They say ghosts, vampires, and the soulless cast no shadows. Shot in a Vatican City emptied of visitors during the pandemic summer of 2021, Catherine Opie’s new photographs provocatively reshuffle different threads of her longstanding inquiries—the spectrum from transparency to opacity; communal spaces; the body as/and architecture; queerness and institutions. With its succinct, descriptive enumeration, the exhibition’s trinitarian title “Walls, Windows, and Blood” implies unsettling visual conversations to which she gives form with a selection of images from three new series (all works 2023), clustered in grids, lined up along walls, and proceeding in colonnades.

No Apology (June 5, 2021), a large photograph of Pope Francis delivering a speech from a top-floor window of his residence overlooking St. Peter’s Square, greets visitors.1 A lone white man dwarfed by statuary and muffled by the resounding whiteness of the colonnaded plaza, he floats above a blood-red banner bearing his coat of arms. In his short allocution, uttered in the wake of the traumatic discovery of unmarked graves at the former Church-run Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia, the pontiff acknowledged (apologies would have to wait) the Catholic Church’s complicity in both the colonial dispossession of Canada’s Aboriginal communities and the accompanying systematic and racialized state violence.

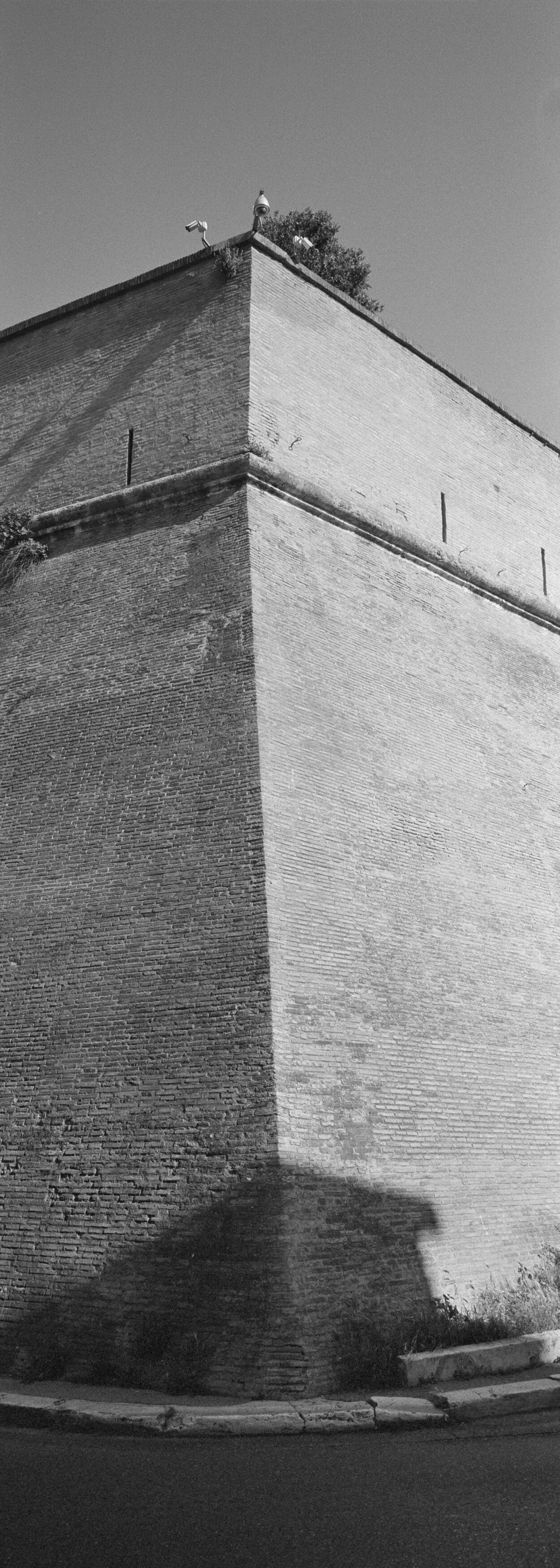

Four narrow, towering, black-and-white images lean, somewhat precariously, against a nearby wall, on low pink-marble pedestals: a selection from the “Walls” series, which registers every corner of Vatican City’s Leonine Wall from the inside. Opie’s use of the vertical format communicates a sense of enclosure, and the flesh-hued veining of the pedestals heighten the images’ objecthood. These photographs have sculptural presence: their pictured entrapment paints us into corners. In the next space, works from this series occupy the room’s actual corners—we find ourselves surrounded.

In Untitled #12 (Walls), a surveillance camera is aimed down from the rampart’s corner, under the cover of palm trees swaying over the fortification. Imported to Italy, palm trees are both a symbol of luxury and a visual reminder of the Church’s long history of expansionism, which seized on the colonial project to consolidate its power and line its coffers. Two embrasures pierce the wall, below the surveillance camera—a reminder that exclusionary violence has long enlisted vision to disguise itself as safety and security. But the writing, as they say, is on the wall. Yet, neither crenel nor lens can read the edifice’s most imminent danger. Their loftiness, like the Pope’s in No Apology (June 5, 2021), prevents them from grasping a stealthy and steady invasion: motley vegetation carving itself a home to seed, root, and sun on the fortification. An architectural equivalent to the tattoos, scars, and piercings familiar from Opie’s figurative works, this herbage writes a different story.

Across from this towering quartet, two images from the “Windows” series lend a certain air of mystery and anticipate the next room. Echoing Bernd and Hilla Becher’s systematic approach, this series of color photographs documents the outward view from every window of the Vatican. These observational images of colored, divided, patterned, screened, slatted, and hinged windows, variously open or closed, actively trade on transparency and opacity as well as reflection and refraction. They also hint at the window’s role in colonial capital’s redistribution of spaces, while inferring the porosity of borders and the interpenetration of spaces. The camera is a room and a window, an apparatus, a technology of vision.

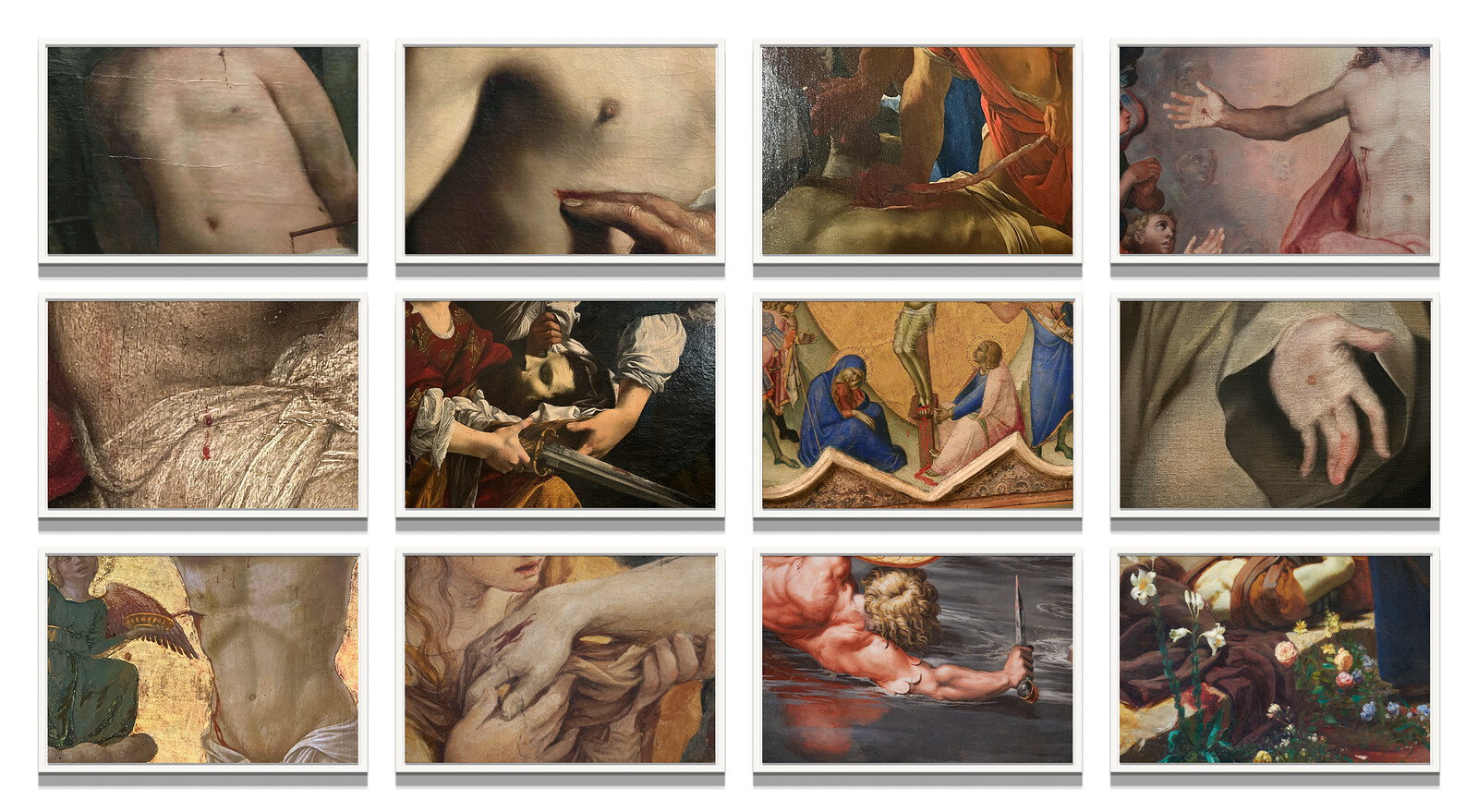

The same systematic approach marks “Blood Grid,” a series in which Opie tracks and documents every depiction of blood—every gloriously gory detail—in the works on display at the Vatican Museum. Ordered into grids of twelve, these smaller images echo contemporary crime-scene photos. Every painted gash and wound, every woven slit, spill, and drip also signals an artist’s stealing of a moment of freedom and delight in abstraction, a space of experimentation and material joy. Aiming to grant order to chaos, the grid—a seductive symbol of modernity—is, of course, imbued with violence.

Opie’s elegant play with the exhibition’s space packs a punch while also giving us room to ponder. The work shuttles us between repulsion and enjoyment, pushes us away, draws us near, and ultimately strands us in between, brilliantly, like Opie’s shadow in Untitled #3 (Windows). A subtle self-portrait with a cross, the photographer’s reflection straddles the window’s mullion. The bend of her arm echoes the coy gesture of the sculpted recumbent woman displayed between her and the window—between her all-seeing lens and the window’s reflexive blindness. Looking at the image, it’s tempting to imagine this is no shadow at all, but another spectral vestige of this institution’s past.

The date of his appearance to crowds suggests that the photograph was actually taken on June 6.