Nils Staerk is the latest commercial gallery to spring up amidst the coffee shops and organic wine bars in Nordvest, a district of Copenhagen that the local media are more likely to associate with violent crime and unemployment. A further reminder of the uncomfortable coexistence of two worlds stands directly outside the gallery’s doors, in the shape of a mobile shelter for the homeless.

It seems fitting, therefore, that Swedish-Argentinian artist Runo Lagomarsino’s “We Have Been Called Many Names” highlights the invisibility of undocumented migrant workers in the United States. The exhibition consists of an installation of 28 white plaster casts of hats placed on wooden plinths, which occupies most of the gallery’s main room. The hats from which these sculptures have been cast—some made of straw, others the caps worn as part of a uniform—belong to workers in Los Angeles. These cleaners, security guards, gardeners, and service laborers operate on the fringes of American society, with few rights and no voice even as they perform the essential tasks that those from more secure backgrounds might turn their back on.

The array of wooden stools that serve as plinths form a square grid through which visitors can walk and inspect the diverse arrangement of hats, attaching to each a unique story with a shared ending. At the far end of the room Il Quarto Stato [The Fourth Estate ] (2017), a large black-and-white tapestry, hangs from the ceiling. The printed textile reproduces Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo’s famous 1901 painting of the same name, which depicts a group of striking workers, suggesting they constitute the Fourth Estate. Yet the image hangs upside down, a reference to América Invertida [Inverted America] (1943) by Joaquin Torres-García, for which the Uruguayan painter inverted a drawing of South America so that southern hemisphere occupied the top half of the frame, and Uruguay was at the center of the world. Despite these important references, the work is too direct to leave room for anything other than the intended reading, and feels didactic.

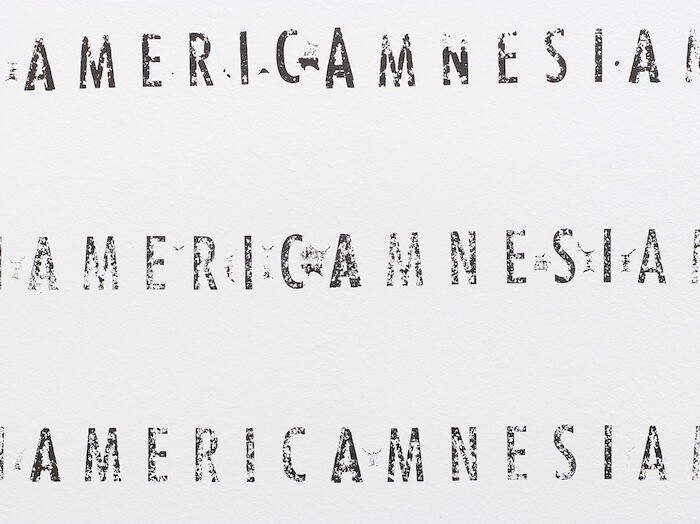

In a second room screened off from the first by the large tapestry, the far wall is covered with lines of text. The word “AMERICAMNESIA” has been hand-stamped directly onto the wall from top to bottom. Variations in the resolution of the lines—some darker, some lighter—make a dizzying spectacle. But the message Lagomarsino is trying to portray is clear, perhaps too clear. On the floor in front of the wall is a stone block in which the imprint of a small hammer is visible, Sorgearbete (2017). The outline is clear, but the tool itself is absent, once again signifying the invisibility of the worker. Where Gustave Courbet portrayed the worker with the hammer in hand (Stonebreakers, 1849), Lagomarsino shows only the hollow imprint of a tool. The two works share the same intention though: to portray the invisible laborers. The English translation of Lagomarsino’s work would be Sorrow Works, and again, the reading cannot be misunderstood.

With “We Have Been Called Many Names,” an artist known for his interest in the legacy of colonial history seeks to draw attention to the lack of laborers’ rights, power, or voice in society. Here, as elsewhere in his oeuvre, he orchestrates simple and carefully selected objects loaded with history in a delicate and yet powerful way. Yet the overall display is a little too easily grasped and feels didactic in its clichéd intentions: carved in stone, and stamped on the wall, it turns things upside down and attempts to bring the invisible to light. The most revealing perspective of the social tensions that Lagomarsino is dealing with is offered by the shelter located just outside the gallery—its juxtaposition reveals a more complex reality than this well-intentioned show is able to resolve.