April 13–June 5, 2017

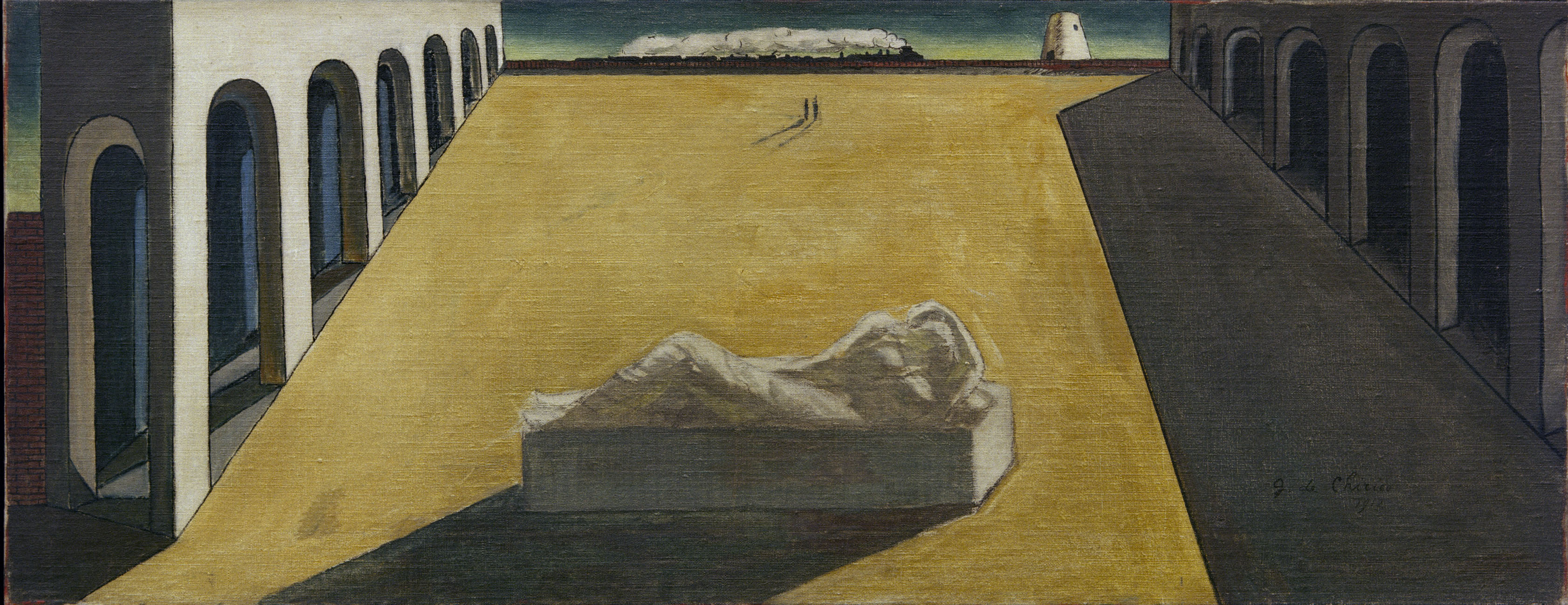

According to the exhibition’s introductory text, “Quiet,” curated by SALTS director and Art Basel Parcours curator Samuel Leuenberger, is inspired by Susan Cain’s 2012 book of the same title, which champions introverts in a world skewed in favor of the ebullient extrovert. It is an odd premise for an exhibition, given that artworks are generally left to speak for themselves and their mediation is delegated from the artist to the curator or the gallerist. Yet now that connections and networks are so strategically fostered, have we lost faith in art’s own inherent power? If the art world is utterly deaf to the potential of a silent or slight gesture, we are doomed. What this show achieves, however, is an exploration of different kinds of quietness and distance between artist, media, and artwork. At its center, a city lies in a crescent at our feet. It is a ruined city, abandoned, the bones of buildings, highways, and civil engineering bared, dirt and sand gathering around it. Houses are missing roofs and sides, though a few bare lightbulbs still burn brightly. Youssef Limoud’s Geometry of the Passing (2017) is made from found detritus, brownish torn waste materials and lost objects such as pots, chopping blocks, urns, a chemistry flask, and a metal basket. The miniature metropolis clusters and stretches below viewers as if it had developed organically, though monumental sections also suggest a builder’s former hubris.

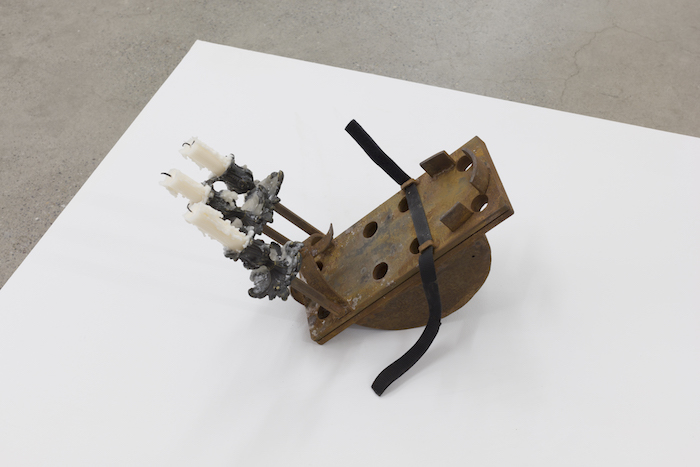

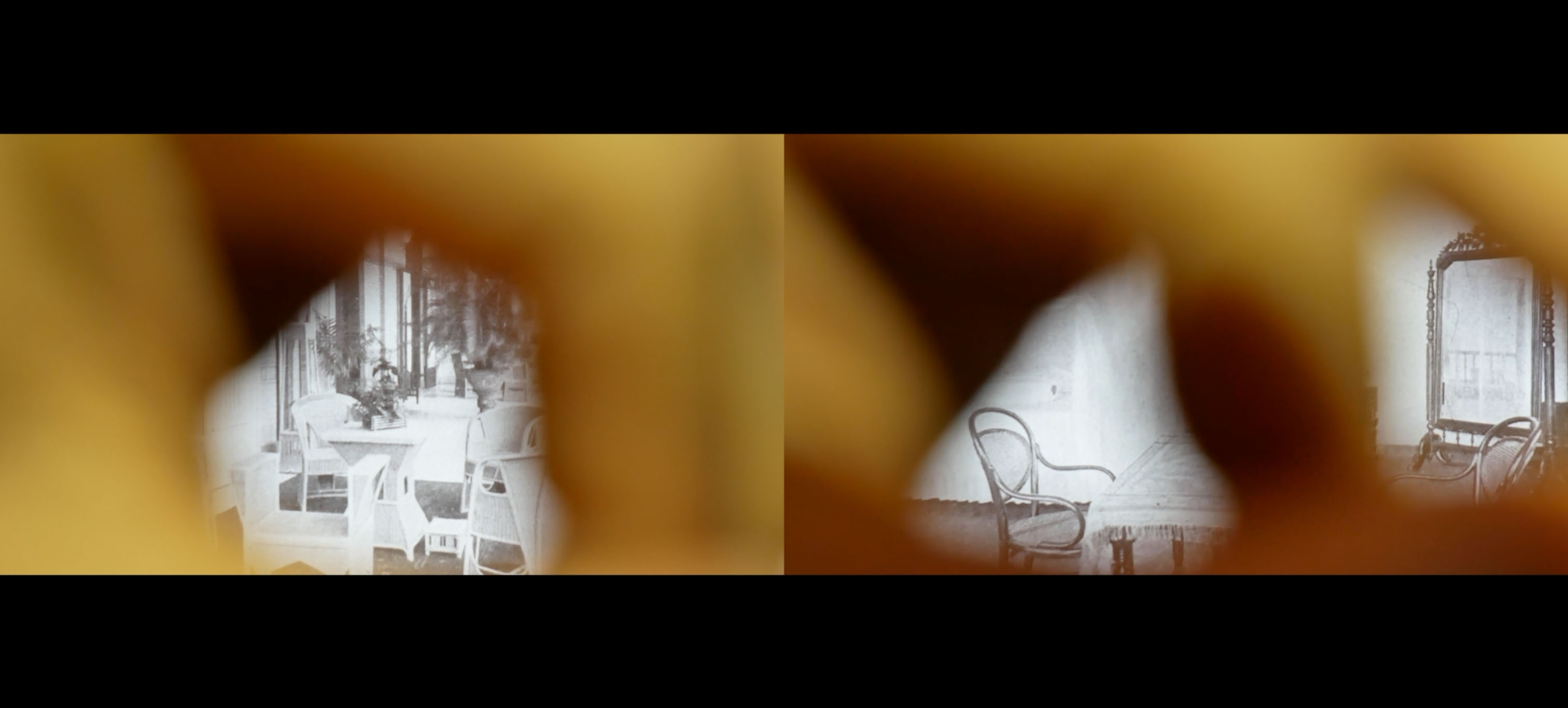

Like Limoud’s, Mohammad Ghazali’s works could be characterized by their “poor,” unpromising materials and modest approach. Ghazali’s small black-and-white photographs from the artist’s 2016 “Dredge” series, propped around the walls of the gallery, focus on details of a real city, his native Tehran. Visitors can pick up the metal frames and examine pictorial elements that Ghazali zooms in on using layers of masking tape that frame them in increasingly close crops. Ambition is writ small: in one photo, The model of an airplane in Rome alley (2016), the titular model appears to soar above a concrete block building; in others a tree is the subject, or a cloud. The tight frame culls all but the punctum, a subdued finale to the drama of the picture, even deliberately unshowy. In a contrasting application of found media, Augustas Serapinas has taken metal pieces from art-school scrap and remade them into exercise equipment, here showing the slightly menacing Ripper (2016). When activated, as it is at least weekly by someone stepping into it and tying it around their foot, lit candles threaten to burn the user if their balance fails.

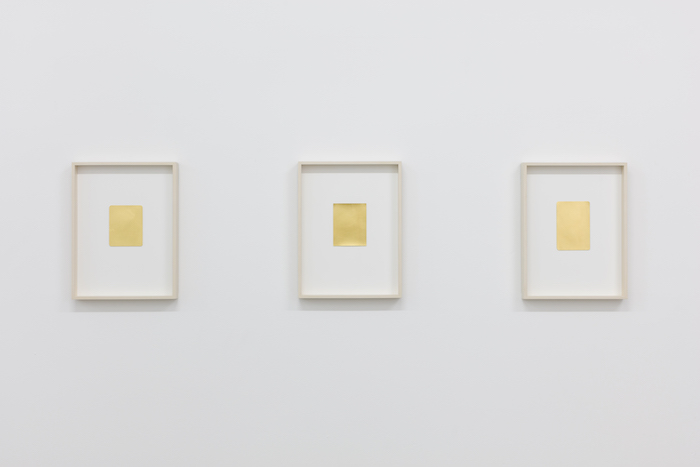

Christina Forrer’s two largely uncolored tapestry portraits, both untitled and from 2016, employ the medium in a deliberately naïve, expressive manner rarely seen in a contemporary art context; one shows a garlanded bride and the other is a head inspired by Hans Holbein the Younger’s The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb (1521), drawing just Christ’s head with its sunken, slack jaw as a mirror image. While Forrer’s pieces bring things to our attention in an unassuming fashion, other works deliberately repel the viewer. Stéphanie Saadé’s “Golden Memories” (2015-7) are photographs of her childhood that she has muted by covering them with a layer of gold leaf. Seductive surfaces now obscure images left only in the artist’s memory. Haris Epaminonda’s Untitled #11 a/y (2016) literally turns away—the precise installation of sculptural and painted elements centers on a plaster replica of a classical sculptural head that faces the wall.

Encountering an ascetic approach is frustrating when you’re accustomed to being drip-fed. These works don’t clamor or shout; they exist in stubborn, quiet isolation. It’s provoking if you want art to be loudly angry, to resist, protest, or to be engaged in the issues that concern you. On the other hand, a momentary pause choreographed like this one enables you to disentangle artist and artwork, and helps resist knee-jerk instrumentalization. These works are allowed the time, space, and silence in which to assume their own agency. Limoud’s city makes us marvel at the very idea of architecture while equally reminding us of our destructive potential; Ghazali’s Tehran is framed by its residents, not its designers. Thanks to Forrer’s remaking, Holbein’s Christ yawls still, some 500 years later. There is a gap between an artist and the effect of their work; take the exhibition title as an imperative—be quiet!—and we can begin to hear the works’ own voices.