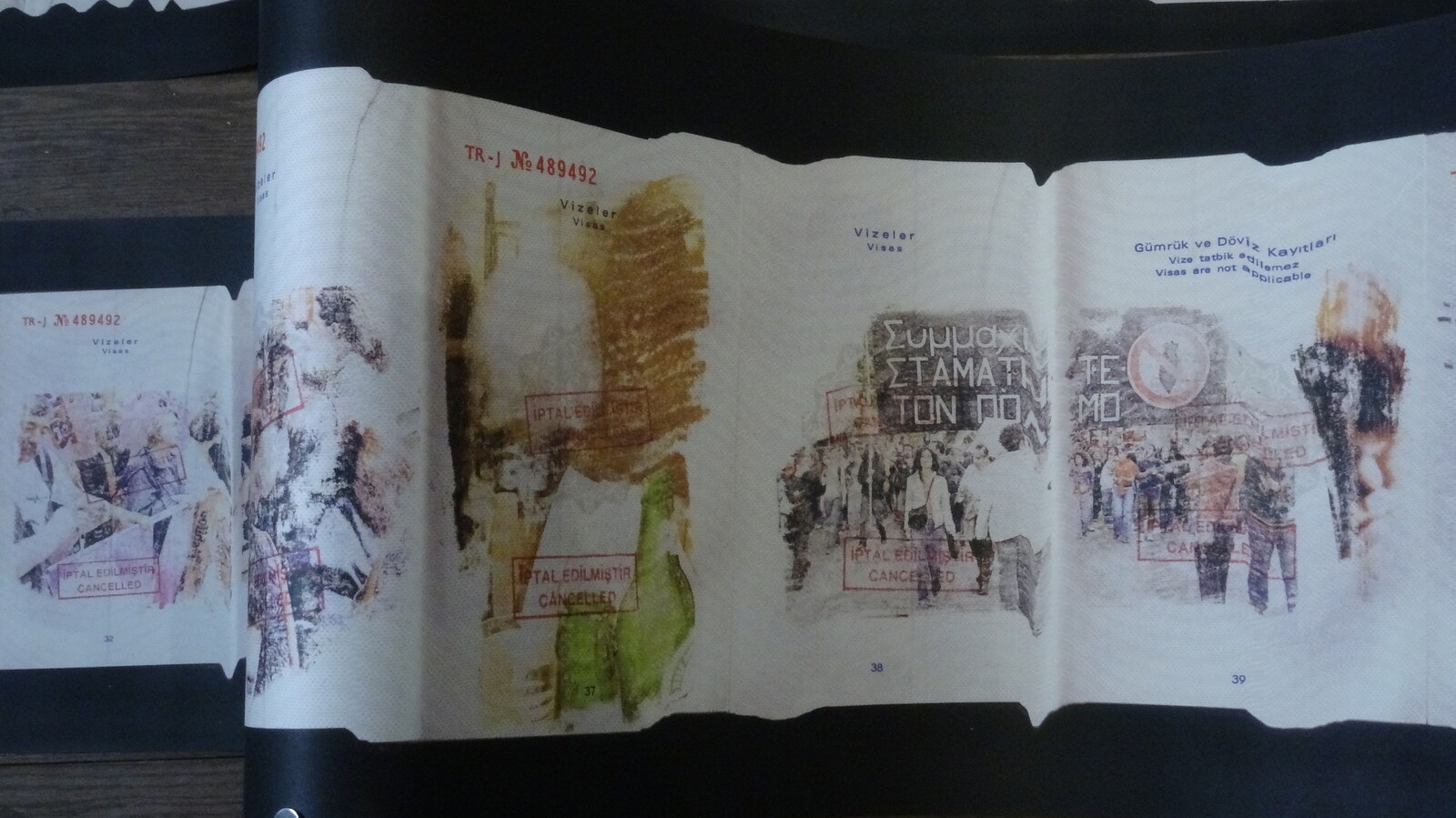

The work invites us to consider the political shifts in both Turkey and Greece since 2006: the Justice and Development Party (AKP) had only recently come to power, Turkey was beginning negotiations towards membership of the EU, and hopes remained that Erdoğan would govern in a democratic manner and bring economic stability. Today, of course, these dreams have failed to come to pass, while Greece has been devastated by an economic collapse which put its own EU membership at risk. Safoğlu’s installation comprises photographs from demonstrations in Athens, as well as images of the Parthenon, the Olympic logo (the games, which took place in 2004, are widely considered to have contributed to the country’s subsequent debt crisis), a police shield, and sleeping activists on the bus. Observing the two long rows of prints, I’m reminded of images on a roll of film. The blurred images, evocative of hazy memory, are juxtaposed with the bureaucratic blue-and-red ink on the passport pages, featuring stamps of all sorts, and the bright visas that require so much effort to get because Turkey is not a member of the EU. There is nothing unreal about a blue passport or a demonstration controlled by the police, but the prints float in the air as if carrying images from a dream.

The installation also features a sound piece titled L-I-n-t-e-r-n-a-t-i-o-n-a-l-e, which is a five-minute-long, slowed-down, lullaby-like version of the communist anthem broadcast from a music box, evoking a sense of childlike enthusiasm which renders communism a sweet, unrealized dream. Safoğlu’s intertwined presentation invites the audience to rethink the crossovers of personal and political histories: romantic nostalgia for the pure enthusiasm of youth is tempered by the realities—mundane or painful—of political struggle. The work explores the problematic relationship between patriotic sentiment and nationalist politics, and the historically complex relations between Turkey and Greece. As Safoğlu writes in the exhibition text, his urge to return to these images from 2006 was initiated by a recent escalation of tensions between the two countries over the ownership of gas reserves in the Eastern Mediterranean. The host institution, Kıraathane: Istanbul Literature House—a non-profit space which opened in 2018—takes inspiration from kıraathanes, Ottoman coffeehouses designed for reading and recitation, where people from different cultural backgrounds came together to discuss politics; they were regularly closed down as potential sites of sedition. Safoğlu’s work draws on the coffeehouse tradition, providing a space where inflammatory topics can be peacefully presented and reconsidered—a rare case in Turkey, where freedom of expression has been undermined over the past fourteen years.

“Revolving Dreams” marks the second in a series of exhibitions at Kıraathane under the title “How happy is the one who says I’m an equal”—a play on the motto of the Turkish Republic, “How happy is the one who says I’m a Turk”—which aims to create a platform to discuss nationalism in relation to Turkey’s political history. The first exhibition, “Not Approved,” featured works by Kurdish artist Zehra Doğan, produced in prison with the daily materials to which she had access, and smuggled out of her cell as dirty laundry. The program will end with a group exhibition, curated by Ahmet Ergenç, titled “Sensitive Intervention,” which sets out to imagine alternatives to the nationalist ideology that has shaped Turkey’s past. It’s a project that resonates with the present show, where Aykan Safoğlu takes us on a journey both in time and space, at a moment when most of us are in confinement and our passports dysfunctional.