Sand is a material that I have often overlooked. At the same time, I can be overwhelmed by the immensity of it, and the idea that each tiny grain, once amassed in large quantities, determines how coastlines form and evolve over time. Similar to the sea, sand is fluid—it is the liminal space between the land that humans can inhabit and the uninhabitable sea. While I always knew that black sand was formed as a result of volcanic activity, seeing the ashes projected violently into the air after the eruption of La Soufrière, the volcano on St. Vincent and the Grenadines’ main island, on April 9, 2021, gave me a new understanding of how black sand beaches come into existence. The material ejected from the earth’s core constitutes the coastlines I have always been familiar with, but always took for granted.

La Soufrière began to show signs of an effusive eruption on December 27, 2020. For the next few months, the volcano began to erupt effusively, creating a dome within the crater.1 Then, on April 9, the volcano erupted explosively, forcing approximately 22,440 people in the northwest and northeast parts of the island to evacuate to public and private shelters in the south. While the high-risk areas (known as red and orange zones) were immediately impacted, the entire island was covered by ash of various grain sizes within hours of the first explosive eruptions. One satellite recording showed that the eruptions penetrated the stratosphere around twenty kilometers above ground. The explosive eruptions continued for nearly thirty days, with ash continuing to rain down on the entire island. Typically known for its lush greens and blues, the landscape was dramatically transformed, desaturated by the color of the ash.

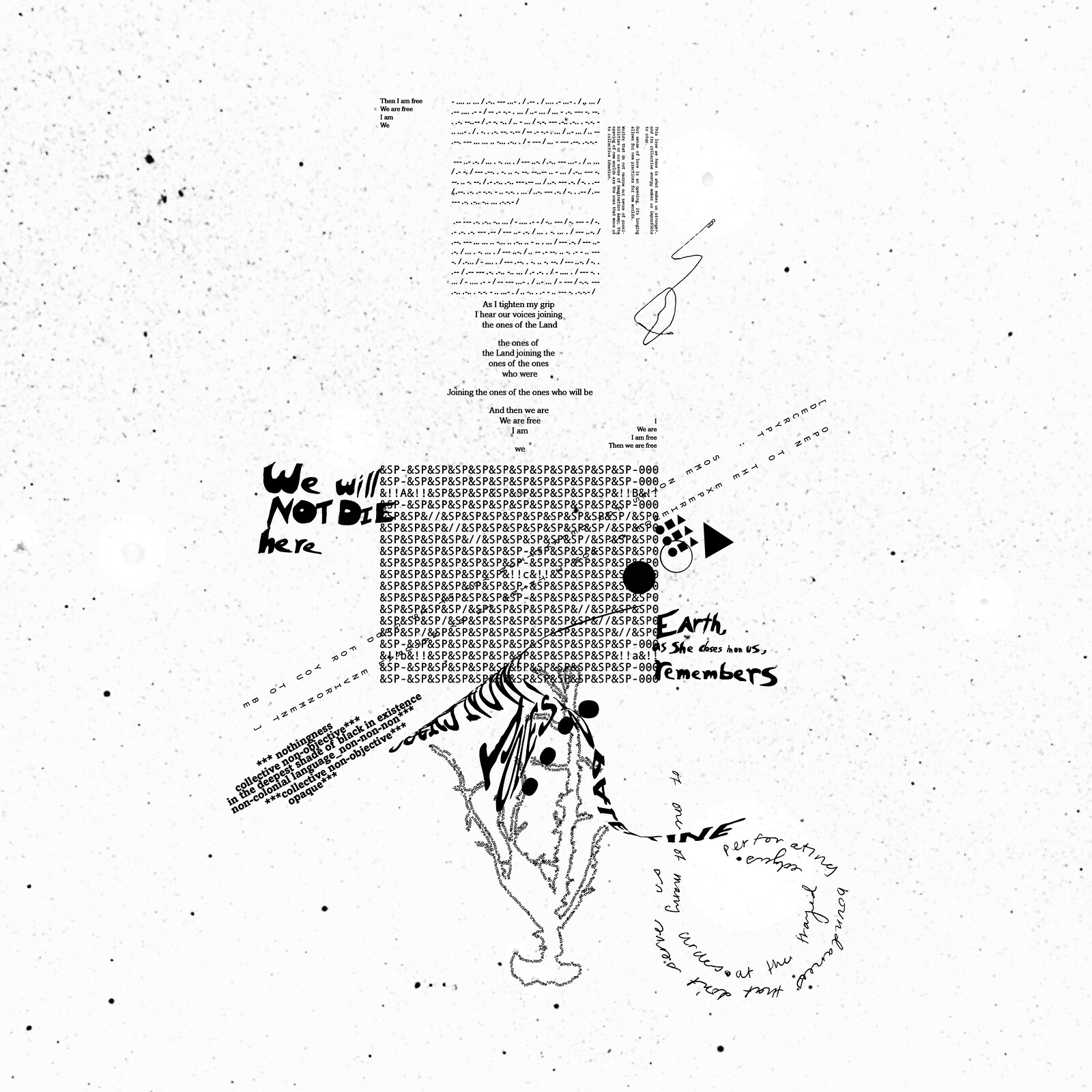

As a way to make sense of what was happening, I began the photographic series The Beginning is the End and the End is the Beginning (2019–2022). This work is an attempt to unlearn the aesthetics of documentary photography and the politics of the image in the midst of catastrophes. The images presented here, which are a fragment of the larger series, directly reference and depart from the aesthetics of archival images produced during earlier eruptions in the larger Caribbean, most notably the photographs by volcanologist Tempest Anderson during the 1902 eruption of La Soufrière.

The series examines the impact of the ash fallen and accumulated on terrestrial, coastal, and submarine environments, as well as on built environments. It departs from the scientificist and othering forms of representation that historical imagery reproduced in its quest for referentiality. It does so through a critique of hegemonic photographic parameters, resulting in a more instinctual relationship between the photographer—myself—and the eruptions. The series focuses on exploring intimacy in physical spaces during the eruption and my personal relationship with kin and friends during and after a volcanic eruption. This intimacy is also felt “outside,” in the liminal spaces the accumulation of ash created on the island.

Sandy Bay, St. Vincent. From the series The Beginning is the End and the End is the Beginning, May 30, 2021.

Sandy Bay, St. Vincent. From the series The Beginning is the End and the End is the Beginning, May 30, 2021.

Ash fall blankets the ground. From the series The Beginning is the End and the End is the Beginning, April 10, 2021.

Black and white sand, Indian Bay, St. Vincent. From the series The Beginning is the End and the End is the Beginning, July 4, 2021.

Sandy Bay, St. Vincent. From the series The Beginning is the End and the End is the Beginning, May 30, 2021.

Furthering this exploration of ashfall, I began observing huge differences in resilience and growth of coral reefs. Sand matters for the same reason that soil matters: the most vibrant forms of life are able to spring forth from it. Complex ecosystems such as coral reefs not only grow, but thrive in oceanic deposits of volcanic ash (now sand). Prior to the 2021 eruption, I had a long-term practice of documenting different forms of marine life, such as corals and sea urchins. As a form of citizen science, I am attempting to create an ecological archive and show visible changes that are happening within the marine environment over time. Coral Survey (2014–ongoing) explores the complexity of the marine environment in an effort to shift people’s perception of the sea and to gain a deeper understanding of how ocean health affects our own humanity. As a response to the validity of coral locations being questioned, the title of each image from this series contains the approximate GPS coordinates of what it shows.2 Just because we are unable to see something, that doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. On a more personal level, observing the everydayness within these submarine environments quells my own fears of the unknown and sparks new curiosities and imaginaries of the terrestrial worlds I inhabit.

Black sand, Troumaca, St. Vincent, 2022.

In terms of climate adaptability, especially within the context of the Caribbean, there is a critical need to protect our coastlines. Over time, coral reefs have adapted to natural phenomena—they have thrived and evolved in the wake of hurricanes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, and earthquakes. Europe’s colonization of the Caribbean not only involved the forced transportation of people, but also of soil, flora, and fauna. Today, it is difficult to visualize what Caribbean landscapes may have looked like in precolonial times, particularly in terms of botanicals. There are significant marine ecosystems that can be considered some of the few remaining native environments in the Caribbean. Coral reefs and sand preserve critical ecological nutrients that are necessary to sustain life across species, including for humans. My work is an attempt to archive these still-living, at-risk, and disappearing ecosystems, which contain valuable knowledge for our long-term survival.

13°18’28.2”N 61°14’07.0”W. From the series, Coral Survey, 2022.

13°18’28.2”N 61°14’07.0”W. From the series, Coral Survey, 2022.

13° 8’ 12.528” N 61° 12’ 29.238” W. From the series, Coral Survey, 2021.

13°18’28.2”N 61°14’07.0”W. From the series, Coral Survey, 2022.

The Caribbean’s dependence on what has been called “the tourist economy”—driven particularly by European and North American consumers—has led to the production of images that center idyllic, white sand beaches. By not accepting or valuing the actual and existing landscapes of the Caribbean, this has led to the development of a tourism model that actively works against attempts to conserve the environment and the long-term health of our coral reefs, and by extension, us. Developers and governments work hand-in-hand towards what ultimately feeds the ecocide of marine life by dumping white sand extracted from other environments onto native black sand beaches. My documentation of native black sand is an attempt to decolonize the image of what an idyllic Caribbean beach looks like.

Deposit of fresh volcanic material from the eruptions of La Soufriere volcano during April 2021. Troumaca, St. Vincent, 2022.

Caribbean people rarely question the movement of sand. Where is it being taken from? How will it impact its new environment? Will the new sandy material have any long-term effects on a coral reef that has evolved to thrive in certain types of conditions? The movement of sand from one location to another, whether it is to fill new beaches or to modernize coastal developments, seems to always tie into the lofty promises of a better future, whether those promises come from governments, investors, or real estate speculators across the Caribbean. Many failed models have been replicated across the region throughout history—models that have displaced and destroyed countless human and marine communities. As people around the world struggle to make sense of how to halt the imminent impacts of global warming, every little action counts on every level. My work does not dismiss the necessity for development, but rather attempts to challenge the tourism-driven models we adopt to drive our economies.

As an ecological archive, these photographs can be used both as evidence of the marine life and the submarine worlds I have witnessed, and to incite people to take action, to be persistent in challenging and holding decision-makers accountable. There is always a lesson for us in sand, no matter how small.

Loudreading is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, WAI Architecture Think Tank, and Loudreaders Trade School supported by the Mellon Foundation, re:arc institute, the Graham Foundation, Producer Hub, Iowa State University, GSA Johannesburg, Universidad de Puerto Rico–Rio Piedras, and the inaugural ACSA Fellowship to Advance Equity in Architecture.