Encompassing both surrounding environment and exhibition, tactile transitions define Hana Miletić’s solo show at LambdaLambdaLambda gallery. The first work in the exhibition, taken from a series collectively titled “Softwares” (2018–19) and displayed in the gallery’s entrance, is made from varieties of gray thread. This “pictorial weaving”—the term Anni Albers used to describe hand-woven artworks rather than fabric for everyday use—consists of a pattern vertically repeated four times.

Roving the streets of her hometown of Zagreb, or her current home of Brussels, Miletić documents found situations and portrays them in her work. One “Softwares” piece, dated 2018, is an abstracted image of a photograph Miletić took of something she saw on the street, a broken car window fixed with tape: the kind of makeshift repair people do when pragmatism is encouraged by financial necessity. Such traces of necessity and care—protection, maybe—are among Miletić’s central interests. The shape that defines the pattern of this “Softwares” work is also based, in part, on the machine it was made on: a Jacquard loom. Developed to produce household textiles, the loom’s efficient design replicates any given pattern four times. “Softwares” also evidences an artistic process of translation, in which a reparation becomes a photograph, then a pattern, and, finally, a textile. Only the contours of the initial physical situation made it all the way through this process, to its eventual representation in fabric. Material, memory, and reference are rendered in gray.

The same gray can be found in the shadow of history and labor, to which “Softwares” refers. There are the fabrics made by grandmothers, mothers, and daughters: warm blankets, curtains, tapestries, and whatever other tangible comforts are usually taken for granted—the invisible labor that makes for the cushioned backbone of life. The line of household work and female labor plays an important role in Miletić’s practice: in her family, weaving was collectively performed by women. The artist has reconnected with the activity in recent years, sometimes in the context of an all-female group (the works in this exhibition, however, were made by the artist herself). Miletić places important emphasis on the narratives of women in the shadows of men; women created the framework from which men thrived. Specifically, the mechanism that made Charles Babbage better known than Ada Lovelace. Lovelace contributed to the development of Babbage’s Analytical Engine—the first computer, for which the Jacquard loom was a predecessor—with similar binary traits. Vertical or horizontal lines became the ones and zeros embedded in binary code. The working methods of the loom were used to create the code, thus “Softwares.”

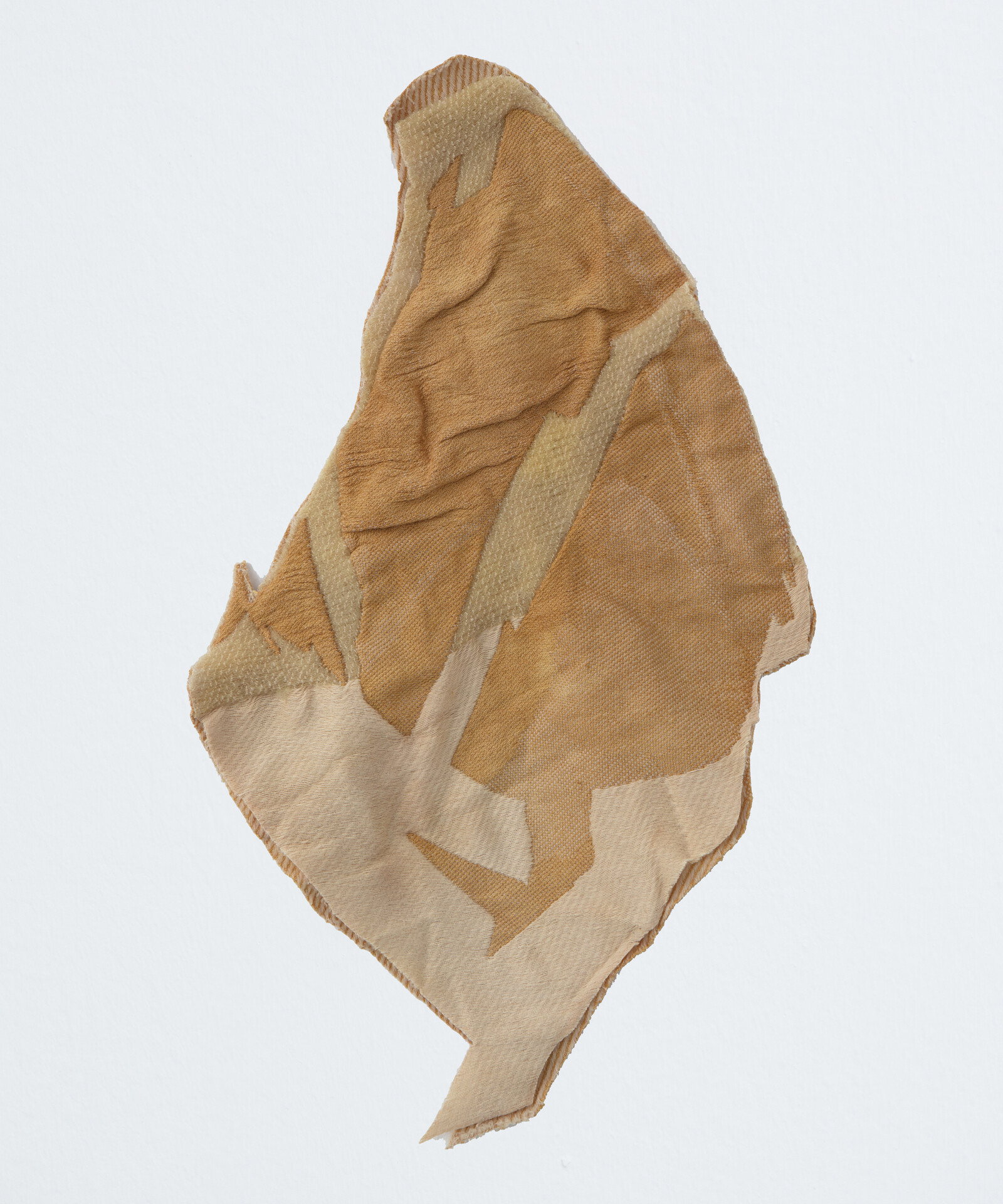

Working against binary logic and the erasure of women’s narratives, Miletić’s exhibition creates a space of nuance and alteration. Typically, weaving does not allow for questions: it is straight, either horizontal or vertical. No diagonals, no curves. She explicitly goes against such limited methodologies to create forms of counter-narrative. In the gallery’s second room, the white walls are decorated with a crenellated pattern picked out in gray, three more “Softwares” works, and a 2019 piece from the hand-woven “Materials” series are mounted to the walls. These works’ soft colors reveal the artist’s use of household dying processes (she colors some of her threads using berries, beets, and avocados). In their shape and pattern, which variously resemble hearts, flower buds, and rugs, the works reveal the modes by which she manually modifies her weavings to adjust their rigid nature—to create some space, some alterations in the straight patterns, adjusting the binaries of left and right, zero and one, black and white, into a gray area of differentiation and non-alignment. In the same way former Yugoslavia and Brussels are zones of cultural and linguistic overlay, Miletić moves outside restricted rules, conformist straitjackets, and wholesale standardization.

Almost a decade ago, Miletić’s main medium was photography. Nowadays, it merely informs her broader practice as a source, a visual point of reference that moves toward different mediums. She renders such transitions tactile. Whether these concern medium, language, body, or culture. Similar to her work process and the shapeshifting necessary to move between cities, the transformations in her work process imply continuous adaptations with different outcomes that bear only traces of an initial situation. Photography is thereby translated through the contemplation, travel, time, body, and the loom, into something else: handwoven textiles—less transient, at least as delicate.