Though she is best known today for her poetry, Bernadette Mayer’s 1972 exhibition of her durational writing-and-photography project Memory at 98 Greene Street in New York was highly influential: the young Kathy Acker, for one, began a feverish correspondence with her after her immersion in its images and voice. In a journal entry around the same time, Acker wrote that she admired “B. Mayer’s work list of daily events facts,” commenting that “I feel her work touches reality I distrust my own.”1 Acker, a post-punk appropriationist who devoured classical literature for the creation of her own twisted myths, may have longed for reality, but never for realism. Similarly, Mayer’s genre-busting work was a diary that never settled for the purely diaristic.

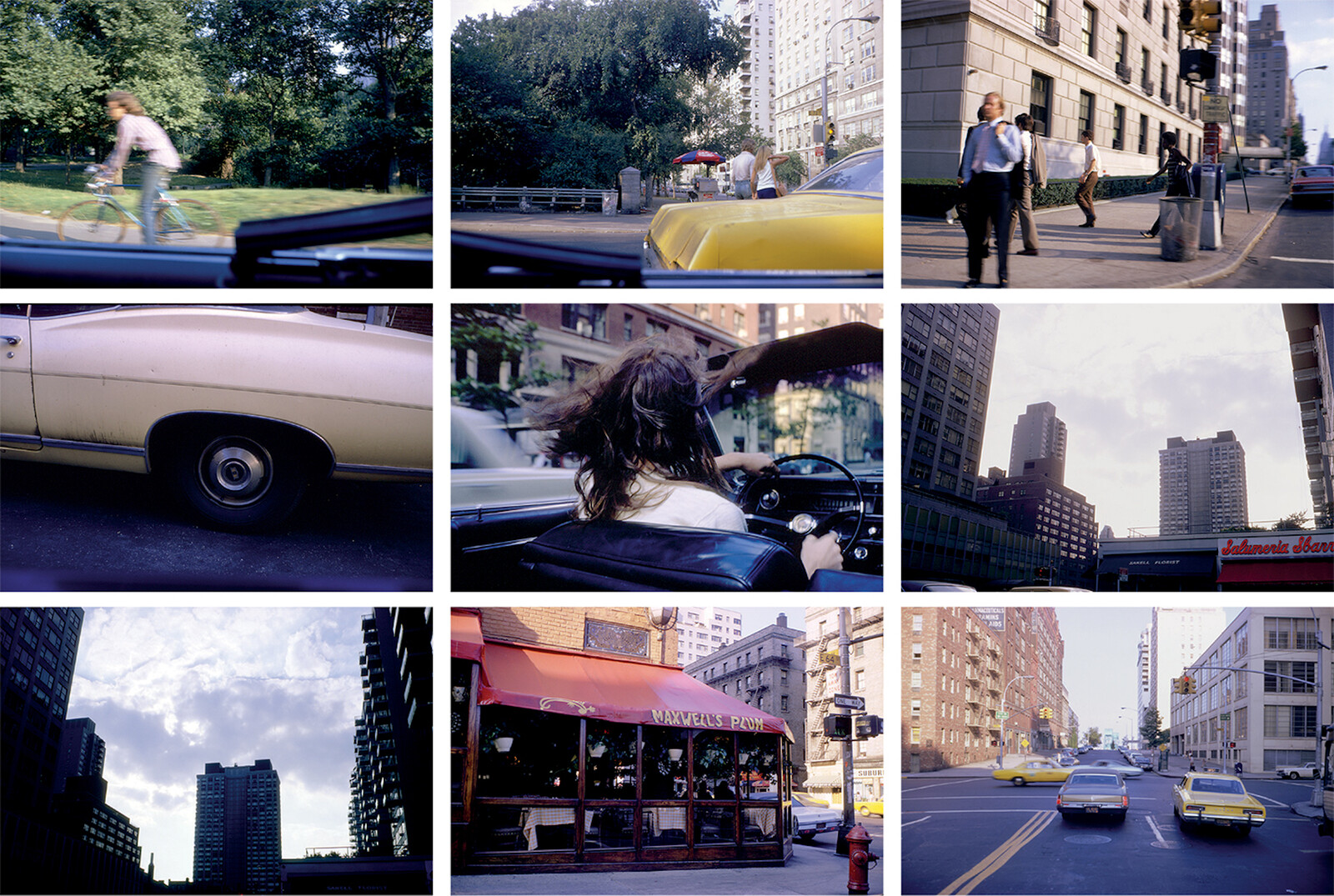

For the month of July 1971, the 26-year-old poet kept a stream-of-consciousness journal and shot a roll of 35mm Kodachrome slide film every day. When the month was up, she projected the slides and supplemented her original observations with new details taken from the images—casual scenes of everyday life, from her lover in the driver’s seat of a car to nature walks and late-night chats with fellow artists. Memory, the completed work, comprised a grid of 1,116 photographs produced from the slides, and a six-hour recording of Mayer’s words. Village Voice critic A. D. Coleman wrote that the piece “explores photography not as art but as a tool which has extended our vision in ways we have yet to comprehend.”2 Although Mayer published the Memory text in 1975, her installation wasn’t exhibited again in its original form until 2017 at CANADA gallery, New York, where the work found a new audience interested in avant-garde first-person narrative. I was among them. I remember mostly Mayer’s lulling voice, and the images showing a downtown Manhattan emptied of people—a state that three years ago was nearly impossible to imagine, but now seems like an eerie harbinger of the current moment.

Siglio Press’s new printed edition of Memory includes sumptuous scans of 1,153 slides, printed as grids or as full-bleed images. (Some of the original slides have been lost; others which weren’t shown in either iteration of the exhibition due to over- or underexposure are included here.) Writing at the pace of life, sometimes through the haze of booze or hash, Mayer captures the sensibility of the early 1970s—part hippie, part intellectual, part ennui. Major events, such as the agitation that precipitated the Attica prison riots, are subordinated to the ebb and flow of Mayer’s own life, as she and her partner, Ed Bowes, travel between New York and Western Massachusetts to work on a film project. My copy of Memory arrived as Covid-19 social distancing took effect, when New York itself became mostly a picture seen through a pane of apartment window glass. In the uncertain days that followed I slowed my reading pace to real time, one or two daily entries at a go. I felt the hiccupping momentum of Mayer’s run-on sentences and casual capitalization, the passages of free-association wordplay, and her lists of shitty meals or all the people (first names only, some now famous) she saw in a given day. Mayer’s project emerged at the apex of the Conceptual art movement, in which she was active as a writer and co-editor (with Vito Acconci) of the late 1960s art and poetry journal 0 TO 9; like the works of the related L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E group, Mayer’s writing is invested in the process of conveying information without imposing narrative cohesion. Her rapid-fire nature of translating thought and speech into writing often telegraphs the cadence of internet-speak. A passage from July 1 is particularly apt: “pretending 2 b a normal person spending my time looking at / projections of weeks ago, what was downstairs, were they the same / they’ve found me out i’m in here i’ve exploded some.”

On Independence Day, Mayer begins her daily entry with a list of photo development chemicals, and concludes with images of fireworks. These intricate details of the physical processing of film remind us that, despite Memory’s studied insouciance, image production then had a different value—and a different politics—than it does today. While Kodachrome slide film achieved mass popularity in the seventies, it still required a twelve-step development procedure far removed from today’s economy of instant shareability. Mayer also visited the World Trade Center site, then under construction, remarking that “the most interesting thing about the wtc was the rust on all of the materials.” Her pictures of rubble nod to Robert Smithson’s concept of “ruins in reverse,”3 but looking at them today, they recall the towers’ destruction and the subsequent War on Terror. Likewise, her fantasies which mimic the city-dwelling artist’s desire for space and a slower pace of life are thrown into new relief during the present pandemic: “there’s a house in maine for ten thousand dollars, we’ll get a grant, we’ll think of the mystery of the renovated barn, a house is for, a, protection and, b, insulation.”

Memory is a precursor to the way digital photography operates now, as a continuous record of living. (Mayer even sneaks in an occasional, awkward mirror selfie.) Yet in contrast to many contemporary social media users, she denies the importance of intertwining biography and emotions with history. In her intensive chronicling of her life, most of the language is descriptive, object-like. From this emotional distance, she searches for an audience, much as we shout into the electronic void. Of unanswered letters to her partner, she writes a perfect proto-tweet at exactly 140 characters: “I must make myself known I think maybe my idea of continuing like perfection is to have a person at a distance to direct my flow of words at.” Like Acker, and like ourselves, she seeks satisfaction in a performance of self for an unspecified audience.

Chris Kraus, After Kathy Acker, excerpt republished in Lenny Letter, May 20, 2017: https://www.lennyletter.com/story/lit-thursday-read-an-excerpt-from-chris-krauss-new-book.

A. D. Coleman, “Latent Image,” in Village Voice, February 17, 1972.

Robert Smithson, “The Monuments of Passaic,” Artforum, December 1967, 52–57