It’s summer in May. It’s been a long winter, and a long semester teaching art history is drawing to a close. The past four months I’ve been talking to my students about the political possibilities of art: trying to convince them not to look away, but to be moved, to pay attention, and to think of that participation as a form of political agency. We’ve talked about how to look at historical work with an eye to 2018. “Is this still useful?” I ask them of 1950s painting, or video work from last year. My students don’t always have an answer. Nor do I. But I keep asking and looking, knowing that, while I may not always find answers, paying attention is important.

At Sfeir-Semler Gallery (Beirut/Hamburg) are drawings from Rabih Mroué’s Leap Year’s Diary (2006–16). Small framed works are composed of clippings from mostly Lebanese newspapers, cut out and glued onto paper. There are objects (a bell, a truck, a military plane flying across a blank white-paper sky) and full scenes (a boy reaching for a string tied to a bird’s foot); there are shells of homes, and figures standing alone, looking at what may have been landscapes before they were cut out of them. Leap Year’s Diary comprises 366 small works on paper, a selection of which hangs in this booth in an arrangement that allows for empty spaces. Some reach so high up the temporary wall that it’s impossible to observe them without a ladder. Like the out-of-context newspaper cutouts, the display reflects how hard it is to ever see the full picture.

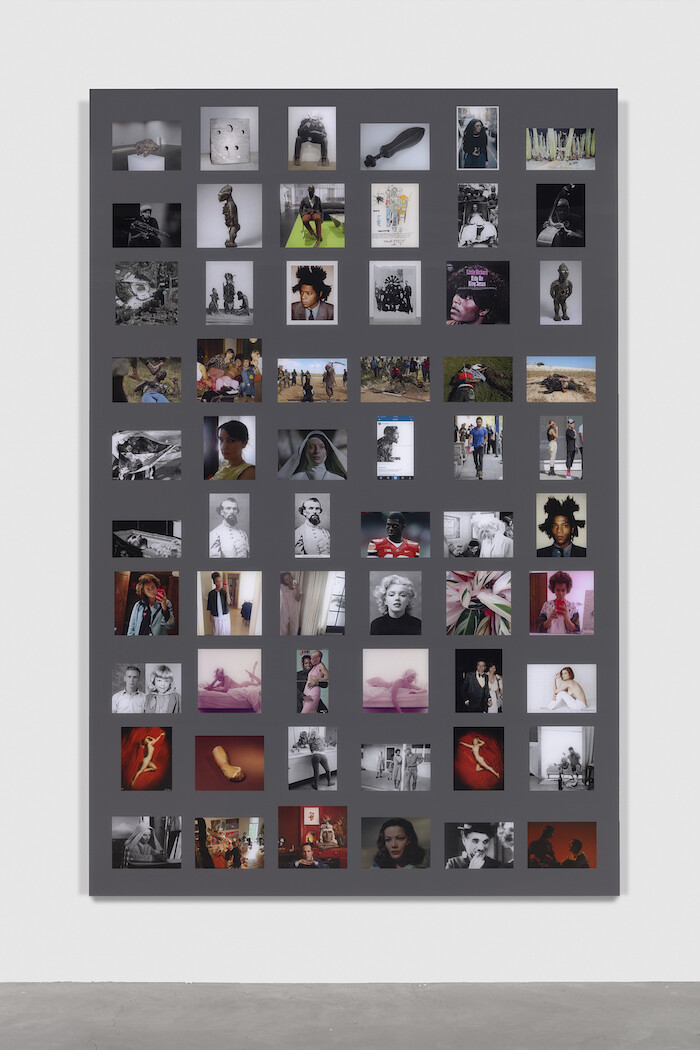

Another collection of arranged, found, and transformed images is found in filmmaker and artist Arthur Jafa’s solo presentation at New York’s Gavin Brown’s Enterprise. Jafa, who for years has been assembling images of black culture in binders, in which montages are created from the conflation of pictures and from the movement across pages, here presents similar image research, but expanded across six massive tableaus. Jafa arranges found images in rows of six, prints them, and attaches them to aluminum panels. Here are Marilyn Monroe and Jean-Michel Basquiat; there are athletes and musicians and Instagram posts and selfies, family photos, an image of a worn copy of Henry David Thoreau’s Walden (1854). Like the images collected in binders, the connections between the different figures feel intuitive—it’s up to the viewer to complete the picture. But unlike the binders—which are shown on tables, requiring participation in the turning of pages, which generates intimacy—these large pictures are impressive on the scale of history painting.

Mroué was trained in theater, Jafa in cinema. It’s hard not to think an art fair as a stage set, complete with temporary walls and delineations of space. New York’s Essex Street gallery stands out for staging a coherent installation in its booth. On one wall is a new work by Cameron Rowland, Assessment (2018). A grandfather clock, taken from a plantation in South Carolina, stands beside framed mid-nineteenth-century tax receipts from Mississippi and Virginia, which collected property taxes on slaves—governments whose tax funds are tarnished by their history to this day. Assessment is presented alongside Ghislaine Leung’s installation 58 : 96 / 49 (2018), which includes a children’s playhouse, with red walls, a gray roof, and a white door. Affixed to the booth wall is a strip of aluminum tape, marking the minimum ceiling height specified by the building codes of the country in which the work is exhibited. The playhouse, a reminder of the white picket fence dream, is unnerving next to the loaded household symbol of the grandfather clock (“plantation owners,” the label reads, “adopted clock time during the late 18th and early 19th century, further regulating the labor of slaves”), and below the claustrophobic confines of the ceiling Leung’s tape hints at. The clock works. It’s hard to hear it above the noise and activity of a fair, but its ominous ticking continues, like an unfinished story.

The passage of time is the subject of a solo presentation by Chen Zhe, at Shanghai gallery Bank. Although these are much less political works than I was hoping to find at Frieze, it captured me in its indirect, meandering exploration of a transient subject: dusk. This coherent selection is taken from a larger, ongoing project, called In Towards Evenings: Six Chapters (2012–ongoing), in which Chen explores dusk as a link between language and visual representation. Refusing the more immediate associations of pink and red hues, the works in the booth are all black, white, and gold. There is a light-filled clock on the wall; a terrazzo sculpture inlaid with the words “hope” and “fear,” which shimmer as light reflects off pieces of brass set into the material; and an old medicine book, from which Chen has eliminated words, reducing the language into beautiful, sneaking experiences of sunset: “sighing/ singing/ alternating with vexation/ hilarious, joyously.”

At Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, stands Hank Willis Thomas’s Larger than Life (2018), a stainless steel bust (though the face, cut off just above the nose, isn’t recognizable—this isn’t a portrait). Set on a taller-than-lifesize pedestal, each hand of its outstretched arms grips a basketball. The basketballs are less polished than the figure, the mirror-like surface of which gives warped reflections of the artworks in the opposite booth. Thomas has referred to athletes in previous works, such as I am the Greatest (2012), which references the titular boast by Mohammad Ali. In Larger than Life, it’s not celebrity but scale that draws your eye, as you look up at the sculpture that expands into the space.

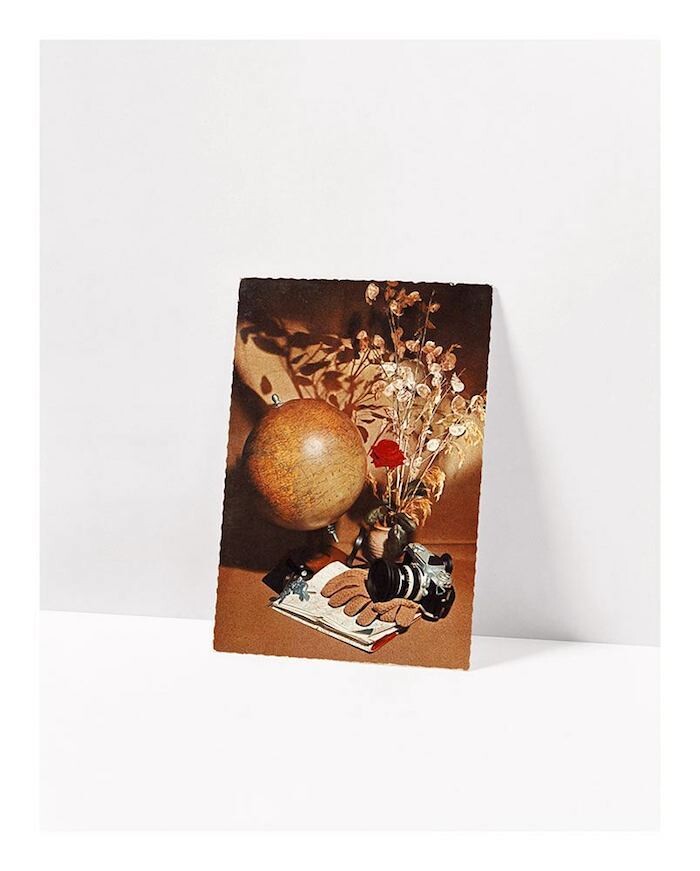

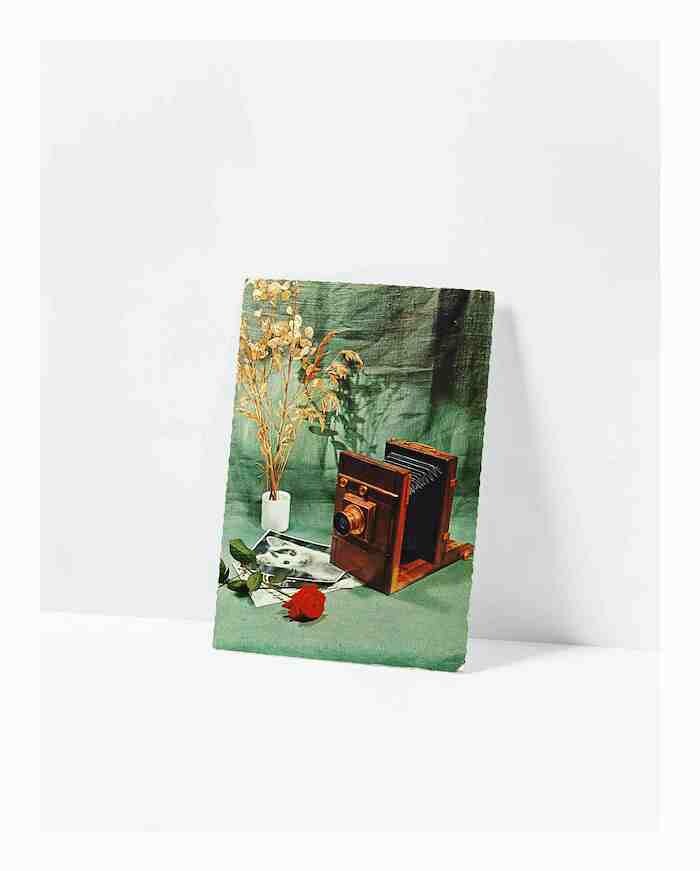

Less heroic references to art history can be found elsewhere. At São Paulo’s Mendes Wood DM, a floor work by Adriano Costa, Prèt-A-Porter (2016), features a chessboard-like grid of steel and copper squares swathed in shrink wrap. It’s a wink at Carl Andre or Arte Povera: a contemporary rendition, packed up and ready to go. At Anton Kern, New York, are two photographs by Anne Collier, Italian Still Life #2 and #3 (Postcard) (2012). Both are photographs of photographs—old postcards pictured leaning against a white wall. Like many of Collier’s works, these postcards feature old cameras, and have a nostalgic tint to them. These forgotten objects once meant something, however fleetingly, and become like Vanitas paintings when she shines a light on them.

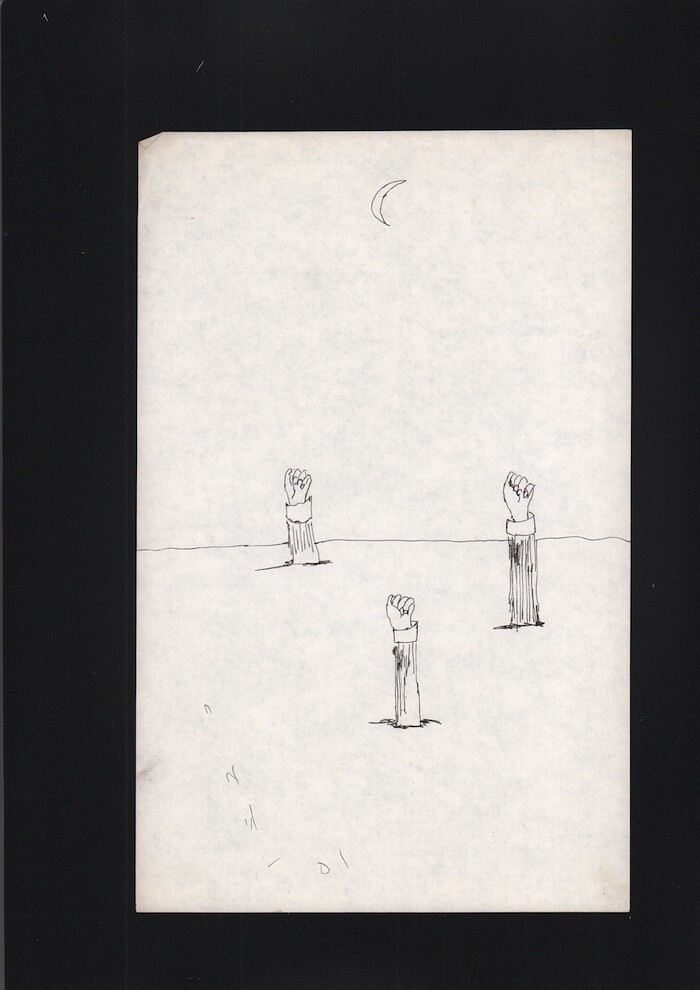

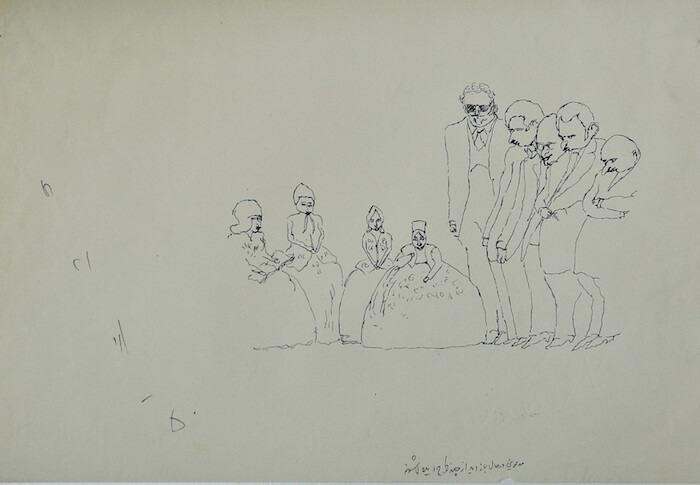

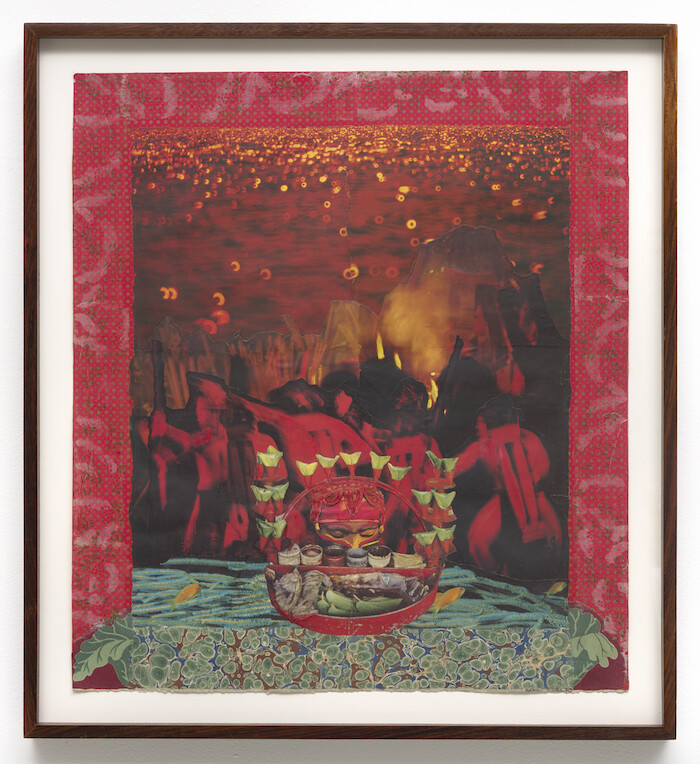

In the Spotlight section, which is dedicated to solo presentations of twentieth-century artists, Tehran gallery Dastan dedicates its booth to a solo display of drawings by Ardeshir Mohassess, an Iranian artist and illustrator who lived in New York and died there ten years ago. The drawings included are from two series: “Vaqaye Etefaqie” [Current Events] and “Shenasnameh” [Identity Card]. In both, individual characters and crowd scenes are depicted full of humor and energy. They predate the Iranian Revolution, but it’s hard not to read them in its context: hands rising, fist closed, from the ground; official-looking men in suits demanding something from smaller, rounded, feminine figures. Closeby in the same section, Roberts Project from Los Angeles present a selection of works by Betye Saar. These pieces exemplify the 91-year-old artist’s choice of materials, which combine high-art and craft: Dervish (1979) is an embroidered mixed-media collage on a red handkerchief; The Domain of Chance (1979) includes fabric, jewelry, and a frame within a frame. At the fair, her works, which bring together questions of race, class, and their links to the related histories of art and folk art, seem more current and contemporary than most of those in the sections dedicated to younger galleries and artists.

On the last day of the fair, the heat wave ends. It is gray and I am waiting for the rain to begin as I get on the boat back into the city and try to catch sight of Adam Pendleton’s outdoor work Black Dada Flag (Black Lives Matter) (2018). A flag reading “BLACK LIVES MATTER,” it will stay on Randall’s Island through November 1, where it will be useful to us as a constant reminder: visible to passing boats, to the kids who play sports in the island’s old stadium, and maybe, on a clear, different day, to the residents of the neighborhood across the river. We’re all still waiting for different days.