This retrospective of the Ndebele painter and unofficial artist laureate of post-Apartheid South Africa presents two origin stories. The first, from which its title derives, tells of how Esther Mahlangu first identified as an artist when, having been reprimanded for daubing the walls of her family home as a child, she persevered until she was good enough to be permitted by her mother to paint its façade. The second, taking place several decades later, arrived when a group of European researchers came to her village to seek out the woman responsible for decorating the house in their photograph. “We want you,” they said, “to come to Paris.”

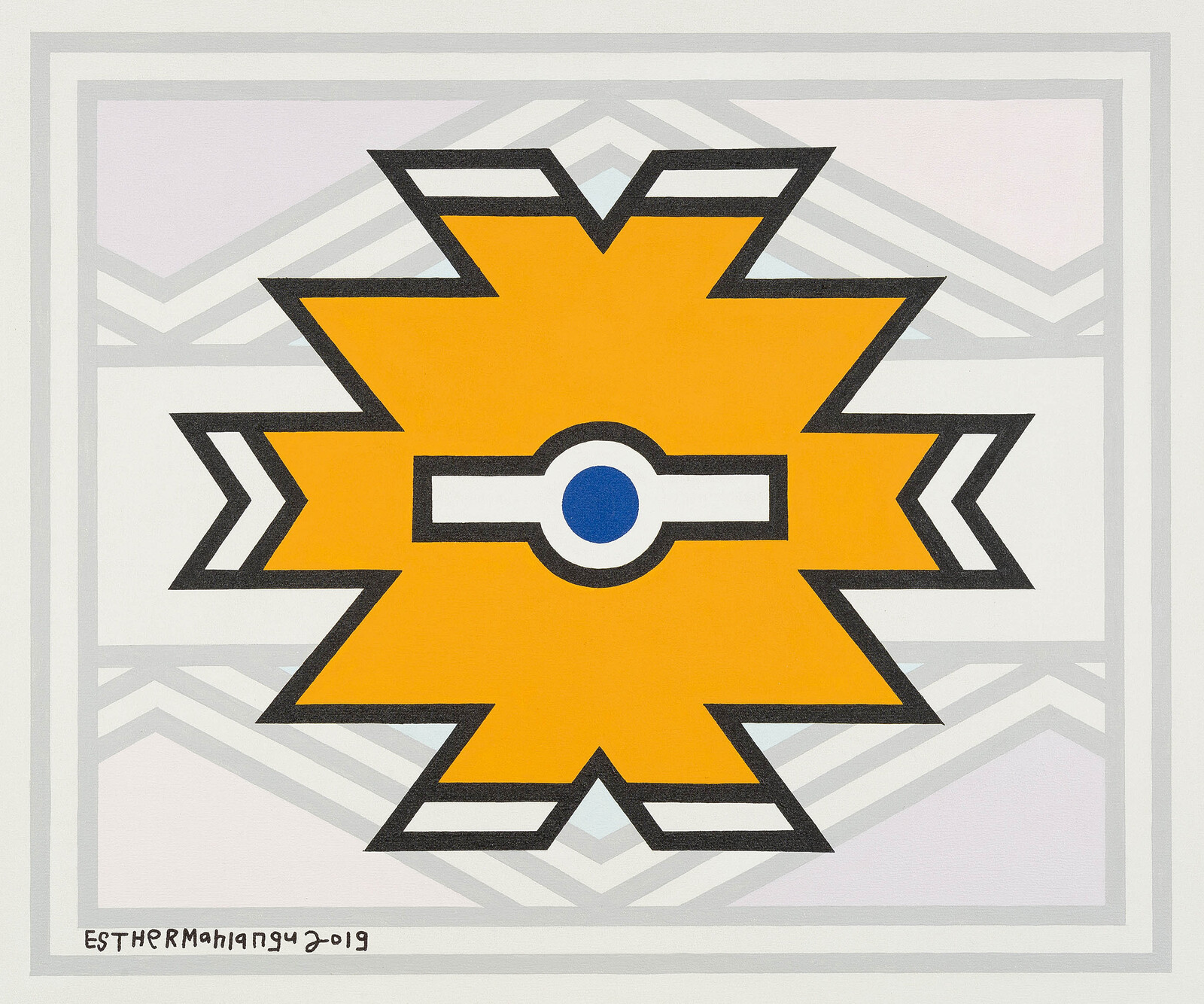

The invitation was to participate in the 1989 exhibition “Magiciens de la Terre” at the Centre Pompidou, a show that continues to cast a long shadow over attempts to decenter or decolonize the representation in western institutions of global visual culture. Mahlangu contributed a reproduction of her own painted Ndebele house (reproduced in miniature in this exhibition), setting in train a career so prolific that her vivid polychromatic designs now serve as visual shorthand for Nelson Mandela’s vision of South Africa as a comparably vibrant and harmonious “rainbow nation.” These instantly recognizable patterns—since applied to objects ranging from television sets to sneakers to the 1991 BMW 525i positioned in the show’s final room—expand a tradition of house painting that started in the late-nineteenth century as a highly coded expression of Ndebele resistance to the incursion of Boer settlers onto their ancestral lands.

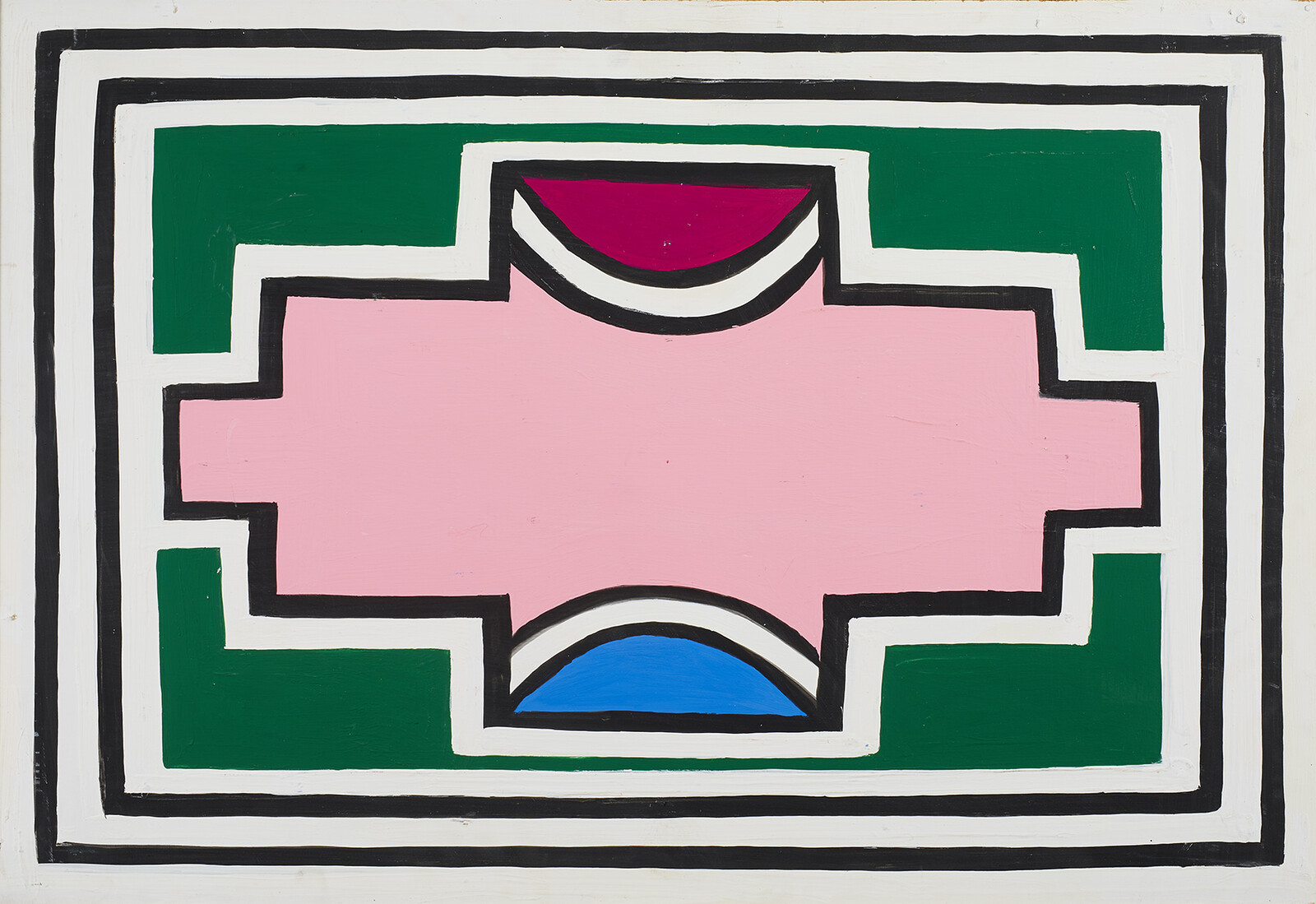

An exhibition that attempts to accommodate these competing narratives of Indigenous craftsperson, national standard-bearer, self-fashioned female artist, modernist painter, and Warholian entrepreneur opens with eighty-seven small canvases hung in a grid on a peach-painted wall, each of them featuring a design in flat, bright colors (one exemplary Ndebele Abstract, 2022, arranges four yellow chevrons on a black ground separated from a repeating pattern of rotating white wedges by the band’s white border). The implication of their positioning is that this might be the visual alphabet out of which the artist constructs the more complex patterns of her larger paintings and murals. But if these forms do carry symbolic meanings, they are not elaborated upon, and the placement in front of the grid of a pair of painted ballroom shoes (Suid Afrika Vorentoe, 2003) confuses any such attempt to read the work through established art historical frameworks, whether ethnographic, formalist, or mass cultural.

It soon becomes clear that the standout works in an exhibition curated by Nontobeko Ntombela do not fit neatly into the narratives for which Mahlangu has often been claimed. The first of these pleasant surprises comes in the exhibition’s second room, with the appearance of an AK47 rendered in Ndebele beadwork and resembling a glittering soft toy. By transforming phallic armament into flaccid ornament, Beaded Rifle (2013) offers an alternative take on the artist as a proponent of “soft power.” The three colorful abstract prints gifted by President Cyril Ramaphosa to world leaders at the 2023 BRICS conference in Durban appear, by comparison, to be harmless.

Similarly, the monumental canvases that most closely coincide in format and medium with western conventions of geometric abstraction can seem lifeless (perhaps because the isolation and magnification of one design from a pattern can seem to orphan it) besides the painted domestic objects, beadworks and textiles, and less familiar figurative paintings. Take for example the exceptional Untitled (Figures with Dwelling) (2007), which depicts a painted Ndebele home as if it were its own bounded cosmological system, or Souvenir de Paris (2003). The Arc de Triomphe and Notre Dame are represented in the latter at the same scale and in the same paintwork as a Ndebele homestead, the two cultures separated—or connected—by a jumbo jet emblazoned in traditional patterns. The work might equally be explained as the inversion of cultural hierarchies via the counter-appropriation by an Indigenous artist of colonial symbols or as an image of peaceful exchange and cultural reciprocation, but the painting is more interesting than such easy interpretations would allow. Rather than serving a rote political function, it suggests an insatiably curious artist with the talent to distill disparate elements through a distinct visual sensibility into an aesthetically coherent whole.

That the Ndebele Abstracts of Mahlangu’s late career might exhibit incidental formal similarities with, for example, hard-edge painting does not necessarily mean they should be read as expressions of an African-inflected modernism. We might instead take them as evidence that intricately constructed and brilliantly colored patterns have always functioned as vehicles of meaning and catalysts of feeling across cultural contexts (Mahlangu’s murals might equally be compared to the design work known as xysta on the Greek island of Chios, for instance). Similarly, people were painting repeating designs onto the surfaces of their household objects long before the invention of Pop. The attempt to situate such traditions within the “high” histories of western art—and thereby, by implication, to elevate it—risks doing both the work and its social contexts a disservice.

Whether or not the exhibition’s category confusion is the curatorial intention—it might also be a symptom of a desire that the work be all things to all people—it is to the work’s advantage. By staging the difficulty of reconciling the idea of the “artist” as validated in a traditional community with the idea of the “artist” as anointed by institutional curators, art historians, or the globalized market, the exhibition might even be more faithfully representative of a country still struggling to build a new society out of antithetical cultural narratives. More broadly, it might also cause visitors to South Africa’s national gallery—wherever they come from—to reflect on what they understand the role of the artist to be in their own society. The best of this uneven but frequently startling survey is a reminder that there are many more varied applications of that vocation than are accounted for by the conventions of art history or institutional exhibition-making.