This visual essay was assembled out of some spontaneous and short, and other carefully planned and longer, trips through Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. The images swing between urban “archaeology” and documentary photography in order to build a comprehensive archive and understanding of post-Soviet road infrastructure, including post-industrial urban transformations in remote and high-altitude cities and villages in mountains or desert areas.

Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan were scenes of intense geopolitical struggle between the British and Russian Empires, and later between the Soviet Union and the West. In the twenty-first century, these struggles have been furthered by recognition of hydrocarbon and mineral wealth in the region, as well as by the impact of China’s global Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The idea of modernity has been translated and implemented in different ways by different ideologies throughout the region’s history.

This ongoing research, titled “Insular Modernism,” aims to identify and document the artefacts and existing socialist architecture that connect a number of cities associated with the Silk Road narrative. An impressive network of roads and former trade nodes are currently involved in the BRI. Thus, the journeys and images are an attempt to unfold ongoing political and cultural influence that continues to cross and nourish the region.

The Osh Bazaar sits on Bishkek’s western side, far from both residential areas and the center of the city. But why does it share a name with another city—Osh, which is in the South of Kyrgyzstan—when it is located in Bishkek? Osh was an important regional hub and trading city during the time of the ancient Silk Road, and had the best bazaars in the region. Osh is considered the cheapest bazaar in Bishkek. There are always traffic jams and dust around the market. Goods are mainly imported from China, Turkey, and Russia.

The Palace of Weddings is an iconic work of socialist architecture built in 1987. Wedding palaces emerged in the Soviet Union in the 1960s as an architectural typology and social institution during the Khrushchev administration’s attempt to promote state atheism. Paradoxically, an institution originally intended to promote a homogenized secular culture and stamp out local religious traditions became a means of celebrating national culture. During demonstrations on January 17, 2019, activists protested in Bishkek’s public spaces against what they called the increasing number of Chinese migrants in Kyrgyzstan. The demonstrators also expressed support for ethnic Kyrgyz, who they said were being persecuted in reeducation camps in China’s northwestern province of Xinjiang.

When the “El Kutu” monument by sculptor T. Sadykov was first erected in 1995, it was decorated with twenty-nine prominent figures (writers, architects, composers, politicians, etc.) from the history of Kyrgyzstan. Some figures were stolen, while others were damaged, so Sadykov requested all of the figures be removed. In the last ten years, yet mainly during the 2011–2012 election period, 750 protests with over twenty-five-thousand participants took place in Kyrgyzstan. Protests increased again in 2019. All of those in Bishkek took place around El Kutu, and were focused on the role of China in the country’s political transition.

Karakol (formerly Przhevalsk) was founded as a Russian military outpost on July 1, 1869. The city grew in the nineteenth century after explorers came to map the peaks and valleys separating Kyrgyzstan from China. On our way there, we traveled along the Balykchy–Ananyevo–Karakol–Bokonbaevo–Balykchy highway (also called the Issyk-Kul ring), a 442-kilometer-long road developed during the Soviet Union. On the northern side of Issyk-Kul Lake (which translates to “warm lake”), the road is being rehabilitated. The road is part of the North-South strategic highway under development by the Chinese company China Road. Soviet bus stops along its path are being demolished one by one, while new ones sit waiting to be installed.

The Dungan Mosque was erected sometime between 1904 and 1907 as a place of worship for Karakol’s Dungan refugee population, which had settled in this newly-founded Russian military outpost in the 1880s after fleeing ethnic violence in China. The mosque was later named after Ibrahim Aji, the man who originally invited the famous Beijing architect Chou Seu and twenty carvers skilled in traditional Chinese architecture and composition to build the mosque.

Irdyk was the first village founded by Dungan migrants during the Russian Empire. Dungans moved to this area after the defeat of the anti-Qing uprising In China (1862–1877). The uprising began in Shaanxi province and spread to some areas of Gansu province. Irdyk is the largest of the five villages in the Irdyk rural district. The village has a secondary school named after Yusuf-Khazret, a village club, a library, a museum, and the largest mosque in the Issyk-Kul region. According to local legend, the architect who designed and built the mosque lived in this house.

When Yuri Gagarin visited Barskoon Valley, he climbed a stone that locals claim resembles the face of an astronaut for a photo. Later, Gagarin’s portrait was carved into that stone. After Barskoon Valley, the highest point along the mountain road is Kumtor Pass, about 4,000 meters above sea level. The road then leads to the gold mining enterprise Kumtor, which started operation in 1997 and is owned by the Canadian company Centerra Gold.

Near the border with China, this caravanserai is located in the At-Bashinsky district of the Naryn region in Tash Rabat. Buildings of this type are found throughout the Near and Middle East, and in Central Asia, in cities, on roads, and in non-populated areas that once served as shelter and parking for travelers and trade caravans. In the times of the ancient Silk Road, Tash Rabat served as a caravanserai for merchants and travelers on caravan roads from Transoxiana to Kashgar. The political and commercial importance of this road was notable from the second century BCE to the second century CE.

Along the northern side of the Issyk-Kul ring highway is a concrete “yurta” designed as a café, awaiting its summer guests. The construction of the North-South Alternative Road was inaugurated by former president Almazbek Atambayev on May 2, 2014. Construction was carried out by the Chinese company China Road, which has been operating in Kyrgyzstan for 18 years. In connection with this, Kyrgyzstan has received a soft loan of US$700 million from the Peoples Bank of China under a Shanghai Cooperation Organization program.1 Money went to build new transport arteries linking China with Uzbekistan and to transport cargo flows to Iran. Chinese goods will pass along these roads, but the people of Kyrgyzstan will have to pay the debts.

Naryn is located at an altitude of 2,000 meters above sea level, on the banks of the Naryn River, at the intersection of the Bishkek–Torugart highway. The 539-kilometer-long Bishkek–Naryn–Torugart highway is part of the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation Corridor 1 and the most important of the two main routes connecting China with Kyrgyzstan and beyond.2 It is one of the main transport arteries of the Kyrgyz Republic, connecting three regions of the country: Chuy, Issyk-Kul, and Naryn. Besides that, it provides access to Pakistan via the Karakum Highway and to the ports of the Indian Ocean, also allowing Russia and Kazakhstan to reach these ports.

The Burana Tower is a minaret situated in the small town of Tokmok in northern Kyrgyzstan. It was built in the eleventh century and was used as a template for later minarets, such as the one found in Bukhara. The site represents the last remaining part of the ninth-century city of Balasagun, which was ransacked by the Mongols in 1218, and by the fourteenth century had been completely destroyed.

About a decade ago there was a plan to turn Tash-Kumyr into something similar to Silicon Valley. “The Crystal” plant and a number of similar enterprises in other Soviet republics were built during the Cold War. In 1997, under President Akayev, “The Crystal” fell under the World Bank Privatization and Enterprise Sector Adjustment Credit program and went bankrupt in a matter of months.3 In 2017, the successor to Kristal LLC Quartz Company was planning to complete the construction of a plant for the production of technical silicon, but something went wrong and that company too went bankrupt. In 2018, a number of facilities from Tash-Kumyr, including a pumping station, water treatment facilities, and water supply and sewage systems, were sold at an open auction to the Chinese company Hydropower Development Wang Chuan Guangxi. The future of the plant and associated facilities is uncertain.

The Kurpsayskaya Hydroelectric Power Station is state-owned and sits along the Bishkek–Osh Highway. near the village of Razan-sai. Kurpsayskaya is the second of the cascade of hydroelectric power stations along the Naryn. It is located forty kilometers away from the Toktogul Hydroelectric Station in the Nooken district of the Jalal-Abad region.

Museum Sulaiman Too, Osh, Kyrgyzstan, 2018. Image: Ștefan Rusu. © Insular Modernities.

For more than one and a half millennia, Sulaiman Too has been revered as a sacred mountain by travelers. Its five peaks and slopes contain numerous ancient places of worship and caves with petroglyphs, as well as two largely reconstructed sixteenth-century mosques. The museum located in one cave is made up of two separate levels. Visitors enter through the lower level, which is entirely made of artificial caves. The second floor, made of a natural cave, opens through the front façade to a panoramic view of Osh. At the base of the mountain is another museum, called the Silk Road Museum. The Sulayman Too is the only UNESCO World Heritage Site in Kyrgyzstan.

Jayma Bazaar stretches for a kilometer along the western bank of the Ak-Bura River and is considered one of the most colorful and largest bazaars (in terms of goods traded) in Central Asia. It has existed in the same place for more than 2,000 years, since one of the branches of the ancient Silk Road passed through Osh. The bazaar today is a container-filled market from the 1990s. Many wholesale and retail stores sell the same things. One can find everything here: food, clothing, household goods, textiles, souvenirs, and even livestock. Most products come from China, but everything is cheap and there is lots of choice.

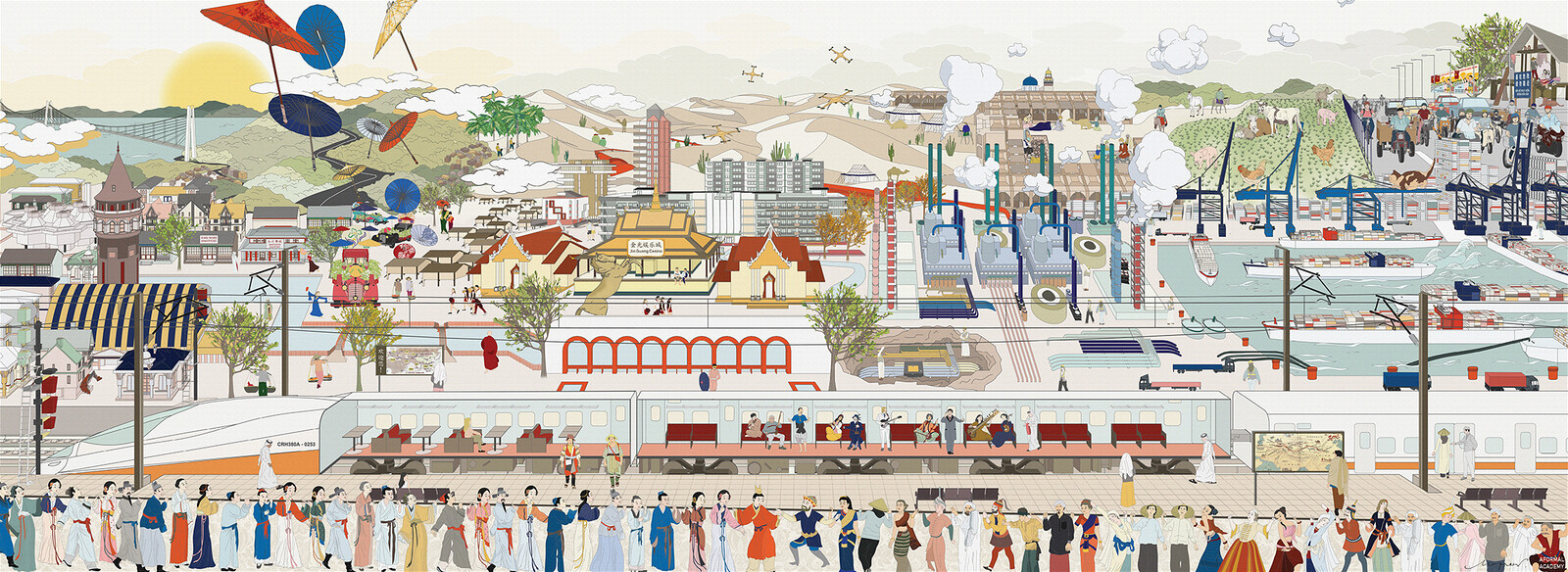

Khujand is one of the oldest cities in Central Asia. The Masjidi Jami Cathedral Mosque was built at the beginning of the sixteenth century as part of the ancient complex of the Sheikh Muslihiddin Mausoleum. On the square in front of the mosque are the buildings and tents of the central market. Mountains cover 93% of Tajikistan’s surface. To get to Khujand, one has to traverse the darkness and smog of the Anzob Tunnel, which takes about twenty minutes to pass through. The shortest road from Central Uzbekistan to the Ferghana Valley passes through Khujand, and from there continues on to Kyrgyzstan. As part of the Belt and Road Initiative, there are plans to develop a China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan railway project that will connect the currently-fragmented railway sections in the north and south of Kyrgyzstan and form an independent domestic railway network. It would shorten the route from East Asia to the Middle East and Eastern Europe by more than 800 kilometers, and reduce transportation time by five to six days.

The new masterplan for the Tajik capital, developed by the Russian Institute of Urban Planning and Investment Development, Giprogor, was approved by the government in 2013. According to the plan, eighty percent of the old buildings in the city, including dozens of Soviet-era buildings in the center, are set to be demolished. Teahouse “Rohat,” located on Rudaki Avenue—the main street of Dushanbe—was among them. On top of the demolition, the Tajik government is planning to build a parliamentary complex. Money for its construction was received from the Chinese government.

Nurek is among the most visited places in Tajikistan because of the Nurek Dam. Soon after the beginning of the hydroelectric power station’s construction on the Vakhsh River, the village of Nurek disappeared. A new city was built instead, where builders and hydroelectric workers from more than forty nationalities settled. The memorial to the builders of the Nurek Dam features the coats of arms of fifteen Soviet Republics, and was erected in 1972. Nurek was known during USSR as the “city of power engineers.” Today it has more than fifty-thousand inhabitants and a high unemployment rate.

Rohat Teahouse and Kokhi Vahdat were among fifteen buildings in the masterplan site to be declared national monuments and saved from demolition. Soon after, the rehabilitation of Kokhi Vahdat begun. The project involved a new façade and a terrible landscape design. Kokhi Vahdat is the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Tajikistan’s former House of Political Education. It was designed by a group of young architects led by Eduard Erzovsky in 1974. There are claims that China will pay for the rehabilitation project; there is a memorandum of understanding between Russia and Tajikistan to collaborate on the preservation of cultural heritage between 2021–2025.

The Pamir Highway is considered to be the second highest international highway in the world. The highway, which is also known as the M41, starts in northern Afghanistan and ends in southern Kyrgyzstan. The distances are huge, the terrain is wild, and on some portions it’s so remote that one can barely spot another vehicle.

Originally built in 300 BC, Yamchun overlooks large swaths of the Wakhan Corridor and parts of the Hindu Kush mountains in northern Afghanistan. The Wakhan Corridor lies between China, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Pakistan, inside the Pamir Knot. This strip of land, sandwiched between the four countries, was created as a buffer between the territories of British India and Czarist Russia in the nineteenth century. Because of its strategic position, the corridor was an important transit path for the ancient Silk Road in the fourth and fifth centuries. Chinese pilgrims passed through it to reach Buddhist centers in today’s Afghanistan and India.

Bulunkul is one of the coldest places in Central Asia, located just sixteen kilometers from the M41. It is a small village with forty-five homes and 300 residents.

Murghab is the biggest town in the Pamir Mountains. The population totals about 6,000 people, and includes both Pamirians and the Kyrgyz. At an elevation of 3,618 meters, there is a shortage of water, and electricity is only available at set hours. Yet Murghab is a must-stop place for travelers, as there is no other populated settlement around it for hundreds of kilometers.

The Pamir Highway stretches for almost 1,200 kilometers over much of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan through the Pamir Mountains, starting from Osh and ending in Dushanbe. A trilateral agreement was signed in Dushanbe to connect Tajikistan and Pakistan via the Durah Pass during the tenure of Burhanuddin Rabbani, Afghanistan’s president from 1992–1996, after a feasibility survey to assess the best possible route to connect the two countries.

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization, ➝.

Asian Development Bank, Kazakhstan: CAREC Transport Corridor 1 (Zhambyl Oblast Section) (Western Europe–Western People’s Republic of China International Transit Corridor) Investment Program (Project 1), February 10, 2015, ➝.

The World Bank, Kyrgyz Republic - Privatization and Enterprise Sector Adjustment Credit (PESAC) (Washington, DC: World Bank, 1997), ➝.

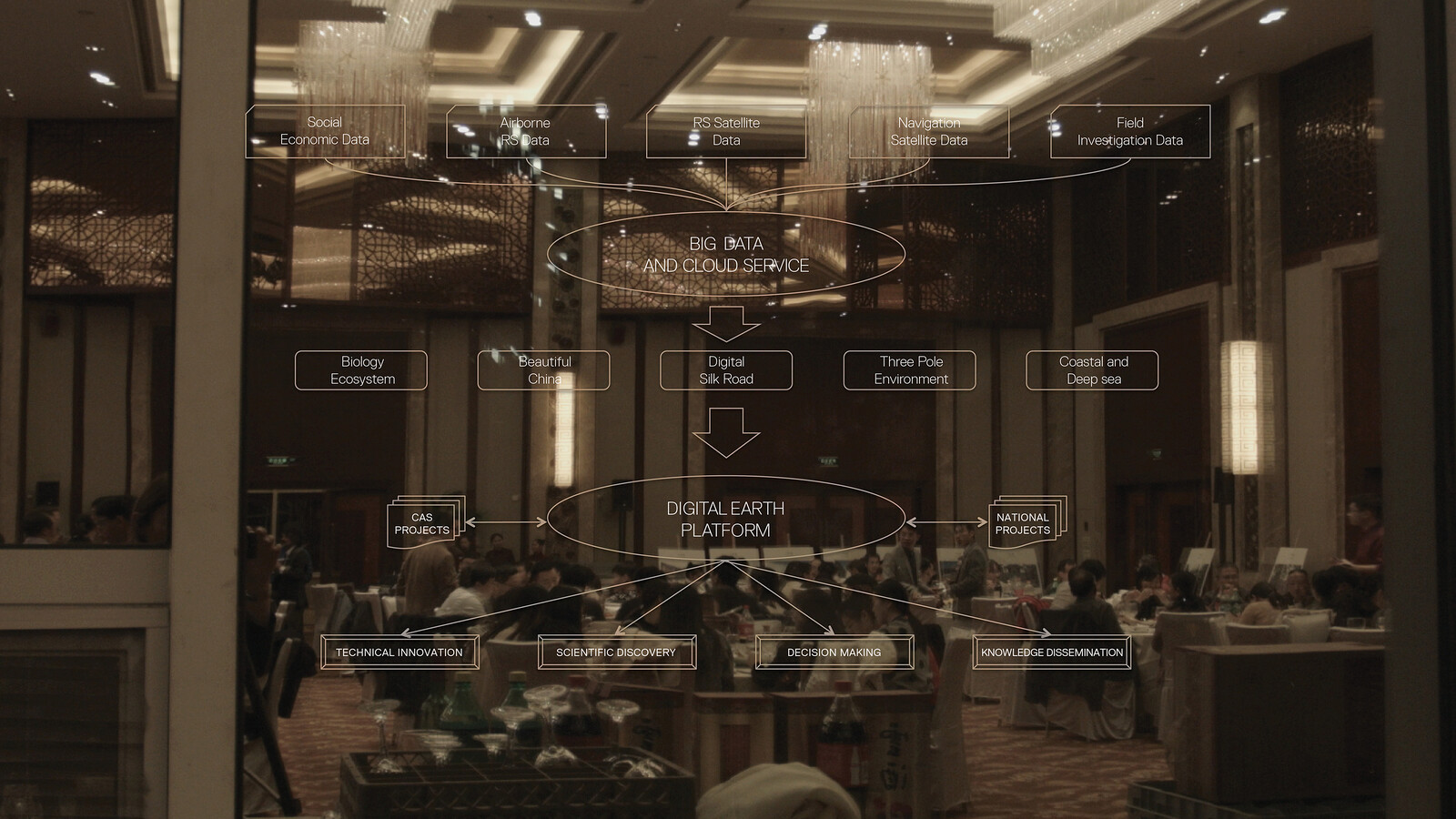

New Silk Roads is a project by e-flux Architecture in collaboration with the Critical Media Lab at the Basel Academy of Art and Design FHNW and Noema Magazine (2024), and Aformal Academy with the support of Design Trust and Digital Earth (2020).