What does it mean to engage the architectural worlds of cinema at a moment when cinema no longer dominates the experience of moving images, when celluloid film has been displaced by digital video, and when atomized online streaming has largely eclipsed the collective reception of movies on the big screen? Cinema long served as the privileged reference point for conceptualizing themes of movement, flow, and time in architectural theory.1 Today, however, it is but one cultural form among a proliferating array of platforms through which moving images circulate. Where Hollywood cinema was once decried as emblematic of a totalizing culture of spectacle, today the ever-changing currents of social media and gaming arguably exert a greater power over visual culture and its politics.2 The questions asked of architecture in movies used to hinge on interpreting the similarities and differences defining film and architecture as distinct media.3 As it becomes increasingly unworkable to define the relation between architecture and cinema in terms of medium specificity alone, we might instead look more closely at how these fields of cultural production have intersected with broader histories of screen media and their operations.

Screens are at once optical devices, central to the exhibition, reproduction, and circulation of moving images, and environmental and spatial technologies with varied and complex histories. For this reason, screens should be recognized as something more than surfaces that make something visible. They are technologies essential to producing a wide range of effects, from projection, substitution, and camouflage to concealment, partitioning, and sorting. To recognize screens as technologies, we should not imagine screens as objects, but as dispositifs where a range of techniques are enacted. As sites where processes of copying, combination, alteration, filtering, and projection are enacted, screening cannot be confined to a particular medium. Indeed, long before they were optical devices, screens were agents of environmental operations, operations that are today reasserting themselves across a range of cultural domains.4 Rather than define or redefine the relations between cinema and architecture as distinct mediums, the current moment of dissolution provides an opportunity to revisit and retheorize some of the technical grounds that architectural and cinematic practices have shared.

From View to Setting

“If we notice the location, then we are not really watching the movie. It’s what’s up front that counts.” These lines, from Thom Andersen’s celebrated 2004 video essay Los Angeles Plays Itself, point to a paradox for anyone interested in the architecture of cinema. Buildings, streets, and sets reach a far vaster audience through the movies than they do in the locations where they physically stand. Yet seldom is the built environment the center of cinematic attention; even less does it receive active examination. Pay too much attention to the buildings and you lose the plot. Follow the story closely and the locations become little more than fleeting features of a scene’s ambiance. If one follows Andersen’s logic, engaging with film architecture means not really watching the movie. But, perhaps, it simply means cultivating other habits of looking.

The pressure to concentrate attention upon the foreground has not always been a constant characteristic of cinema. When mass audiences began to encounter cinematographic projections on makeshift screens in cafés, converted storefronts, or fairgrounds at the end of the nineteenth century, they confronted not only images that seemed to move, but views of specific places. Streets, buildings, monuments, parks, factories, and train stations were among cinema’s first subjects. Within a year of the cinematograph’s first public presentations in 1895, camera operators were dispatched across the planet to shoot brief single-reel films. In these early movies, cities and buildings were not backgrounds; urban milieus, whether familiar or exotic, were the attraction. It was only after the turn of the century, when filmmakers began producing more films with fictional plots, that shooting moved increasingly onto stage sets. As actors and plots assumed greater importance, fictional settings and shooting locations were increasingly separated. Correspondingly, a new distinction between foreground and background was articulated through screening techniques that manipulated different zones within the shot.5 Techniques for physically screening off parts of what appeared before the camera—known as matte shots—soon emerged to generate special effects from the non-coincidence between foreground and background. Mattes allowed parts of the film to be obscured and later re-exposed, making footage filmed at different times or places appear as part of the same scene. Matte shots thus produced a type of screening internal to the filmed image, underscoring how screening techniques are both internal to and distinct from the materiality of the projection screen as a surface of appearance.

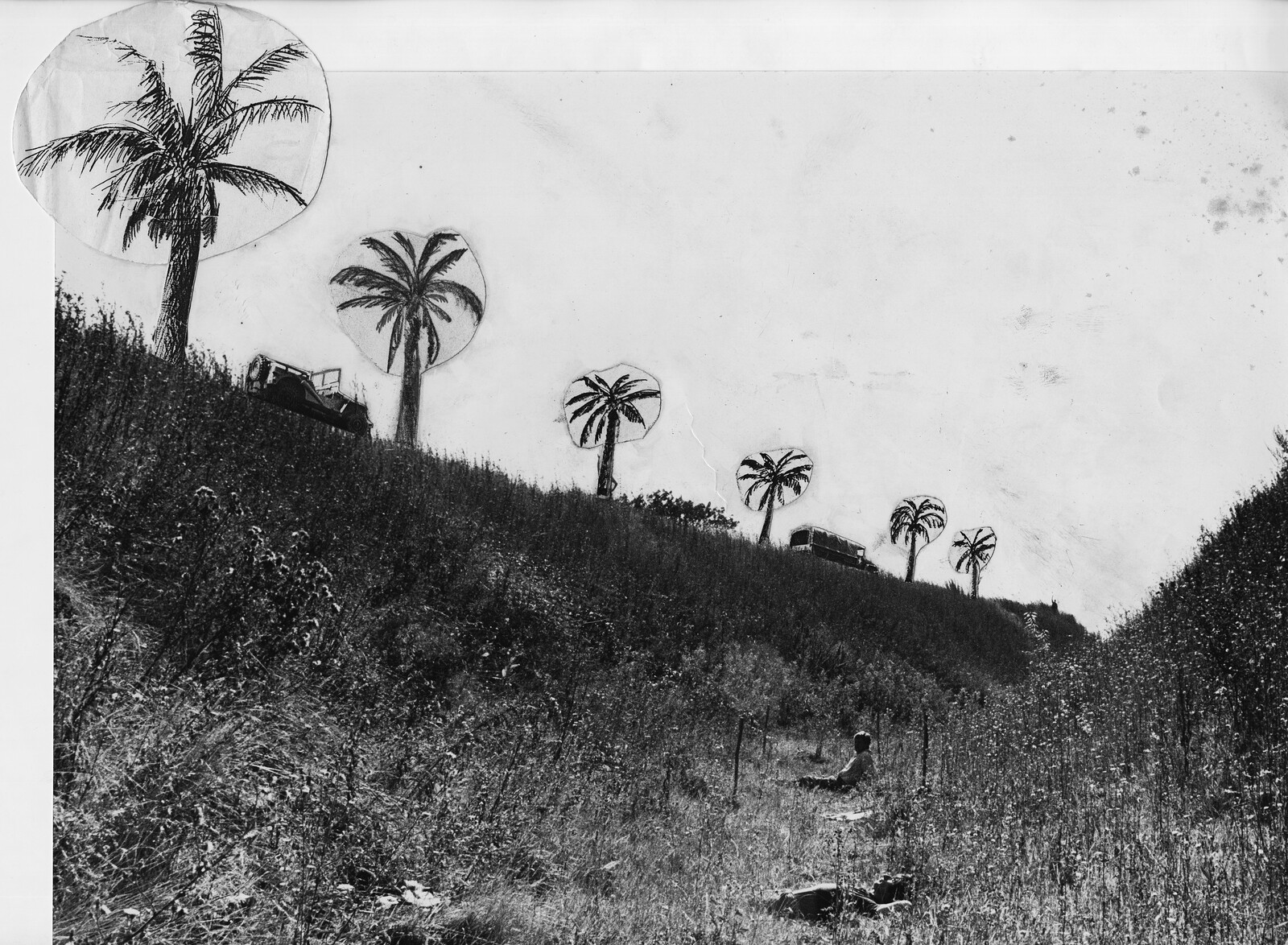

Screening techniques circulated at the intersection of a range of architectural, journalistic, photographic, entertainment, and filmic practices. Norman Dawn, the pioneering filmmaker who helped introduce matte painting to Hollywood, first learned basic techniques of photographic manipulation when assigned to photograph buildings as an employee of the Thorpe Engraving Company.6 Tasked with removing objects such as light posts from the foregrounds of new buildings, Dawn avoided the laborious work of retouching his photographs and instead transformed them by placing a sheet of glass with a painted tree in front of the camera’s lens in order to obscure and transform the offending elements. Taken up within cinema, such techniques were used to create opposite effects. The filmmaker and magician Georges Méliès exploited the humorous potential of matte techniques in The Man with the Rubber Head (1901), in which a double exposure combining two separately filmed sequences generated the illusion that Méliès was inflating and deflating his own dismayed head until it finally explodes. The following year, Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery (1903) used a matte technique to integrate two pieces of footage from distinct locations: a view of a moving train was made to appear within the window of a telegraph office mocked up on a film stage. Where Méliès manipulated the discontinuity of background and foreground for comic effect, Porter aimed to subtly fuse different shots, producing an illusion that “located” a staged interior along a railway line.

It was during these same years that architects began to insert drawings into photographic backgrounds for publicity purposes.7 These hybrid media documents have typically been understood as part of the history of photomontage, yet they should also be recognized as part of a broader genealogy of techniques for manipulating relations between foreground and background. The drawings that architects inserted into photographs in the years before World War I often aimed to make fundamental transformations in a scene while preserving photographic verisimilitude. And indeed, these combinations often attained a high degree of seamlessness. If such images have been hailed for creating an illusion of continuity between disparate elements, they also point to the power that photographic backgrounds were coming to assume in architectural visualization. Whether developed for competitions or for promotional purposes, the background is neither a neutral datum nor an arbitrary surround. It serves as the frame of reference for comprehending the building, as well as the technical ground in which drawing now operated. Not only were drawings developed on the basis of a site photograph’s underlying perspective, but the grain of photomechanical texture increasingly defined the facture of a building’s appearance.

In the 1920s, architects like Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and El Lissitzky took up this format with a new awareness of Dada and Constructivist photomontage. And while they remained within traditions of perspectival realism, their images pushed this convention to its limits. Drawings for projects that exceeded the bounds of then-current construction practice were made to appear in familiar locations, underscoring the emphatic difference between projected buildings and existing urban contexts.8 By the 1930s, photomontage was becoming more routine, a format increasingly deployed for architectural competitions, in exhibitions and magazines, and even as a stock technique found in advertisements, on billboards, and in newspapers.9 This process of banalization was not one of unidirectional flattening, however, but of dialectical transformation. Techniques subject to routine repetition were seized at a later moment to produce effects of estrangement.

By the 1960s, an emerging generation of architects around the world mobilized photomontage to produce second-order effects of defamiliarization.10 These projects did not emerge from a common movement, shared milieu, or political ideology, yet they testify to the ways in which manipulating relations between foreground and background served a critical purpose at a moment when international-style architecture was increasingly criticized for homogenizing urban landscapes around the globe. Consider, for instance, Arata Isozaki’s 1962 Future City (Incubation Process), in which the architect cut up his own drawings for a suspended urban megastructure in Tokyo and glued them into a radically different background: a photograph of the remnants of a Doric temple. Fusing an experimental vision for future vertical growth in the megacity with classical remains, Isozaki’s altered background cautioned that such visions of the future may be destined to become ruins themselves. Hans Hollein’s Highrise Building, Sparkplug (1964), removed a generic engine component from period advertising and placed it in rolling Austrian farmland. The plug’s ribbed profile takes on the guise of a surreal tower dwarfing the surrounding houses, dramatizing a clash between technological form and pastoral traditions. And in 1970, Jorge Rigamonti inserted an anonymous piece of industrial equipment into a photograph of Caracas, suturing it to a network of oil pipelines. It is the background that endows this unprepossessing technical object with seemingly enormous scale and power, making it into a symbol for the outsized role of petroleum exports in Venezuela’s modernization programs.

Among the best remembered of this genre was Superstudio’s Continuous Monument project (1969–1972), a sprawling series of photomontages that narrated the rise of a building designed at a planetary scale; a linear city expanding beyond the wildest dreams of modernist planners. Each of the images, which were designed to function as stills within a film, inserted a consistently generic volume into a photomechanical background by meticulously matching the drawing to the underlying image’s perspectival schema.11 The project’s nearly thirty scenes appropriated backgrounds from glossy lifestyle magazines, period advertisements, postcards, or travel posters. Cinematic technique was key to envisioning this architecture; its planetary scale cannot be encapsulated in a single image but only via a consistent set of photomontages perceived in sequence. Techniques of montage both within and between images transformed what might have appeared as an arbitrary accumulation of promotional vistas into a “continuous” planetary building, a vast edifice that the accompanying script described as a world “rendered uniform by technology, by culture, and by all the inevitable imperialisms.”12

Not long after, Rem Koolhaas, Elia Zenghelis, Madelon Vriesendorp, and Zoe Zenghelis took the photomontage format and cinematic narrative of Superstudio’s Continuous Monument as a point of departure for their early landmark project Exodus, or the Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture (1972). The project’s establishing shot inserted a gridded linear city into an aerial photograph of London’s West End. Once again, it was the collision of gridded blankness with a dense photographic ground that was developed into an elaborate scenario, one in which the experiences of an abstract, generic, and confining city proved more pleasurable and seductive than the existing, historic metropolis.

Dislocating an object from its background or introducing an incongruous object into an unexpected context underscores how the relationship between figure and ground, or building and site, can be as dynamic as it is potentially arbitrary. Montage has often been theorized as a symbolic form for urban modernity, yet these image sequences invite us to see something else: as a screening technique, montage was a means for exploring and exploiting the instability of photomechanical grounds. Such grounds are not strictly a question of physical substrates, such as printed paper or celluloid film. Rather, the grounds constructed and destabilized in these images point to the broader cascade of techniques for appropriating, producing, and circulating images, which include processes of collecting, filing, copying, drawing, cutting, layering, gluing, and captioning. Such material operations are not only a particular skill or manner of doing. Understood as cultural techniques, they should be recognized as the base operations out of which symbolic distinctions are enunciated.13 As such, they underscore the degree to which photomechanical procedures formed the conditions in which architectural conception operated by mid-century.

If these media techniques determine the situation in which communication takes place, they do not necessarily determine what gets thought. What they underscore are the ways in which architectural conception emerged through processes that navigated, appropriated, and intervened in the era’s media cultures. What began as a set of techniques for exploiting the surreal effects arising from the dislocation of background and foreground progressively developed into one of the era’s most influential narrative modes: speculative scenarios that served to comment on the present while also projecting urban futures that verged on science fiction. Taken together, they reveal how efforts to shift disciplinary discourse during the long 1960s engaged the growing hegemony of screen-based media, appropriating techniques for image manipulation, adopting conventions drawn from film scripts, and mobilizing optical technologies such as slide projectors and 16mm films.

Environmental Screens

Today, the dislocations of context explored in matte shots and in architectural photomontages might well call to mind a newer generation of techniques for altering and manipulating backgrounds, techniques that are increasingly integrated into moving image software and communication platforms. While the techniques used in early matte processes were often jealously guarded by individual artists or production studios, contemporary descendants of such techniques have followed a path of banalization not unlike that of photomontage. Where once green screen technologies were the province of television studios and film sets, today they occupy the bedrooms of aspiring social media influencers. Analogous operations are commonly integrated into the interfaces of smartphone apps and video telecommunications software. And yet, important differences can be noted within this broad spectrum of techniques for altering relations of foreground to background. Glass matte techniques formerly occupied the space between the lens of the camera and the background of the shot, with each matte being an overlay designed for a particular scene. Green screens, by contrast, are placed behind the actor, and operate via a calibrated contrast between a specific hue of green and human skin tones. Whereas matte screens relied on painterly brushwork, pigment, and perspectival alignment, green screens rely on the automatic detection of color values in digital editing software. Often referred to as chroma keying, software identifies and separates a specific color value and makes that area into an independent layer. Rendered transparent, the layer can then be filled with any digital content whatsoever, making whatever is typically in front of the screen appear in a different setting.

Not unlike the classic movie screen, green screens host an image only through a play of appearance and disappearance; for an image to appear the material surface must withdraw from perception. Yet unlike the movie screen, a green screen does not rely on the action of projected light. With the green screen, disappearance relies on a more dispersed computational interaction that coordinates background, foreground, camera, color values, computing hardware, and animation software. Such screening techniques render backgrounds more arbitrary and fungible, even as they reinforce highly conventional figure/ground separations. Such a dispersed computational interaction extends into physical space. In the most sophisticated urban film production, multiple green screens distributed throughout the scene are used to selectively edit, alter, and coordinate numerous background elements. Green screen technologies can also be connected to augmented reality software to produce real-time interactive effects through the screen of a spectator’s smartphone.14

With the rise of green screen technologies, the manipulation of the foreground/background distinction shifts from cultural techniques for cutting, painting, and projecting toward a set of techniques in which software, from animation programs to augmented reality apps, plays the central coordinating role. More than a surface of display, it is helpful to think of such screens as environmental technologies. On the one hand, the positioning of green screens redefines the relationships between cameras and their surroundings; on the other, a coordinated relationship between different screens in space defines the situation in which actions take place. In this sense, the green screen points to a larger digital assemblage whose effects are visual and spatial yet whose workings cannot be understood in strictly visual terms. As the capacity to combine elements of disparate origin becomes more sophisticated, it also becomes less palpable; its technical reality disappears beneath seamless appearances generated by compositing software. What does the banalization of such screening techniques herald? Will the ability to seamlessly blend and manipulate digital backgrounds, actors, objects, and location shots produce a new generic image of the city, an urban imaginary inhabited collectively but which exists nowhere other than the screens of our laptops, televisions, and smartphones?15

The argument that such screen technologies are creating a generic city recalls Rem Koolhaas’s notion of the same name, a concept whose context deserves some elucidation. Advanced amid debates over the impact of globalization on architecture in the early 1990s, Koolhaas’s manifesto on the generic city responded to concerns that equated globalization with the advent of a new nonspecific spatial condition, one not unlike the photomontages that Superstudio and Koolhaas himself circulated in the early 1970s. In such a vision of globalization, differences rooted in place were subsumed by a homogenization of the urban environment brought about by standardized technologies and cultural forms.16 With the concept of the generic city, Koolhaas turned these concerns on their head, embracing the generic and the homogenous as a potentially liberating release from the straightjackets of ossified historical identity. The generic city, he argued, was not reducible to nondescript, formulaic, and repetitive building. It retained a capacity for invention that was likened to the architecture of cinematic production: “like a Hollywood studio lot, [the generic city] can produce a new identity every Monday morning.”17

If green screen techniques, like Koolhaas’s studio lot, are understood as architectural elements capable of producing new identities, they remain a form of novelty rooted in standardized, automated, and generic protocols.18 Yet unlike traditional studio lots, green screens and their analogous technologies are mobile and dispersed, marking points where the operations of digital production collide with the material and topographical specificities of various locations. If screening techniques provide some insight into the shifting technical grounds that underpin practices of visualization of and in the contemporary city, they demand a stronger conception of how screens simultaneously depend on and transform their environment. As distributed devices, digital screens are no longer fixed in space, solely concentrated in privileged urban centers, or enclosed by specific architectural typologies. Yet at the same time, screens continue to depend on telecommunications infrastructures with specific territorial limits, just as they facilitate the tracking and location of spectators. Screening techniques and know-how are central to the multi-billion-dollar film and television industries, and they are routinely advanced as models for public interactivity within urban design initiatives.

For these reasons, concepts of disjunction provide a sharper critical framework than the generic for conceptualizing the urban effects of screening techniques. The desire to seamlessly integrate figures into shifting backgrounds testifies to a condition defined by dislocation. Countering theories of globalization like Koolhaas’s generic city, Arjun Appadurai famously argued that the movement of cultural forms across borders and continents was a process that also entailed complex disconnections between identities, media systems, technologies, capital, and ideologies.19 During the same years, Bernard Tschumi mobilized the concept of disjunction to theorize the increasingly unstable relations between form, program, and use as conditions of contemporary architectural production, a critical framework rooted in his long-standing engagement with montage and film history.20 At a moment when screen technologies are routinely associated with promises of connection, immediacy, collaboration, and flow, it may be more important than ever to retain a sense of their disjunctive operations and effects.21 From this perspective, Andersen’s claim that that the spectator who notices the location is not really watching the film takes on a new relevance. To reformulate this assertion slightly, one could argue that, today, the active displacement of attention is needed more than ever; we need an attention simultaneously attuned to the screened image and to its technical grounds. It is precisely by paying attention to the disjunctive environmental effects generated by screens that we might better grasp the evolution of screening techniques in our own time.

The literature here is too vast to summarize. A few of the essential positions include Bernard Tschumi, Architecture and Disjunction (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1996). On film as laboratory for architectural experiment, see Anthony Vidler, Warped Space (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2000), and Giuliana Bruno, Atlas of Emotion: Journeys in Art, Architecture, and Film (New York: Verso, 2002).

See, for instance, a number of the contributions in William Saunders, ed. Commodification and Spectacle in Architecture (Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota, 2005).

See, for instance, Dietrich Neumann, ed., Film Architecture: Set Designs from Metropolis to Blade Runner (Munich: Prestel, 1996); Mark Lamster, ed. Architecture and Film (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2000); and Bob Fear, ed. “Architecture and Film,” special issue, Architectural Design 70, no. 1 (January 2000); and Hans Dieter Schaal, Learning from Hollywood: Architecture and Film (Stuttgart: Axel Menges, 2010).

This was argument has been developed in Craig Buckley, Rüdiger Campe, and Francesco Casetti, eds. Screen Genealogies: From Optical Device to Environmental Medium (Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam Press, 2019).

Recently, the question of grounds and backgrounds has re-emerged as an important topic for art history and media studies. See, for instance, Hito Steyerl, “In Free Fall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective,” e-flux Journal 24, see ®; David Young Kim, Groundwork: A History of the Renaissance Picture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2022), as well as Weihong Bao’s forthcoming book Background Matters: The Art of Environment in Modern China.

For more information on Dawn, see Craig Barron and Mark Cotta Vaz, The Invisible Art: The Legends of Movie Matte Painting (New York: Chronicle, 2002), 31. His earliest film was an architectural travelogue, California Missions (1907), which used glass matte paintings to optically restore buildings that were largely ruined at the time.

One of the conditions driving the insertion of drawings into photomechanical backgrounds was the growing use of site photographs in competitions. For more on these early images, see Martino Stierli, Montage and the Metropolis: Architecture, Modernity, and the Representation of Space (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2018), Craig Buckley, Graphic Assembly: Montage, Media, and Experimental Architecture in the 1960s (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019); and Andreas Beitin, Wolf Eiermann, and Brigitte Franzen, eds., Mies van der Rohe: Montage Collage (Aachen: Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst, 2017).

For an exemplary reading of the tension between Mies’s 1922 model for a glass skyscraper and its sculpted clay backgrounds, see Spyros Papapetros, “Malicious Houses: Animation, Animism, Animosity in German Architecture and Film—from Mies to Murnau,” Grey Room 20 (Summer 2005): 6–37.

For a foundational account of the tension between the avant-garde and propagandistic uses of photomontage, see Benjamin H.D. Buchloh “From Faktura to Faktography,” October 30 (Autumn, 1984): 82-119.

Many of the ideas presented in this essay were developed in my Graphic Assembly: Montage, Media, and Experimental Architecture in the 1960s, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019).

For a vivid account of this process, see Gian Piero Frassinelli’s account of making the Superstudio’s photomontages on the website Drawing Matter. See ®.

Superstudio, “Discorsi per immagini,” Domus 481 (December 1969): 44.

Recent theorizations of cultural techniques broadly emphasize how media do not serve to disseminate pre-existing meanings, but are operative chains of actions that precede and structure the very emergence of cultural concepts. For a helpful introduction see, Bernard Sieghert, Cultural Techniques: Grids, Filters, Doors, and Other Articulations of the Real (New York: Fordham University Press, 2015), and Bernard Geoghegan, “After Kittler: On the Cultural Techniques of Recent German Media Theory,” Theory, Culture & Society 30, no. 6 (2013): 66–82.

In 2021, the Impostor Cities project partially wrapped the Canadian pavilion in Venice with a green screen. When viewed through an augmented reality app, scenes from fictional films shot on location in Canada were overlaid on the architecture of the pavilion. Paradoxically, this digital background par excellence was pushed to the foreground, redefining the role of the facade.

Such a claim was the repeated provocation of the Impostor City project. See ®.

Koolhaas’s essay, “The Generic City,” reads as a riposte to Kenneth Frampton’s influential concept of critical regionalism, which stressed the need resist the “relentless onslaught of global modernization” through a critical return to regional tectonic and material traditions. See Kenneth Frampton, “Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance,” in The Anti-Aesthetic, ed. Hal Foster, (Seattle: Bay Press, 1983), 16-30.

Rem Koolhaas, “The Generic City,” in SMLXL, ed. Jennifer Sigler, (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 1995), 1250.

For a more sustained critique of the account of globalization in Koolhaas’s Generic City, see Esra Akcan, “Reading ‘The Generic City,’” Perspecta 41 (2008), 144-152.

See Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996).

For a succinct statement of Tschumi’s argument, see “Disjunctions,” in Architecture and Disjunction, (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1996).

The media sociologist Scott McQuire, in a similar spirit, has argued that the tension between displacement and emplacement are a defining feature of digital media in the contemporary city. See McQuire “The City as Media,” Perspecta 51 (2018), 145.

Impostor Cities is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and The Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto within the context of its eponymous exhibition, which was initially commissioned by the Canada Council for the Arts for the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale.