What is the opposite of an exodus? Not the flooding of people into a city, but its emptying out by a kind of implosion—the city withdrawing into itself, its civic lifeblood sucked indoors. We don’t have a word for that. Curfew evokes it, but curfew is a time not a space, nor a movement of people. Nighttime is another condition with similar effects but is hardly absolute in cities that never sleep. Empty streets at night can be menacing but are not strange. It is daylight that makes the absence of people worrying. The city without citizens is inherently uncanny. Milan’s Piazza Duomo deserted at noon, Venice’s Piazza San Marco devoid of tourists, LA’s freeways free of cars, Oxford Street with the pavement to yourself, a fox roaming casually through Covent Garden. These are the spatial symptoms of an event, a rupture in ordinary proceedings. This is plague space.

Images circulating in the press and on social media of streets cleared by the Covid-19 pandemic summon up a vein of urban aesthetics preoccupied with the empty city. This is one of those moments when life starts to imitate art, or at least when art forces itself on the interpretation of reality. From Renaissance paintings of ideal cities to contemporary architectural photography, the removal of people has been a potent aesthetic device for revealing the underlying order of things. It is a simple way of reversing the relationship of figure to ground. Architecture, usually the backdrop to some human drama, becomes instead the figure. The stage set takes a bow.

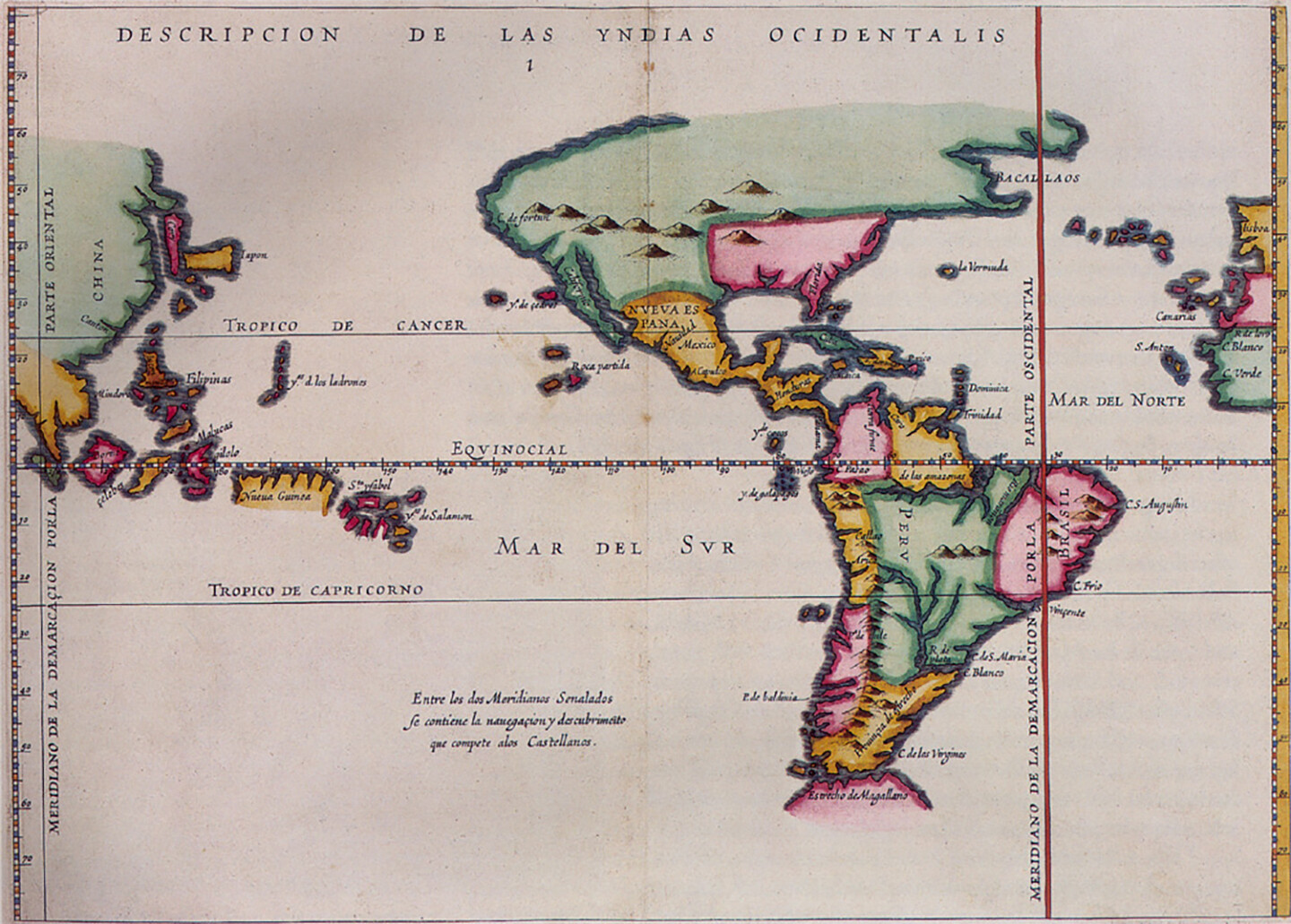

In that famous painting once attributed to Piero della Francesca and now to various others, The Ideal City (1480–1484), a piazza bordered by colonnaded buildings presents a perfect metaphor for an orderly society. This platonic world is there for us to live up to but remains uncorrupted by human presence. The painting is as eerie as today’s images of Milan, London, and New York. It reeks of that “invisible enemy” our politicians keep invoking, or of Don Delillo’s “airborne toxic event.” Atmospheric, maybe, but the atmosphere is exactly what we are supposed to be avoiding. When the city itself is no longer safe to touch, when our friends and neighbours are no longer safe to meet, the streets start to merge with videogame space: if anything moves, train your crosshairs on it. It is the presence of strangers that defines public space, and it is their very strangeness that makes it comfortable. Take away the strangers and public space suddenly becomes oppressive.

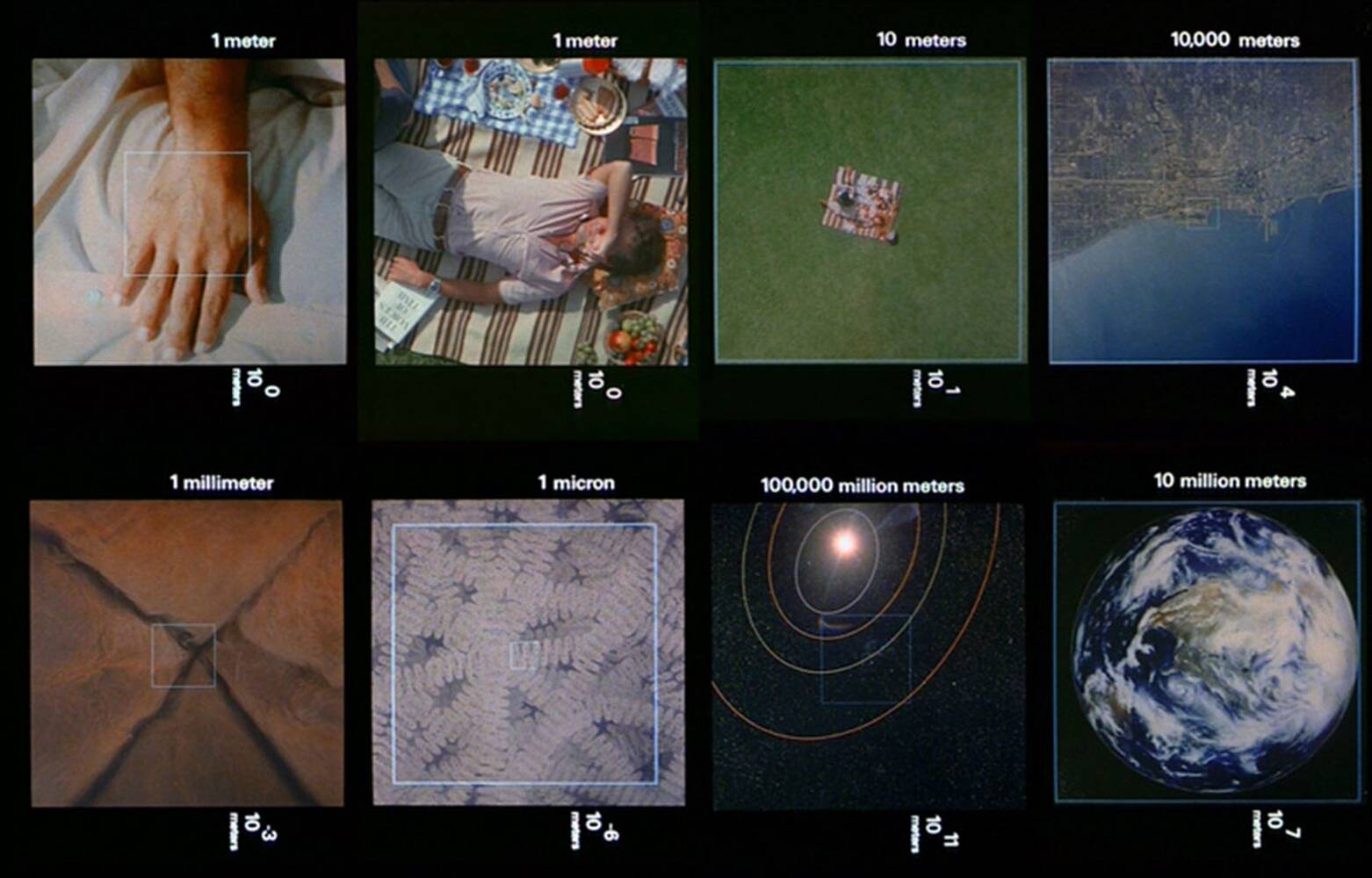

In his book The Weird and the Eerie, Mark Fisher observed that “a sense of the eerie seldom clings to enclosed and inhabited domestic spaces; we find the eerie more readily in landscapes partially emptied of the human. What happened to produce these ruins, this disappearance?” Fisher proposes that, unlike the shock of the weird, there is a certain thrill to the eerie in offering an escape from the mundane, from the day to day. This applies rather well to the images of urban desolation we are seeing today. Some of that frisson comes from the absence of people, but also from the proliferation of space. One of the supposed blights of late twentieth-century urbanism was an excess of space, by which logic airports and shopping malls were sprawling steppes of retail. Marc Augé called them “non-places” while Rem Koolhaas coined “junkspace.” But these images on the news are not non-places; they are places by definition, with landmark architecture and postcard familiarity. That is what is eerie.

I confess that I have sometimes viewed the strategy of photographing the empty city as a sort of gimmick. It was as though, merely by venturing out at 5am, the photographer could tap instant atmosphere, ready-made meaning. Emptiness seemed more a technique than a position. This was an uncharitable view. I would no more expect Gabriele Basilico to people his urban views than I would expect Giorgio Morandi to squeeze a face in among his jugs and vases. Figures have a tendency to demand attention. We are attuned to them as the carriers of narrative. But like Morandi’s paintings, Basilico’s photographs are concerned with other tensions: the rigours of objects in space, the placement of edges, the push and pull between solid and void, the rhythm of a façade.

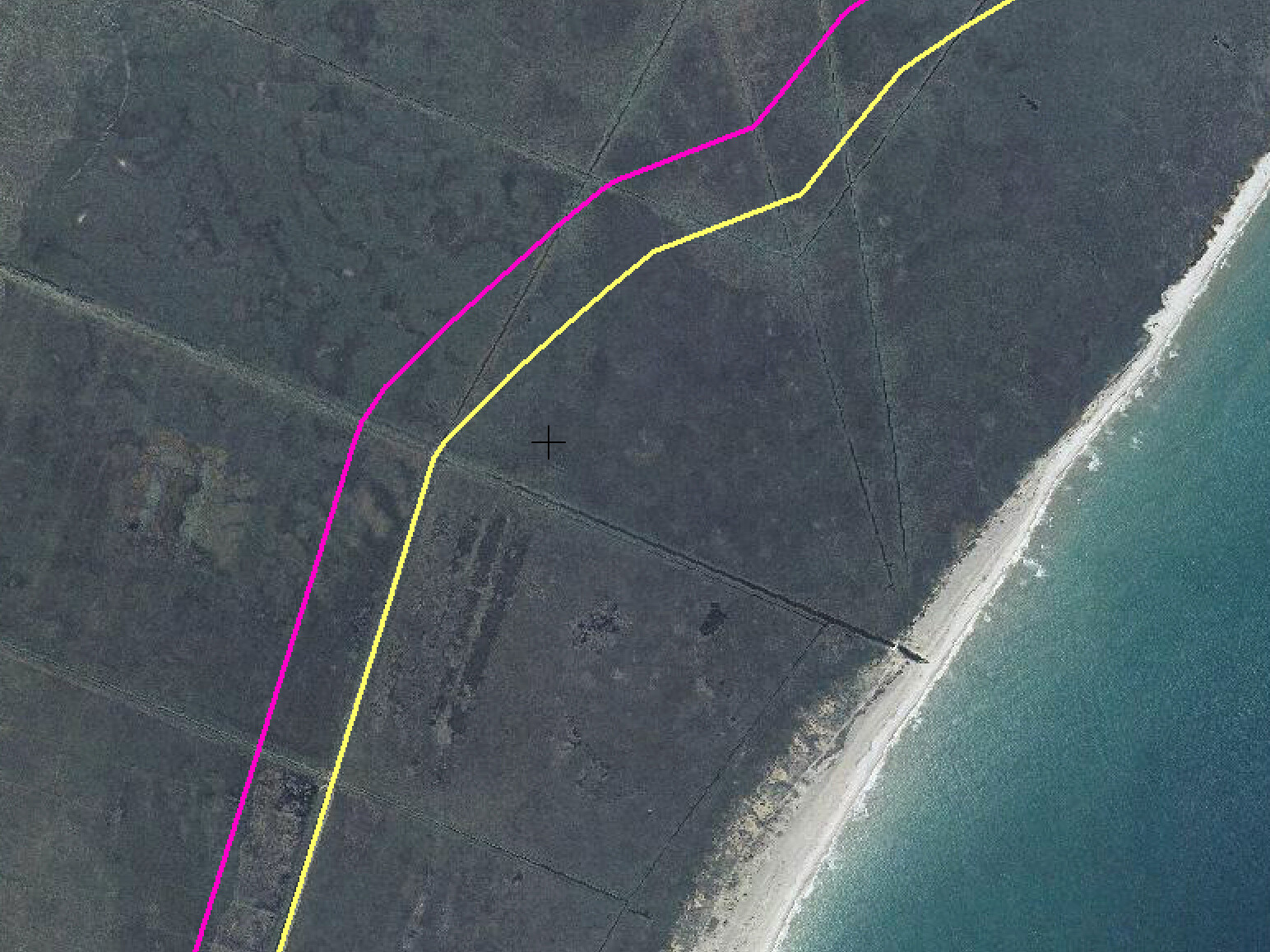

There are any number of photographers one could draw on in thinking about the void between buildings. Thomas Struth is a high priest of the empty city, whose photographs of deserted streets seek out a sort of collective unconscious of urban space. I’m not sure why Basilico’s less famous photographs come more readily to mind—probably because as I write Italian cities are at the center of the pandemic. With Basilico, the city emerges as a stage set without the players. The architecture is the narrator and its body tells its own story. One of his first photographic studies was Beirut in 1991. The city revealed its own history of human drama, scarred and crumbling after years of civil war. Francesco Bonami has written, fittingly, that Basilico was “like a doctor examining a patient who has survived a deadly disease. He observed destruction and at the same time acknowledged the incredible possibilities offered by survival.”

Recent photographs of Milan, Rome, and Naples evoke Basilico’s studies of Italianate urbanity: grand set pieces of ancient and modern coexisting in silence, or at least visual silence. On social media those façades are alive with viral videos (apposite term) of people singing and playing instruments on their balconies. Those scenes recall that Walter Benjamin essay about how Naples was porous with the sounds of public life, except that it’s now all one-way traffic spilling out from the apartment blocks.

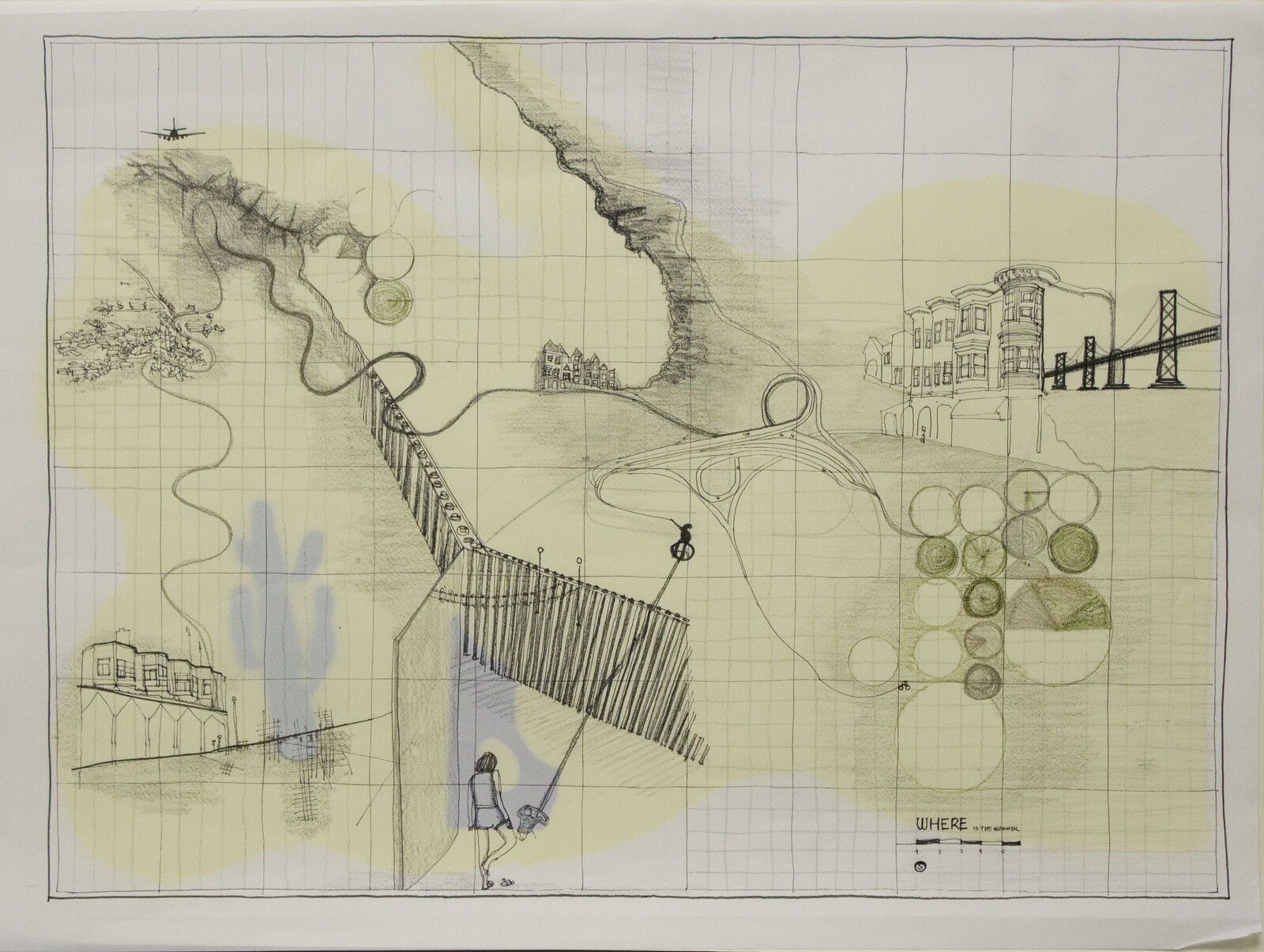

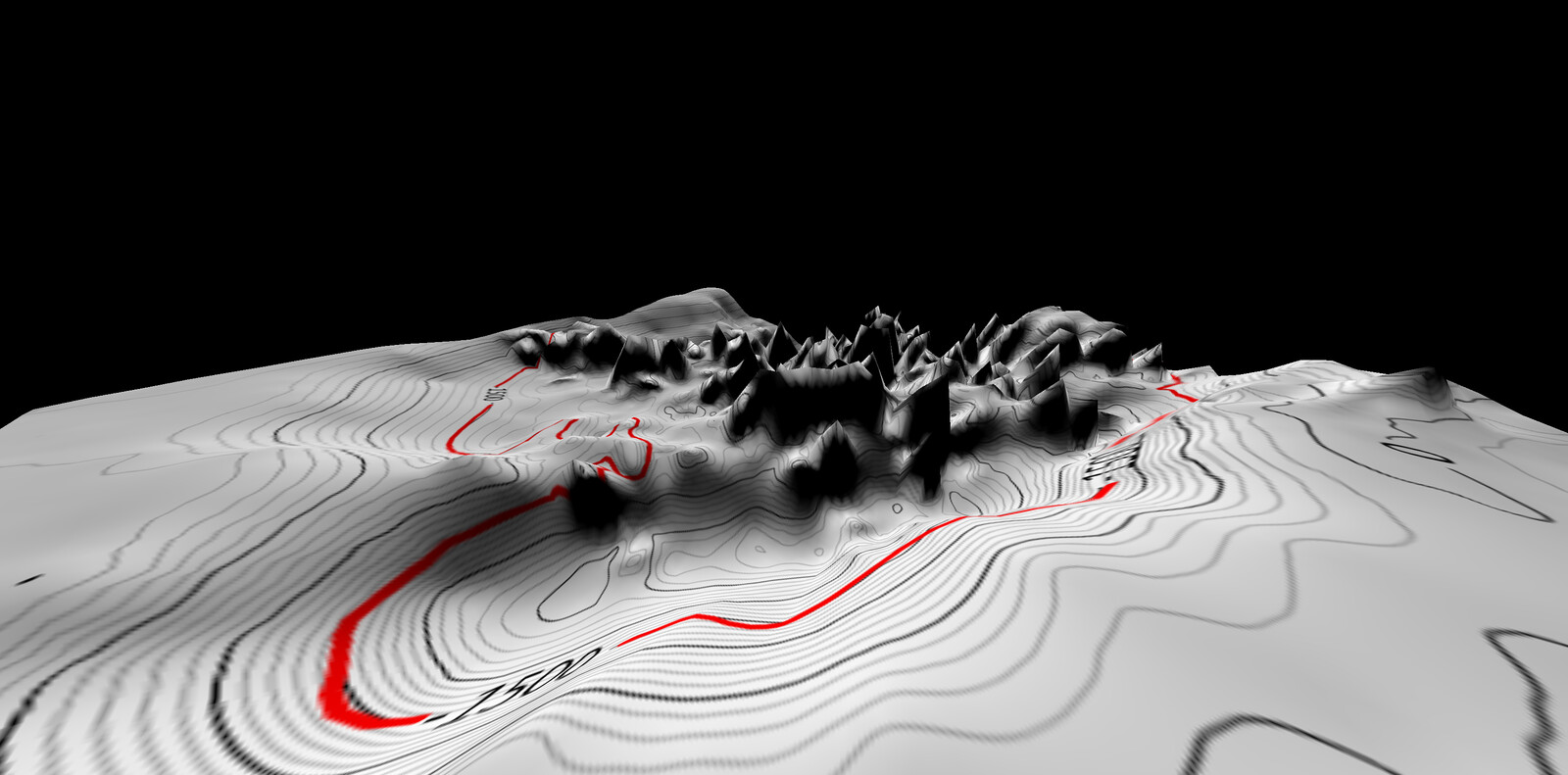

Whichever way you configure such scenes—whether as pictures or as architectural plans—emptiness is ascendant. The figure-ground plans of cities used by postmodern architects like Colin Rowe were meant to reveal the space between buildings, the res publica, as a life-giving force. The division of the city into black blocks and white streets or white piazzas made public space more tangible and thus more mutable. The emptiness was there to design with and around in the creation of a more thoughtful urban fabric. The irony is that now that we are so conscious of that public space, now that it is really visible, the public has gone. White space is dead space again.

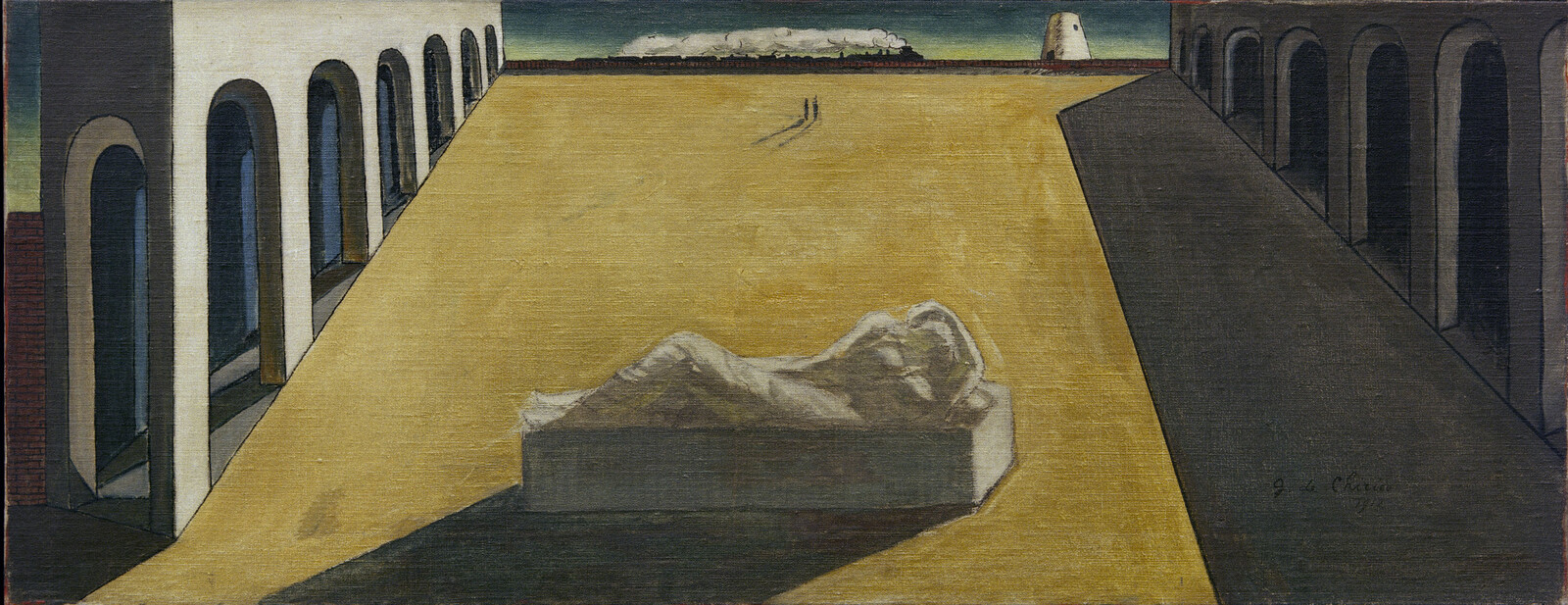

It is as though the master of Italianate emptiness, Giorgio de Chirico, had anticipated this. How especially vivid his early piazza paintings of the 1910s seem now, with their silent colonnades and their anxiety. De Chirico’s psychological landscapes use a template of Italian urbanity to stand in for the city, with vast squares framed by arches in exaggerated perspective. The emptiness is palpable, the sense of space oppressive. In The Lassitude of the Infinite (1912), for instance, tiny figures trek across a vast piazza that is more akin to a Soviet square, built for military parades and not the passeggiata. The figures are inconsequential; it is the void that matters, and de Chirico makes the emptiness material. “The hideous discovered void has the same soulless and tranquil beauty as matter,” he wrote.

Rereading Camus’s La Peste, as so many are these days, I picture de Chiricesque space, complete with arcades and hard shadows:

It was four in the afternoon. The town was warming up to boiling-point under a sultry sky. Nobody was about, all shops were shuttered. Cottard and Rambert walked some distance without speaking, under the arcades. This was an hour of the day when the plague lay low, so to speak; the silence, the extinction of all color and movement might have been due as much to the fierce sunlight as to the epidemic, and there was no telling if the air was heavy with menace or merely with dust and heat. You had to look closely and take thought, to realize that plague was here. For it betrayed its presence only by negative signs. Thus Cottard, who had affinities with it, drew Rambert’s attention to the absence of the dogs which in normal times would have been seen sprawling in the shadows of the doorways, panting, trying to find a non-existent patch of coolness.

London, too, has experienced that tangible void. Daniel Defoe’s diary of the plague in 1665 records the empty streets, save for the carts of the dead, and the way those who ventured out walked down the middle of the road to avoid contact. The phrase du jour is “social distancing” or, to the more socially minded, “physical distancing.” Either way, the point is distance, and distance creates its own voids. No artist explored that more exhaustively than Alberto Giacometti. His paintings in particular wear the strain of that distance, and the artist’s struggle to capture his fleeting perception of a figure. Heads and torsos shrink into the middle of the canvas as if they are getting further and further away. Around them, the sense of space becomes cavernous, and so Giacometti draws new frames inside the canvas, as if bringing the edges in to help contain this intolerable void.

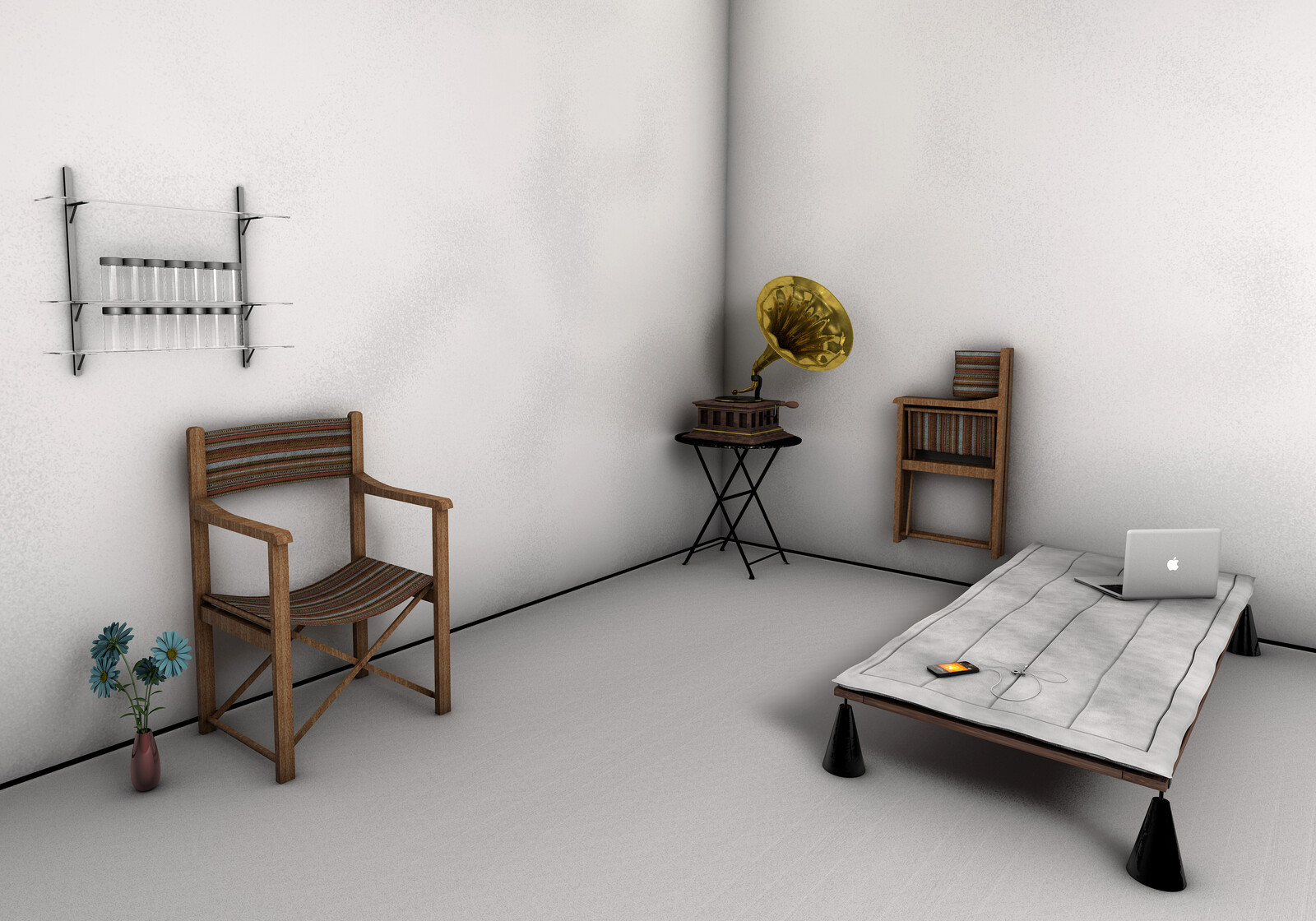

Art, as we know, can refresh itself in the light of events. Before last month, could one look at a Giacometti sculpture and feel anything other than over-familiarity? Could one still dredge up any of its original strangeness? Today I can. I’m thinking in particular of two sculptures from 1948 that depict urban scenes, City Square and Man Walking the in Rain. In City Square, four men walk toward or past a standing woman—possibly the most social scene in Giacometti’s entire oeuvre. Except that one senses little chance of an encounter, let alone a gathering; the figures have forcefields of space around them that would repel contact. The social distancing is hardwired. As for Man Walking in the Rain, every element of the sculpture contributes to the figure’s isolation. The street-like base stretches out in front and behind as if the road is infinite. Like the arrow in Zeno’s paradox, the man will never arrive. There is too much space, and it is pressing in on him, causing him to implode into an impossibly dense wireframe version of himself.

Camus’s main protagonist, Dr. Rieux, wonders at one point if his fellow citizens are not falling victim to an abstraction. But the virus is not an abstraction, any more than the sense of space it has unleashed. Space has physical and psychological effects. We have a heightened experience of it now in the brief moments when we venture out, if we do. We’ve felt the difference between looking at pictures of empty cities and the eerie sensation of looking around and realizing you are the only person on the street. What is understood as an uncanny emptiness is also an explosion of space, an expansion of distance: between mutually suspicious bodies, between citizens, between separated families. “Social distancing” is the perfect metaphor for the politics of our age–one of polarization, of filter bubbles, of them/us, of “hostile environments.” The emptiness is there to be bridged when life returns to the streets.

At The Border is a collaboration between A/D/O and e-flux Architecture within the context of its 2019/2020 Research Program.