Continuously reappearing throughout the French version of Jean-Luc Godard’s 1963 film Le Mépris [Contempt], Georges Delerue’s melody Thème de Camille is the epitome of contained tragedy. Composed for a string orchestra, it has a regular, continuous motif traversed by arpeggios in counterpoint. This combination creates an immensely pleasurable (and sad) tune that flows back and forth, like the player’s hand bowing across the cello’s strings; like the calm Mediterranean summer sea waves that surround the Casa Malaparte in Capri, in which the central moments of Le Mépris take place; and like Amie Siegel’s elegant and sharp exhibition “Backstory,” whose interplay of absences and presences pay tribute to a fundamental knot of twentieth-century Western film culture.

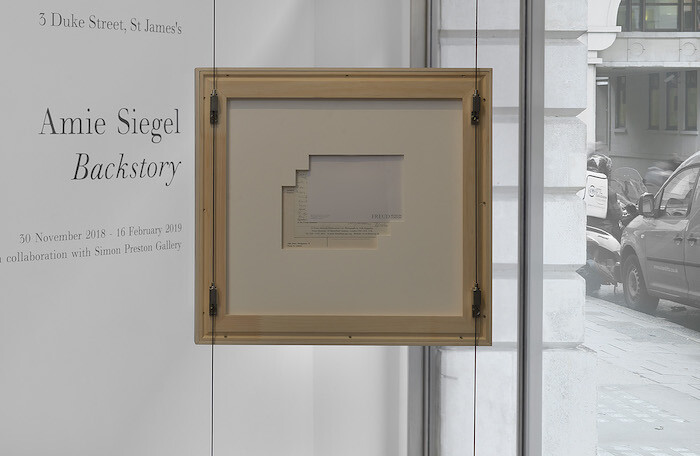

“Backstory” honors its title. Through a set of paper works, “Body Scripts” (2015), and two video installations (Genealogies, 2016, and The Noon Complex, 2016), the exhibition gravitates around Godard’s stunning depiction of the collapse of a marriage between a submissive screenwriter (Michel Piccoli) and his loveless wife (Brigitte Bardot). Remaining close to Siegel’s ongoing inquiry into how value is achieved and generated and her interest in the meta-reflexivity of cultural production, the show brings forward a set of literary, cinematic, and pop-culture references that contextualize and unfold the dense narratives encompassing Le Mépris alongside broader politics and aesthetics of cinema.

But “Backstory” can also read as the backstory of Le Mépris, which Godard was forced to re-edit to include the naked body (and backside) of Brigitte Bardot. To sell better Godard was forced to sell out: the original cut of the film wasn’t profiting enough from Bardot’s iconic figure. As Anne Carson puts it: “When the American producer [Joseph Edward] Levine saw the first cut of Contempt he was irate, felt he’d been cheated, and demanded nudity. He wanted to get his five million francs’ worth out of that body. So Godard added a scene at the start of the film, before the credits. It shows a naked Bardot lying on a bed with her husband beside her. They are talking. She is asking him if he likes her body. She itemizes every body part.”1

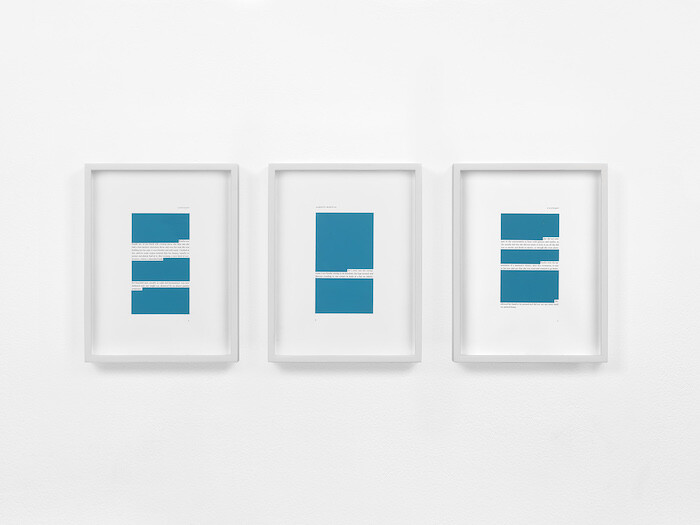

Godard seems obsessed with the double-bind persona of Bardot. He subtly discloses Le Mépris’s backstory in its promotional trailer, in which he calls it, not without irony, “the new traditional film of Jean-Luc Godard.”2 A few films later, Jane Fonda and Yves Montand re-enact Le Mépris’s bed talk in the opening scene of Tout va bien [Everything is Fine] (1972), this time set in an industrial, suburban environment. (Both films brilliantly juxtapose social, affective, and identity polarities in pre- and post-May 1968 France.) Throughout Le Mépris, Bardot ambiguously veils and unveils herself with a thick red towel that wraps her body like a veil on a classical sculpture, further highlighting the economic-emotional-aesthetic-sexual tension surrounding her image. “Body Scripts” explores concealment and disclosure in relation to a woman’s presence in a similar manner. The work consists of a series of framed texts extracted from A Ghost at Noon, the English translation of Alberto Moravia’s 1954 novel Il disprezzo, which, inspired by Homer’s Odyssey, in turn was the basis of Godard’s screenplay for Le Mépris. Where Bardot covered her body with a red cloth, Siegel applied a Tyrrhenian Sea-blue gouache to large sections of the texts, leaving visible only those segments that feature Emilia (the book’s female character, renamed Camille in Le Mépris). Rhythmically arranged, they fill the perimeter of the gallery’s first room: an abstract score in which the cadence of the Mediterranean waves encounters the pace of Thème de Camille.

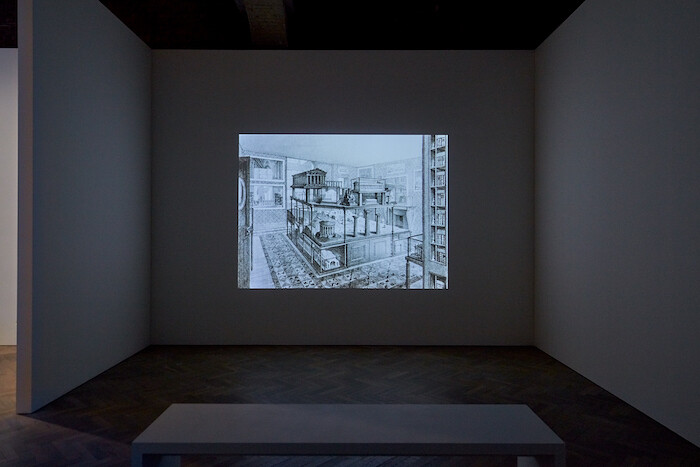

A large projection of Genealogies fills an entire wall of the following room. The video brings together an eclectic profusion of still and moving images—photographic documentation, snippets from films, advertisements, and music videos—weaved together by the artist’s voiceover. Half lecturing, half storytelling, Siegel shares her decentered, non-linear research, where one finding leads to another in a multilayered account that celebrates horizontal, non-hierarchical approaches to visual culture. Potentially a rabbit hole of meta-academic knowledge and highbrow erudition, the work instead inserts itself in the most lucid and generous tradition of artistic research, where Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas (1924–29) meets Ad Reinhardt’s slideshows. In a particularly eclectic moment, Pink Floyd’s Live at Pompeii concert (1972) follows Ingrid Bergman in Roberto Rossellini’s Viaggio in Italia [Journey to Italy] (1954) and precedes a 2012 commercial by Persol paying tribute to Casa Malaparte, named after its original owner, writer Curzio Malaparte.

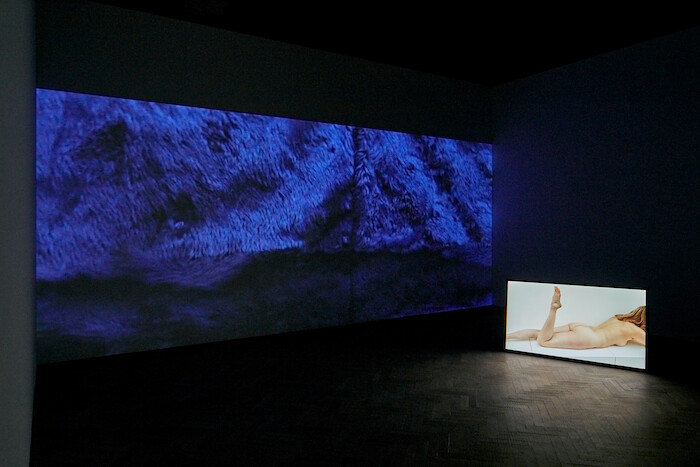

Casa Malaparte is also the set of the multi-channel video installation The Noon Complex, which, like “Body Scripts,” follows a logic of division and subtraction. A large projection features scenes from Le Mépris set in the house, but minus Camille/Bardot, who has been digitally erased from the film. Without her, the camera appears lost, panning around in search of the actress, trying to find the driving force that moves the film forward. At the same time, the house, in its ascetic opulence, becomes a surrogate for Bardot’s attention economics. A flat screen placed on the floor next to this projection shows a white, blonde, middle-aged woman, sometimes dressed, others naked, who replicates Bardot’s gestures and movements in Le Mépris. She’s like a prop that has been placed in front of a green screen, ready to be Chroma-keyed to the original film. Instead, she’s filmed in a large, empty, blue-chip-like gallery, which makes the whole scene uncanny: this new-old figure reifies Bardot’s old-new image in an equation where female bodies are as arbitrarily rendered and substituted as items in a catalogue. With this transposition, it’s unclear how Siegel is surpassing the ambivalence of a gendered body that has been monetized and profited throughout centuries of art, film, and culture’s promiscuous relation to capital. But at that point, Camille, the melody, returns to the room, and with it Bardot’s self-inventory perpetuates this conflict between pleasure and emancipation: “Do you see my feet in the mirror? Do you think they’re pretty? Do you like my ankles? And my knees, too? And my thighs? Do you see my behind in the mirror? Do I have a cute ass? Shall I get on my knees? And my breasts, do you like them? Which do you like better, my breasts, or my nipples? Do you like my shoulders? I don’t think they’re round enough. And my arms? And my face? All of it? My mouth, my eyes, my nose, my ears?”

Anne Carson, “Contempts—A Study of Profit and Nonprofit in Homer, Moravia and Godard” in Float (London: Penguin Random House, 2016), 8.

https://youtu.be/Dqwv9XkHOpk.