Since the mid-1990s, Erica Baum has been coaxing a fragmented poetry from the unlikeliest places, quarantining found snippets of text that never aspired to great significance and dilating both their scale and their associative potential. Early on, the New York-based artist moved her camera close to half-erased classroom chalkboards (“Blackboards,” 1994–96), releasing details of equations, diagrams, and language from the burden of signifying and making them simultaneously abstract and allusive (e.g. the slyly reflexive smidgen of chalked text “TO DEPTH”). Since then, Baum has focused primarily on worldly printed matter; in “The Naked Eye” (2008—ongoing) she took stipple-edged trade paperbacks from the sixties and seventies and photographed them side on, scraps of illustration and text peeking chancily through tightly formalized verticals. For all her scrambling, though, the conceptual dynamic feels legible. A second-wave wrangler of Pictures Generation insights, Baum aims to illuminate a covert, sometimes incriminating largesse in the discarded and to purposefully collapse together not only high and low, as we once called them, but visual and verbal, banal diagram and highfalutin abstraction, the Apollonian and the edgeless.

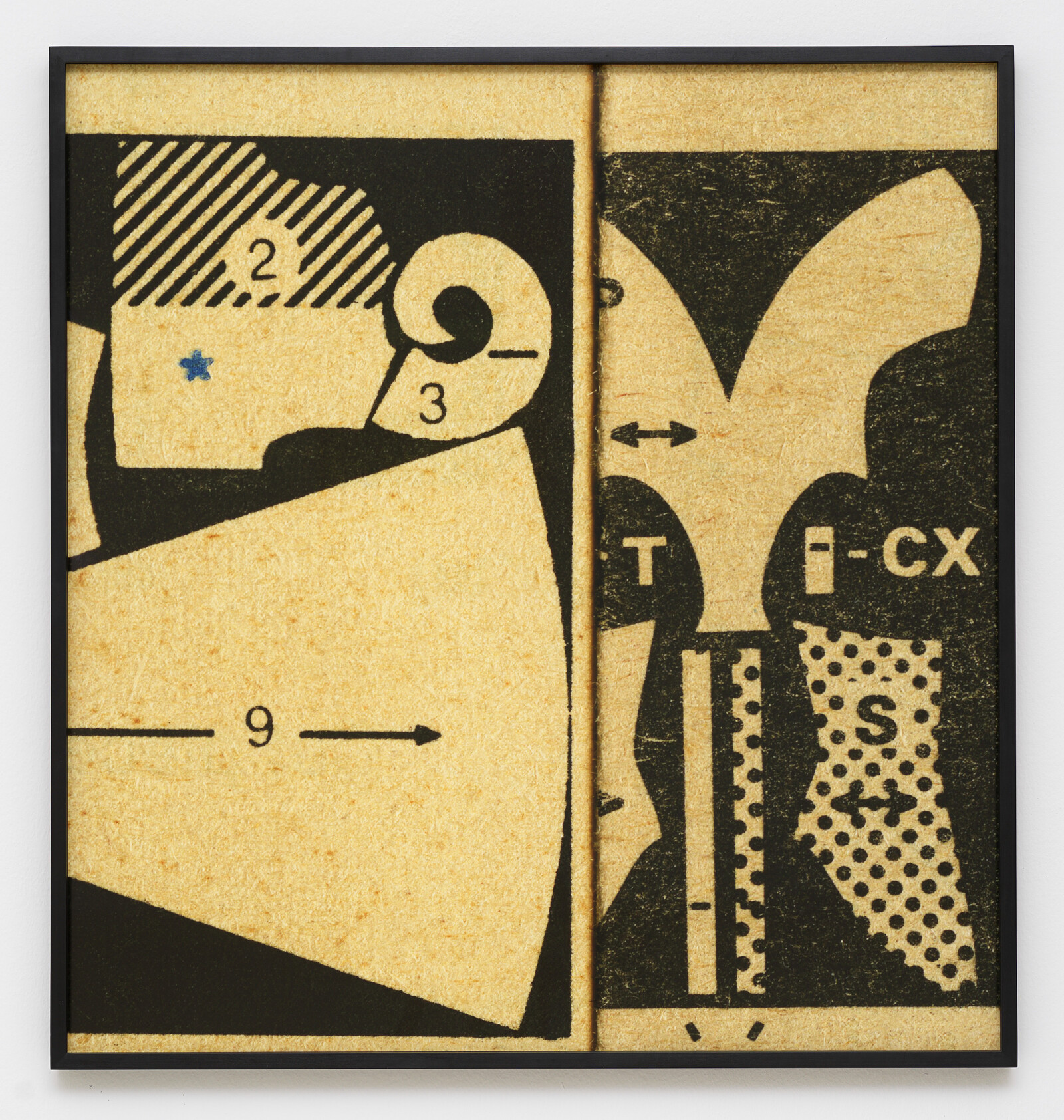

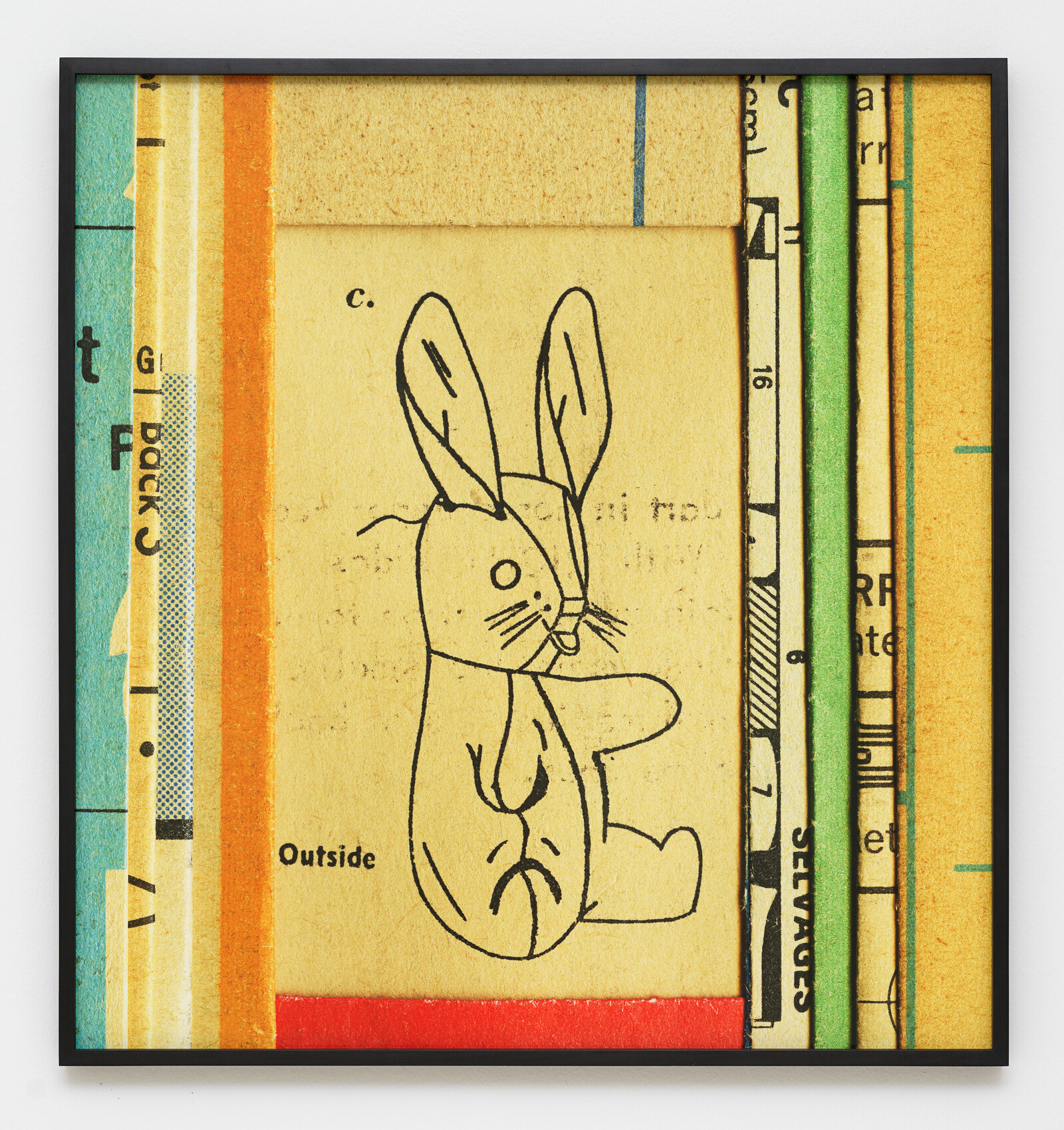

So she has a furrow and she’s ploughing it diligently, or, to extend the spatial metaphor, Baum is the sort of artist whose practice appears continually likely to run out of road, but then she finds another half-mile or so to cruise along. For the 2019 series “Patterns,” showcased by the twelve photographs in her latest exhibition at Klemm’s, Berlin, she’s alighted on faded sewing patterns for the home haberdasher, seemingly beamed in from the mid-sixties, printed on thin paper that allows for bleed-through of design and text. When Baum photographs these at varying degrees of distance, the result is a mixture of cleanly retro black-outlined imagery—a rabbit toy for children, slacks or knee-length dresses modelled by slim, stereotypically pretty women who could be minor characters in Mad Men—and compositions that abscond from representation because you can no longer see the wood, only a couple of trees. Or, technically, a snatch of graphic patterning in conversation with stranded and newly reverberant words.

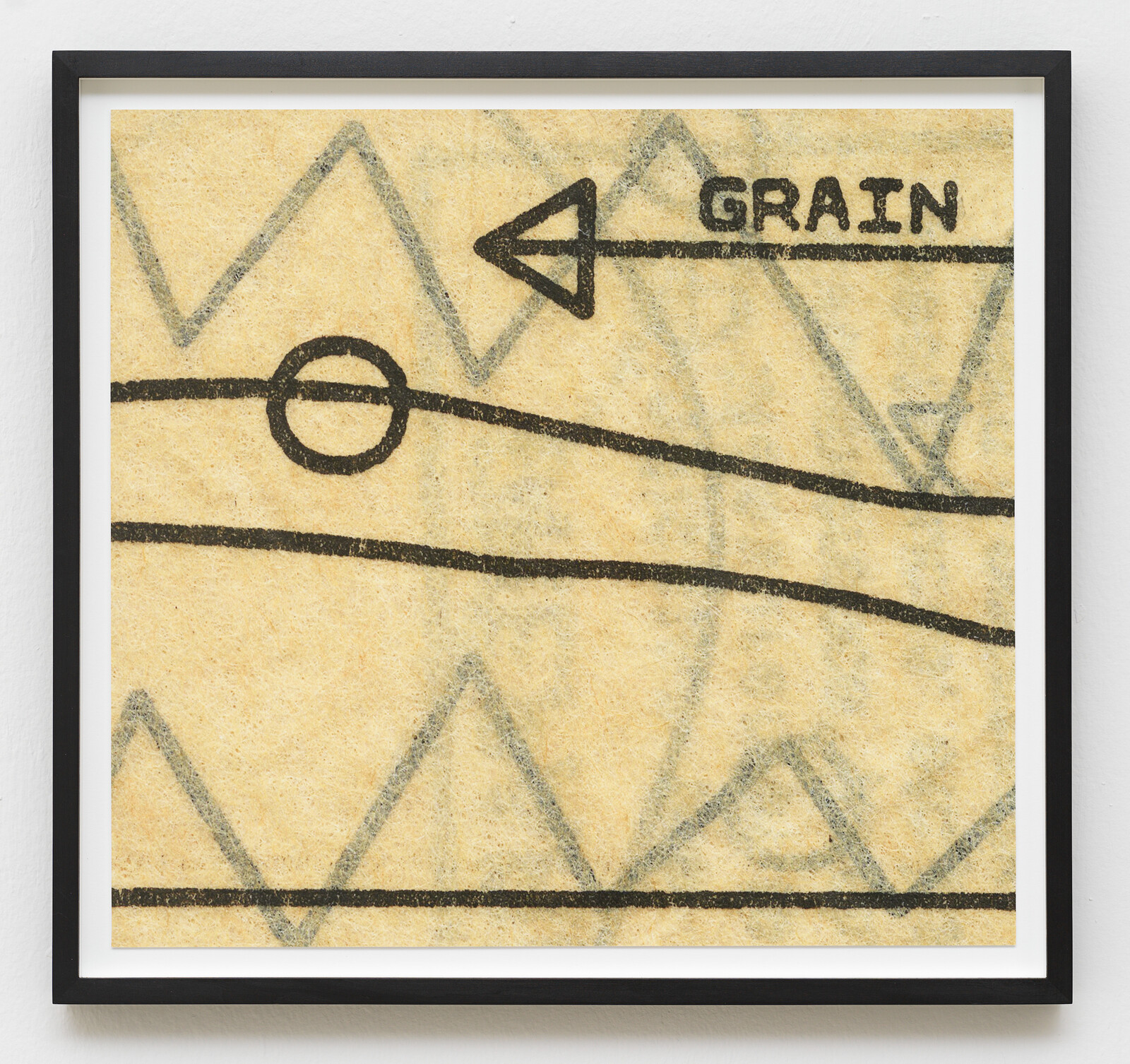

In Grain (all works 2019), a pair of wavering black lines thread across the yellowish pattern paper, the upper one enigmatically bisected by a circle, and converse with sawtooth-like markings on the verso. A firmly printed arrow shoots in from the right. It points, a textual addition clarifies, in the direction of “GRAIN,” a term relevant to pattern-making (you either cut fabric on or against the grain, i.e. along the bias), to the aesthetics of photography itself, and to the idea of the singular iota within a larger whole. To read a sewing pattern like this is to go against its grain of meaning in order to find a new seam, to allude to a cultural grain, to discern obscured patterns. In Skirt Green Red, the printed word “skirt” skirts both the lower edge of the photograph and the meaningfulness of modernist abstraction, embedded as it is in a composition of intersecting circles and lines that sit halfway between the ambits of Constructivism and the ostensibly more humble activity of dressmaking.

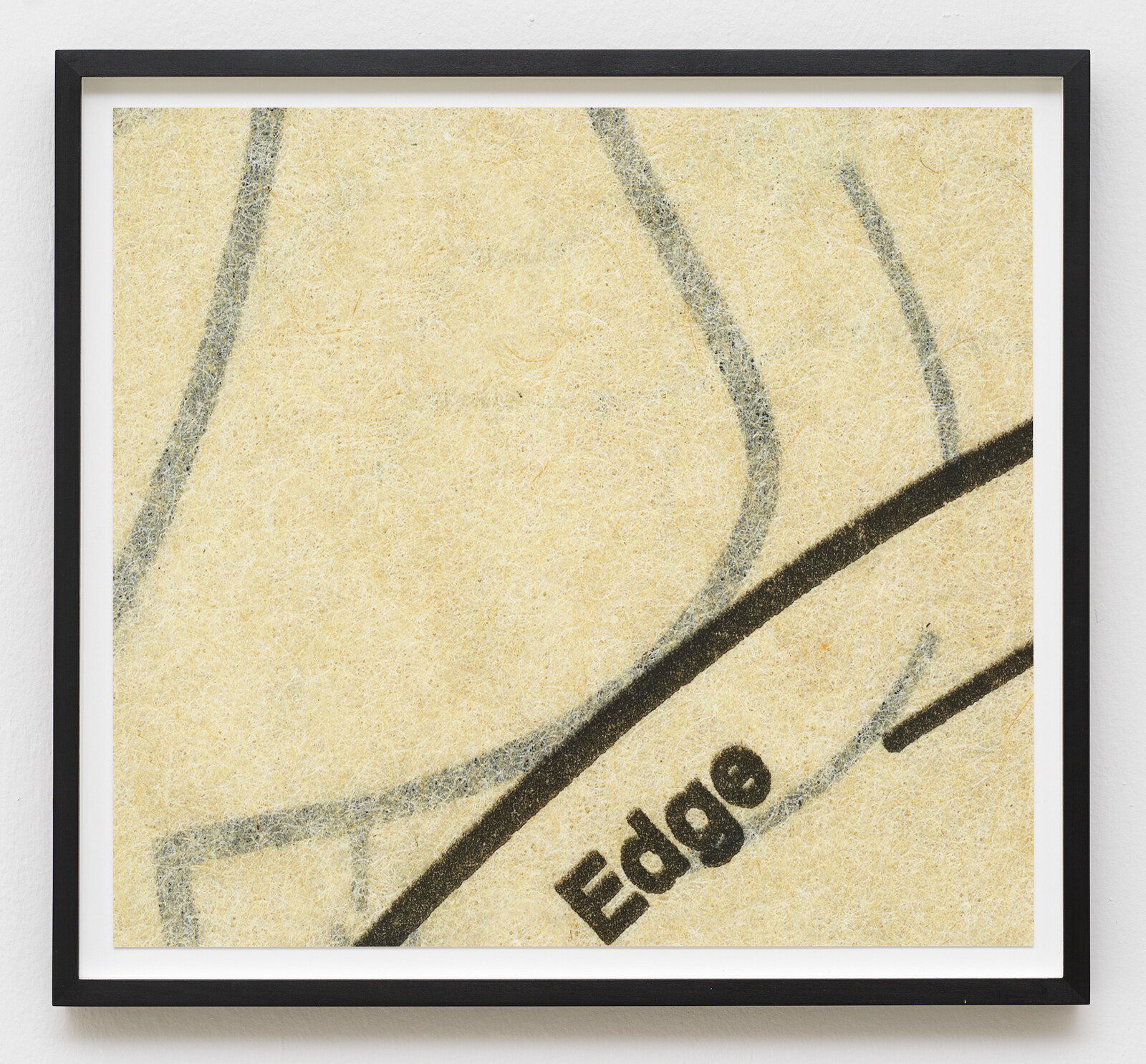

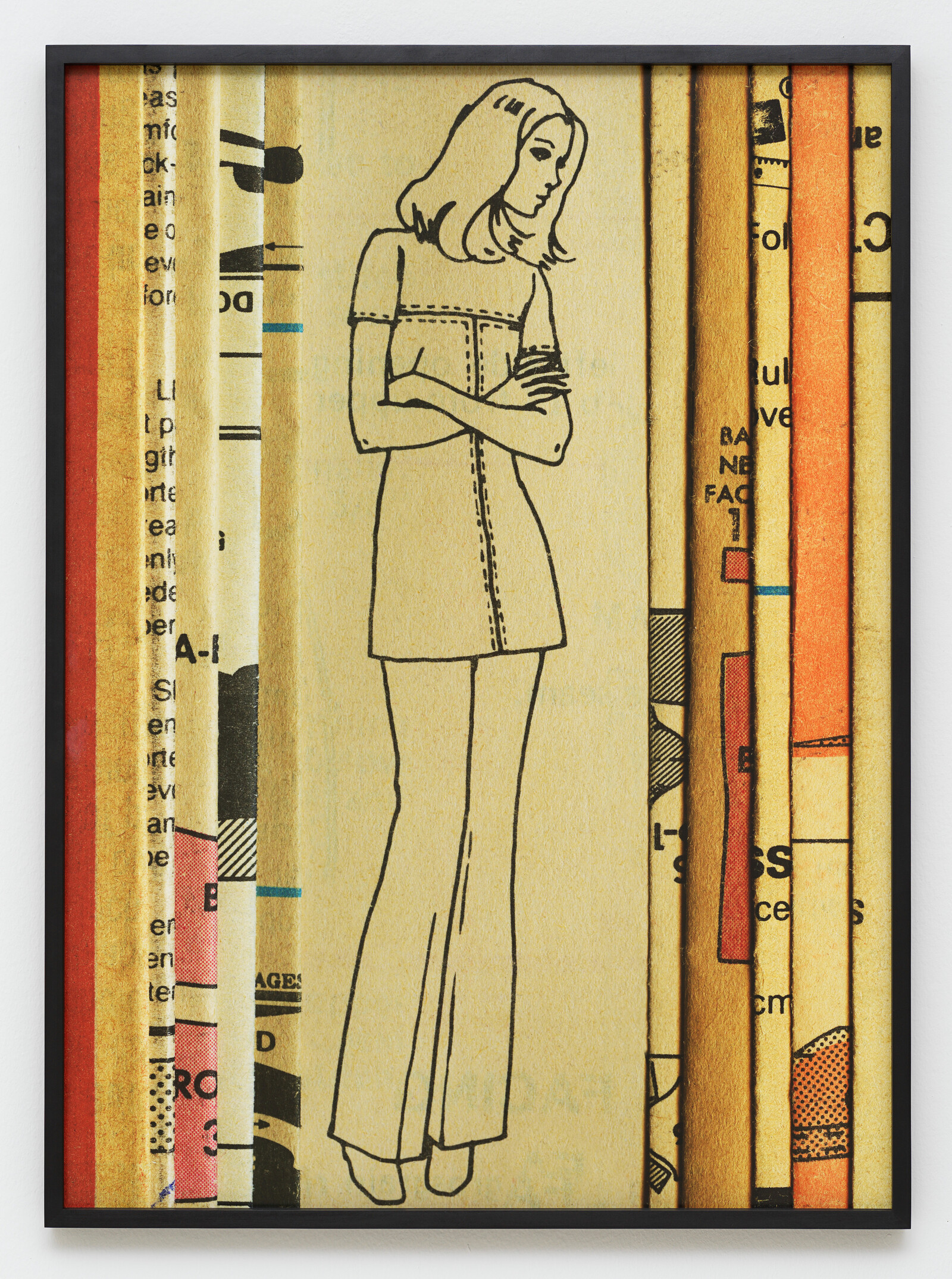

Here and in Arms Folded, where a diagram of a woman with arms protectively crossed is bounded by thin columns formed by folded-back pages of patterns—a range of possible dress-up options, templates for femininity—the embedded gender politics of Baum’s practice glints most strongly, hitched to a parallel refusal and undoing of power on the linguistic front. The exhibition might indeed be read as performing literal close reading, being split into photographs that clearly represent models wearing clothes, and ones where you’re pressed up against the pattern and meaning falls apart and realigns into speculative new formations. The work listed twelfth on the handout—actually the first thing you see on walking in, on a freestanding wall in the center of the one-room gallery—stars another stereotypical model, big eyes and a bob, outlined in black against sky blue. Her forefinger is on her lip, an expression the illustrator presumably imagined to be dreamily pensive. Baum, jamming codes, has titled the work Worry.

By the time you come round to it a second time, even the show’s title, “A Method of a Cloak,” may have come unstitched. At first you might assume that any cloaking is being done by the artist—taking formerly utile things and covering them in poetic opacity—but this too flips into duplicity, since cloaking here is also cultural: control woven into the fabric of normality. That Baum can use material from the sixties and, from beneath a genteel and unthreatening surface, have it speak to our still wildly unequal present feels hardly accidental. It’s a marker of sour times indeed that this very familiarity, as the ground shifts daily beneath our feet, can feel like momentarily solid footing.