It’s an unlikely benediction: two identical photos frame Dozie Kanu’s exhibition “Owe Deed, One Deep” at Project Native Informant: a small, slightly blurred image of a tower with a hand at the top, reaching awkwardly towards the sky. Emo State (2020) seems to have been taken from a moving car, the landscape around it giving some sense of the sheer scale of the tower, a religious monument modelled on the tower of Babel in southern Nigeria, constructed only a few years ago and torn down in 2019. The ghost of this demolished structure, the two hands waving over the five sculptural assemblages gathered below them, casts the works as their own temporary monuments, momentary markers to whatever spirit or feeling has possessed us, before disappearing. In a corner, St. Jaded Extinguish (2020) is a gray fire extinguisher stand placed forlornly on a flimsy, short set of black stairs, a bottle opener attached to its base that spells out a nihilistic mantra: “SELF SERVE.”

Making my way around exhibitions for the first time since February, it was such slight, haunted gestures that stuck with me. It feels disconcertingly normal to traipse around the city at this time of year, albeit with pre-booking systems, QR–code press releases, and the incessant taste of my facemask. It is, after all, officially Frieze Week, albeit without the tent, but with a virtual edition and a loose cluster of shows to mark a provisional return to IRL. At the back of a vast room in White Cube’s Bermondsey space, dotted with islands of spotlit plants and fragments of Roman sculptures, burlap cloth bulging with soil and wild flowers, marble feet trailed with nasturtium vines, is an uneasy, chimerical corpse. The truncated torso of a decapitated man, its browned marble surface pockmarked and battered, is propped on top of a square refrigeration unit. Hanging down into the fridge are a pair of mottled black-brown feet, as if mummified, the toenails a polished gold; a small fly and a dead moth keep the cooled flesh company. Beauty Queen (2020) is the full stop at the end of Danh Vo’s “Chicxulub,” a presentation of scattered assemblages of ancient and more recent ephemera, at times casually evocative, at others a facile plonking-together. Putting the feet on the torso gestures towards a Dr. Frankenstein-like attempt to connect and reanimate the stone and bronze body parts, but it feels more like witnessing a death.

In June, on Can Altay’s Ahali podcast,1 curator and theorist Stephen Wright suggested that galleries could use this moment to turn away from the twentieth-century format of the exhibition, putting the energies and adeptness of exhibition-making towards other activities. Precisely what activities he didn’t exactly say, though I’m pretty sure he didn’t mean shaky pans across empty rooms as video tours of shows, or the jpeg blog “viewing rooms” that await online visitors to the Frieze fair website. Much of the work physically on display in the city at the moment, as many of the press releases are keen to inform us, was made during lockdown and isolation. Shelves of objects made each day, lines of drawings and small paintings across walls are recurring set-ups: these are monuments and altars to lost time.

Martine Syms’s three-screen video installation Ugly Plymouths (2020) at Sadie Coles HQ is a barrage of smartphone footage that feels like a fragmentary lockdown diary. Snippets of footage from concerts, fashion shows, strip bars, and holiday destinations feel like they’re being wistfully scrolled through, while three narrators occasionally chime in, exposing the reality of wanting, and failing, to meet up. “What are you up to tonight? When are we going to go on a hot date?” We see shots of people singing, a hippo swimming; at one point all three screens show a nighttime firework display, peppered throughout with moments of the artist mid-video call. Within the dense confusion is an concise portrait of the intention, isolation, distraction, and disjuncture of this clusterfuck year, where even when you’re stuck at home, everything cancelled, the sentiment is still, as one character yells: “I don’t mean to be elusive, I’ve just been really fuckin’ busy the past few weeks, few years!”

At Modern Art, a set of small shelves jut into the gallery rooms, each bearing a tiny sculpture of metal, paper, and wood, hastily assembled twists and shapes. It’d be insulting to call them maquettes, as they more than hold their own, but you can sense the precarity and speed behind this minuscule body of work by Richard Tuttle. You Can’t You Have to Buck Up (2019) is a small metal circle, a short band of black drawn on the top, pushed into a wadge of gray putty; Brother (2019) is a sail made of wire, an accordion of white paper zig-zagging across it, held up by a thimble-like wedge of amber-colored resin. Even though made last year, the activity of creating these slight objects feels like a way to mark the days passing.

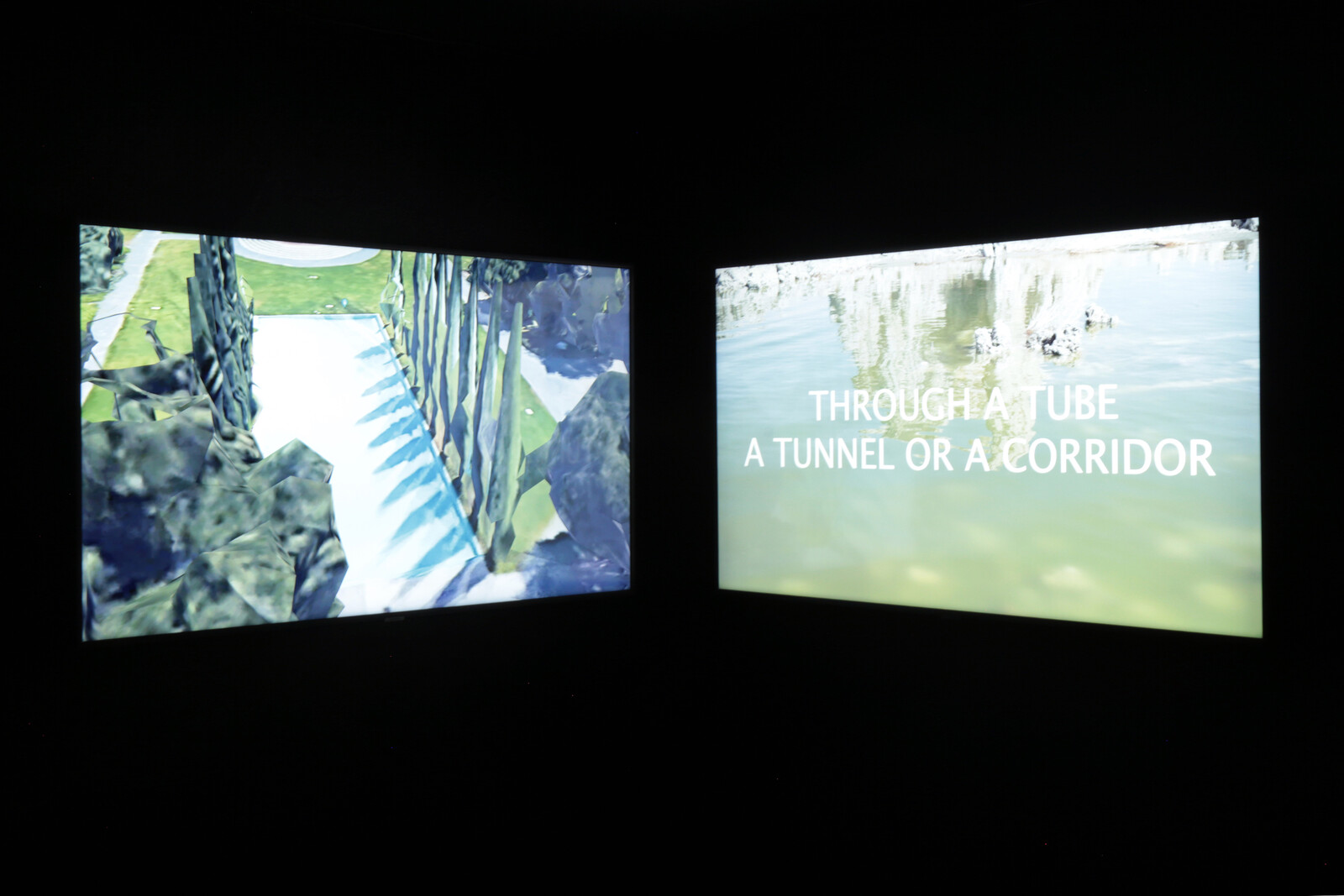

All the Zoom chats and online screenings have, as might already be apparent, made me susceptible to the allure of bald physicality, to sculptural and visceral gestures. At Deptford’s Castor gallery, in a room painted a pale hospital yellow, is a set of Grace Woodcock’s pinkish bacterial blobs made up of silicone and imitation suede. Bolus (2020) is an oval of layered smokey Perspex, interspersed with undulating shapes of suedette that fade into the reflective plastic like rocks disappearing into muddy water. It feels topographical, but also, as the title hints, stands as an elegant reminder that all things turn to shit. Down the road, Solveig Settemsdal’s OK SWALLOW GREAT (2020) is a two-channel video displayed as part of a two-person show with Andrew Sunderland at Gossamer Fog. The screens are set against each other in a corner, depicting on one side what looks like a water filtration plant and a set of luxury swimming pools, and on the other a murky hot water spring, the rocks crusted in limescale and salts. The two videos are unsynched, running in various overlapping configurations over eight minutes, the combined images and text together offering a short meditation on touch and asking “where do we meet.” “We overlap, like this,” words declare across one screen, as water laps gently at a craggy rock that just barely breaks the surface. On the adjacent screen, a swimming pool’s blue-tinted surface fizzes with hundreds of tiny ripples. As the text states, “This surface, it’s so far away in time and space it might as well be virtual.” Settemsdal’s short video has an alluring balance of close, obsessive looking with a disaffected, humorous shrug, suggesting that notwithstanding any philosophical wrangling, we’ll just end up back in a primordial soup.

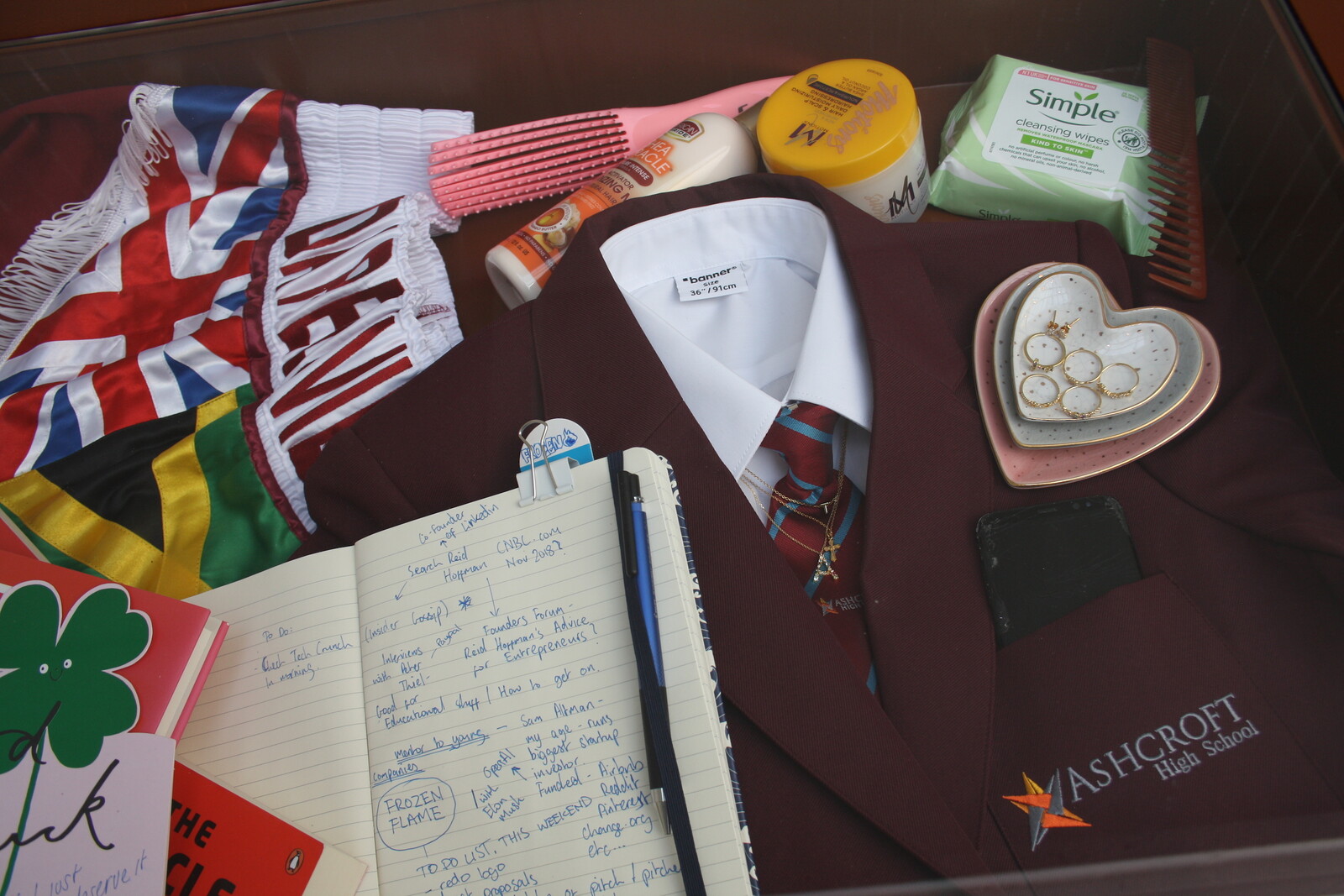

At Cubitt is a small library, a busted-up door, a tree-trunk dangling from a thick chain, and a table for playing dominoes. R.I.P. Germain has set up the gallery as “Dead Yard,” a site for four memorials to people in the artist’s life. In a glass case embedded within the table are a pile of DVDs, Arsenal football shorts, a unicorn cat stuffed toy, and an open notebook, revealing plans to form a startup tech business. Underneath the table, a set of speakers play interviews with men and women speaking about their lives and aspirations. “Perfection is a destructive idea,” one woman states. “What does perfect even mean?” Among these mementos and dreams, among impossibly personal details and stolen moments, the drive here doesn’t seem so much about making discrete artworks for contemplation, but as creating sites for gathering around, activities to move with. Acting as librarian, archivist, and host, Germain suggests that how we remember and how we pay tribute to the past is by learning, by talking, by playing. The world is outside, moving as it may; the exhibition form still seems to have value, sentimental it may be, to mark time, to hold it for a slight moment so that there’s something to remember.