Marcel Duchamp almost had a career as a librarian. In November 1912, having given up on painting for the first time, Duchamp enrolled in library school. Soon, he started work as an intern at the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, where he read about perspective and made notes for what would become The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915–23, often referred to as The Large Glass). His period as a librarian was a crucial moment of transition: just as he abandoned art for books, he would end up dematerializing the art object, realizing that the notes he was taking might be more interesting than the work they putatively described. The Large Glass, ostensibly the end-stage of this part of his career, is ultimately less generative than The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Green Box) (1934), the suspiciously library-like set of notes that might combine, if assembled the right way, to make The Large Glass—or something else entirely.

A book can be seen as a node in a web of potential relationships—between author and reader, books past and future, even seller and consumer—modulated by the ecosystems around them which make such connections happen. The library is tailor-made for relational aesthetics, as Heman Chong and Renée Staal’s itinerant Library of Unread Books (2016–ongoing), currently instantiated as part of the 2022 Singapore Biennale, clearly demonstrates.1 The library’s disinterested motives differ from those driving the world of commerce: a library serves readers; but it also serves others; it might, for example, give an artist an easy job. A library preserves information; at the same time, it might confer distinction on an institution. Crucially for Duchamp, in a library the importance of the network to the work becomes apparent. A book changes when it is shelved next to another; a reader in a library can move back and forth at will between disparate books, creating new connections. A library is a site, above all, of potential: potential connections, potential artworks, that might be made. Of course, a library will contain as many bad books as good ones, and require infrastructure to navigate: Borges’s library that contained absolutely everything would be singularly useless, as Jonathan Basile’s online instantiation proves.2

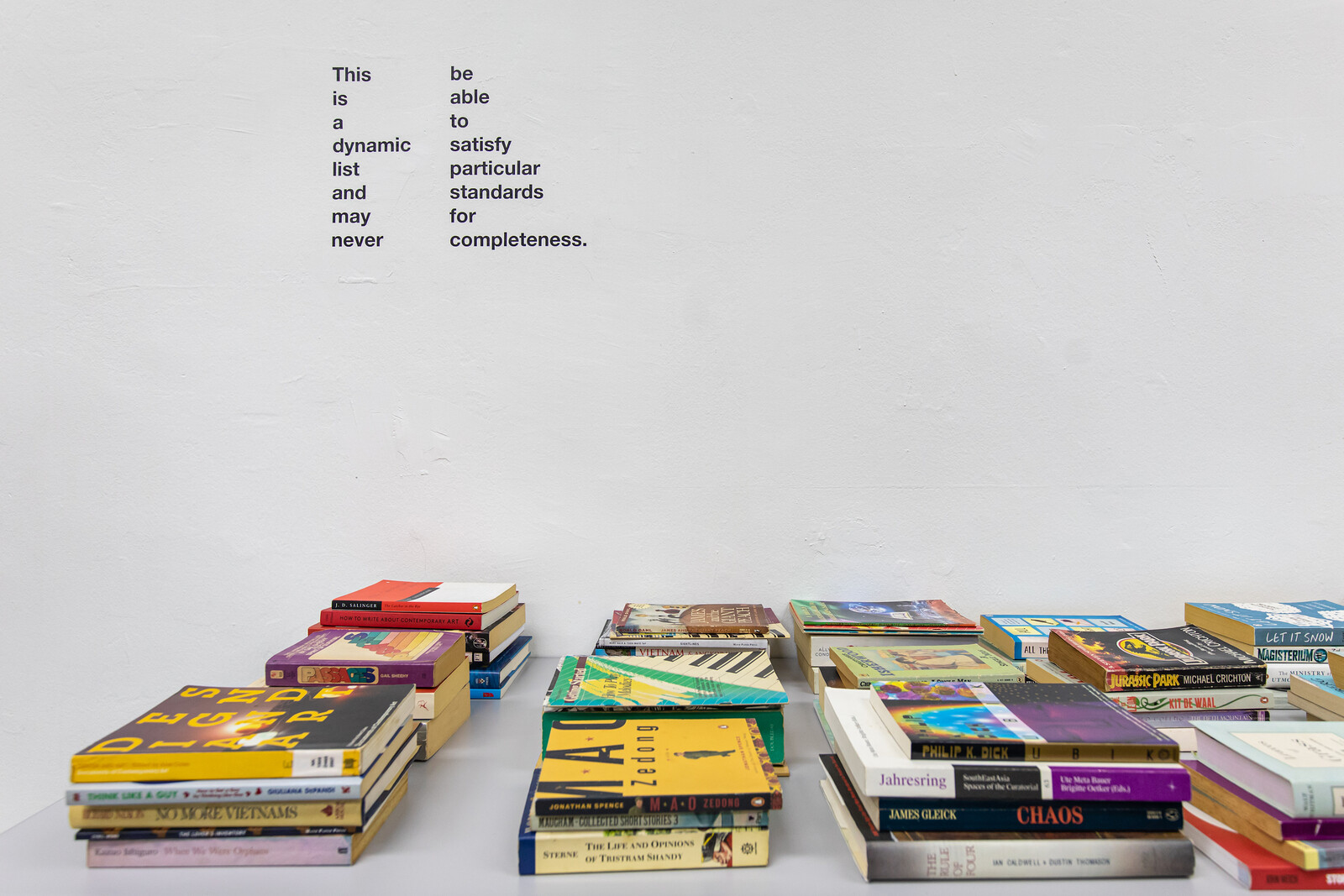

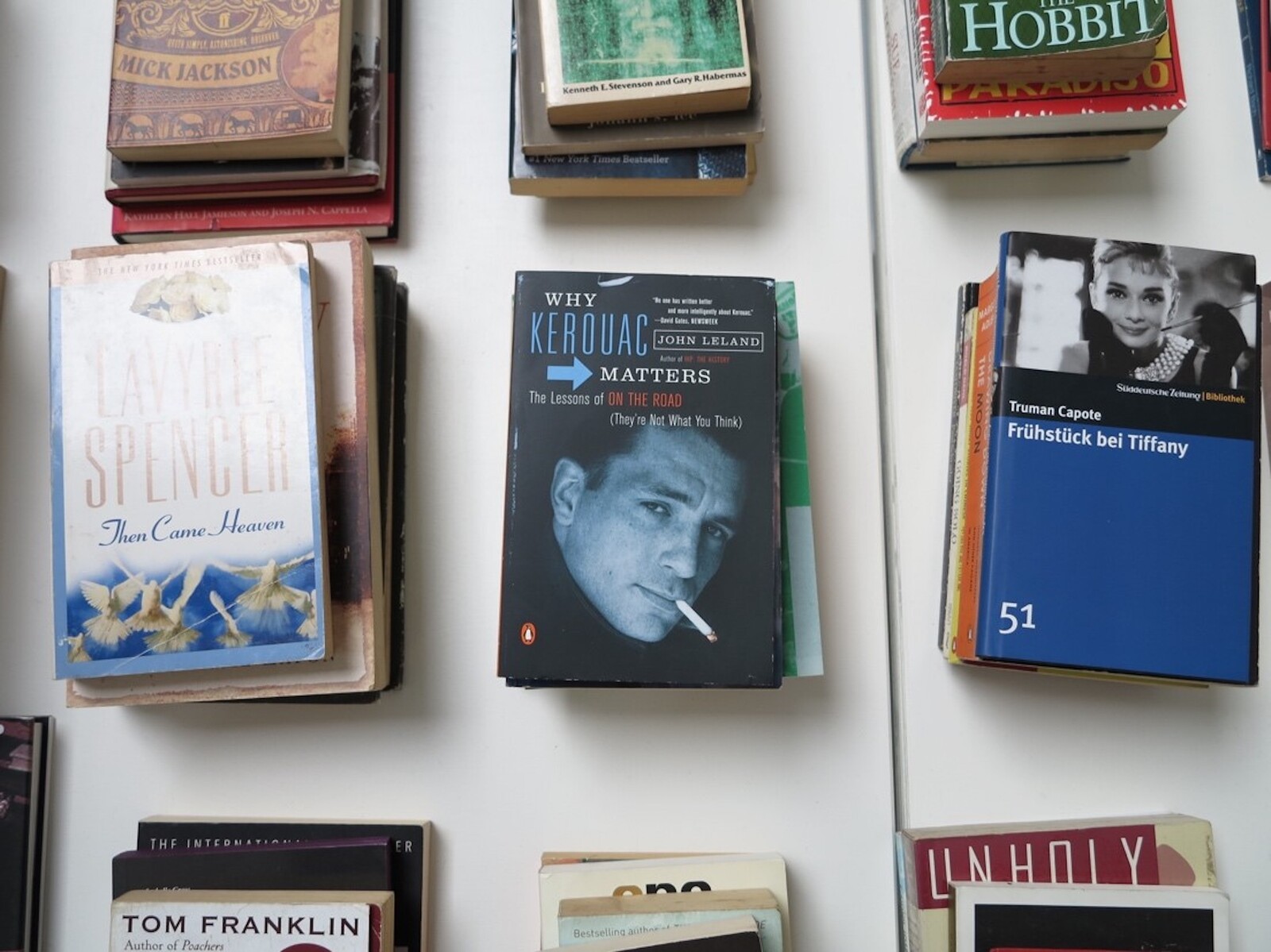

This is the ground on which Chong (the artist) and Renée Staal (the librarian) have built their library. Set to wander around the world for a decade before entering a museum collection, it consists of stacks of books donated by visitors on the condition that they have not been read. It’s presently on show in Singapore in a small room on the ground floor of International Plaza, a nondescript office building not far from the city’s main cargo port. Around the library are food stalls full of office workers getting lunch. Visitors are invited to browse the books. Inside the front cover, a stamp announces the book as part of the Library of Unread Books; the donor’s name is written as well. Donating books is encouraged. Browsing reveals the ambiguous quality of the library: how much does one have to browse in order to convert an unread book to a read one? (Some of these books, one can tell by the spine, would seem to have been read by someone before their donation.)

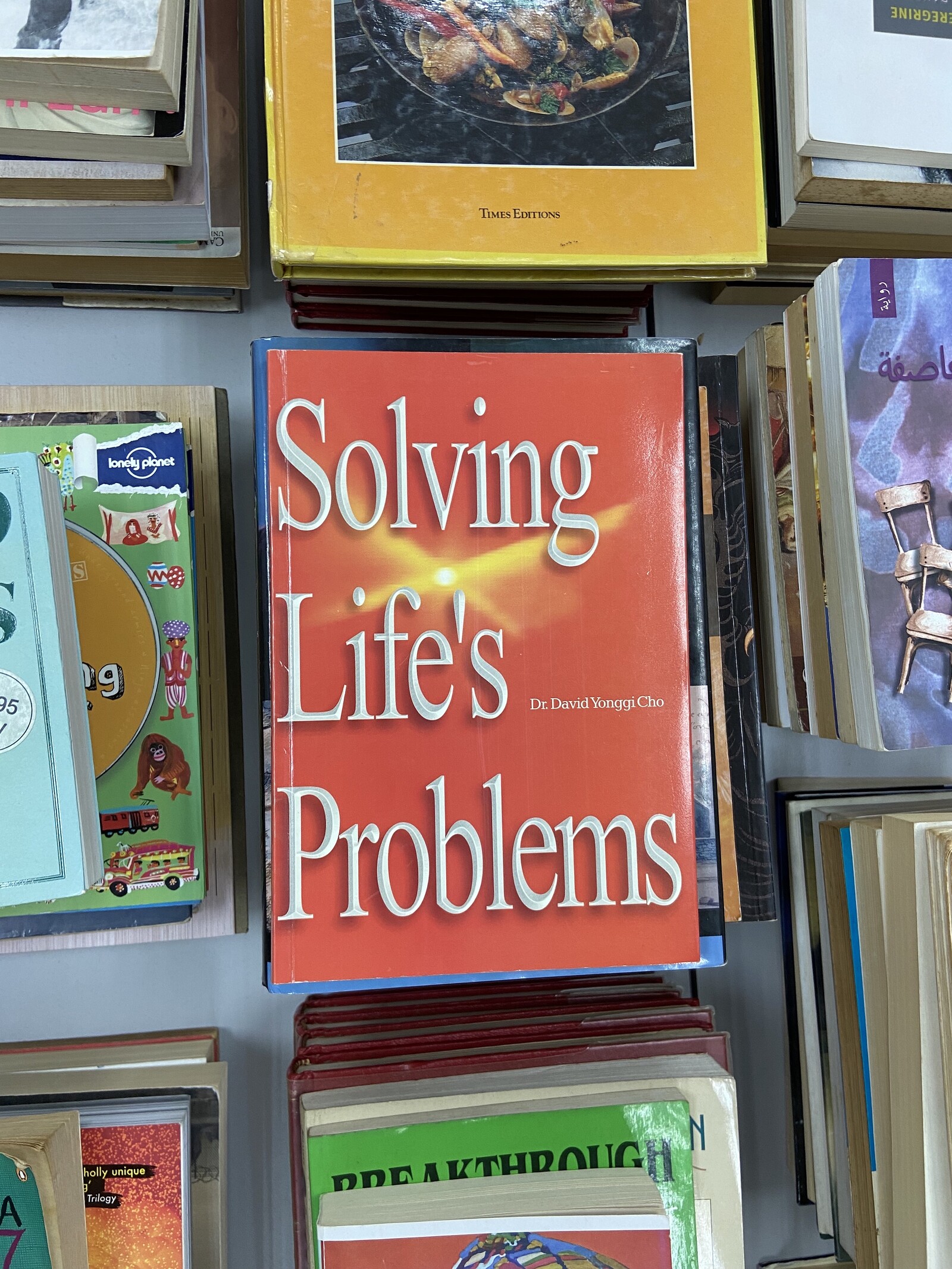

What qualifies a book as an unread book? There’s a difference between a book as concept and any particular copy of it: one assumes that someone, if only the author, would have to read a book to publish it, though this might seem quaint in the age of Chat GPT, where books can be created in vast numbers without a writer involved, much less a reader. Many of the books stacked in the Library of Unread Books seem undistinctive: Twilight novels, Windows 98 for Dummies, Jack Welch’s autobiography—books which might help someone through a computing crisis, or entertain them on a journey, make for a thoughtful gift. But by virtue of being here, these books have presumably not been allowed to act on the world in the ways in which they were intended. This is cause for more consternation in some cases than others: spotting an almost new copy of The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965), a book that might conceivably change someone’s worldview, I can’t help wonder how it ended up here. Maybe it was a duplicate in a well-stocked library; maybe someone decided they didn’t care.

There’s something missing in this analysis: the database of the library, the invisible armature that structures it. These books are not special: a used book, even an unread one, is generally worth less than the equivalent amount of blank paper. The copies in this library, however, are pedigreed: the librarian knows how the book came into the library, who previously owned the book, where the book came from, where it has been. Value is accrued by inserting the copy into a network, making its connections slightly more visible. These connections stretch outside of the physical library, wherever it may happen to be. The donor is given a library card, with their name, an “index number,” and a date. This scrap of paper is also part of the work: the library extending its tendrils out into the world through the network of people connected to it.

A paper library card might seem passé, especially in Singapore where functional wallets are scarce: phones pay for everything, and apps check out books from the national library system without the intercession of a librarian. At a moment when one starts wondering about the prospect of drowning in a flood of AI-generated content, however, the human scale—and human connections—of the Library of Unread Books might be read differently. Seen through the plate glass doors, the piles of books might look like trash. No one needs stuff anymore. But not all trash is the same. Duchamp’s focus on connection elevates the bits of trash that make up the Green Box into something bigger. Likewise, Chong and Staal call for a heightened awareness of how the book functions in our lives, even when unread.

Open until 19 March: https://www.singaporebiennale.org/.

See Jonathan Basile’s online Library of Babel project at https://libraryofbabel.info.