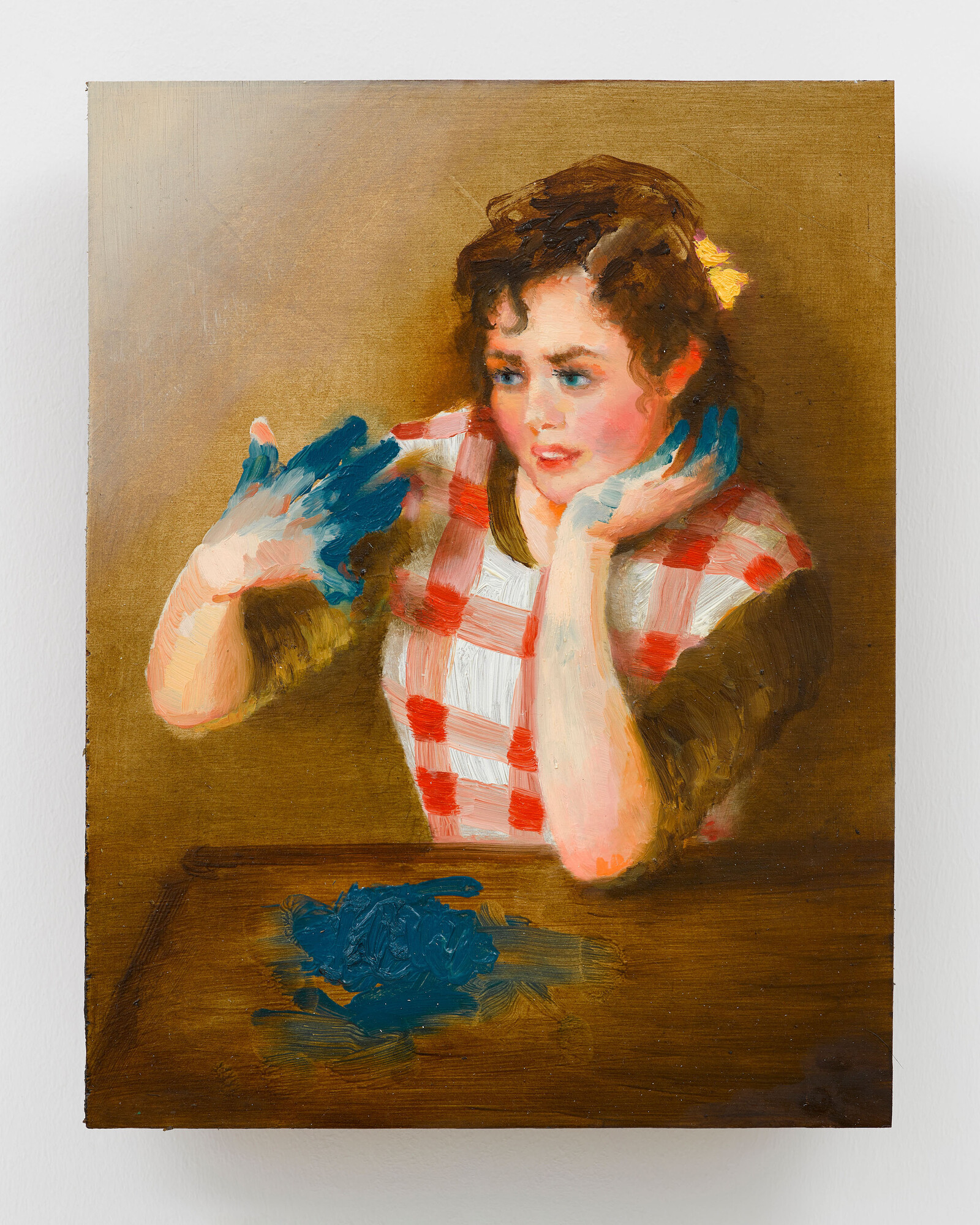

Tursic & Mille’s Blue Monday (January) (all works 2021), an oil painting on a wood panel, depicts a young woman in a gingham dress sitting at a table. She is staring with confused disgust at her fingers, covered in the blue paint that lies, in a viscous blob, on the surface in front of her. Or rather, on the surface of the wood panel. Or rather: both on the table and on the panel at the same time, for the blue is so thickly applied that, disrupting the illusion, it reminds us that a painting is always matter and representation at once. Like this girl, Tursic & Mille are transfixed by this fundamental fact about painting: a fact and a fixation, which seems to unsettle as much as it captivates.

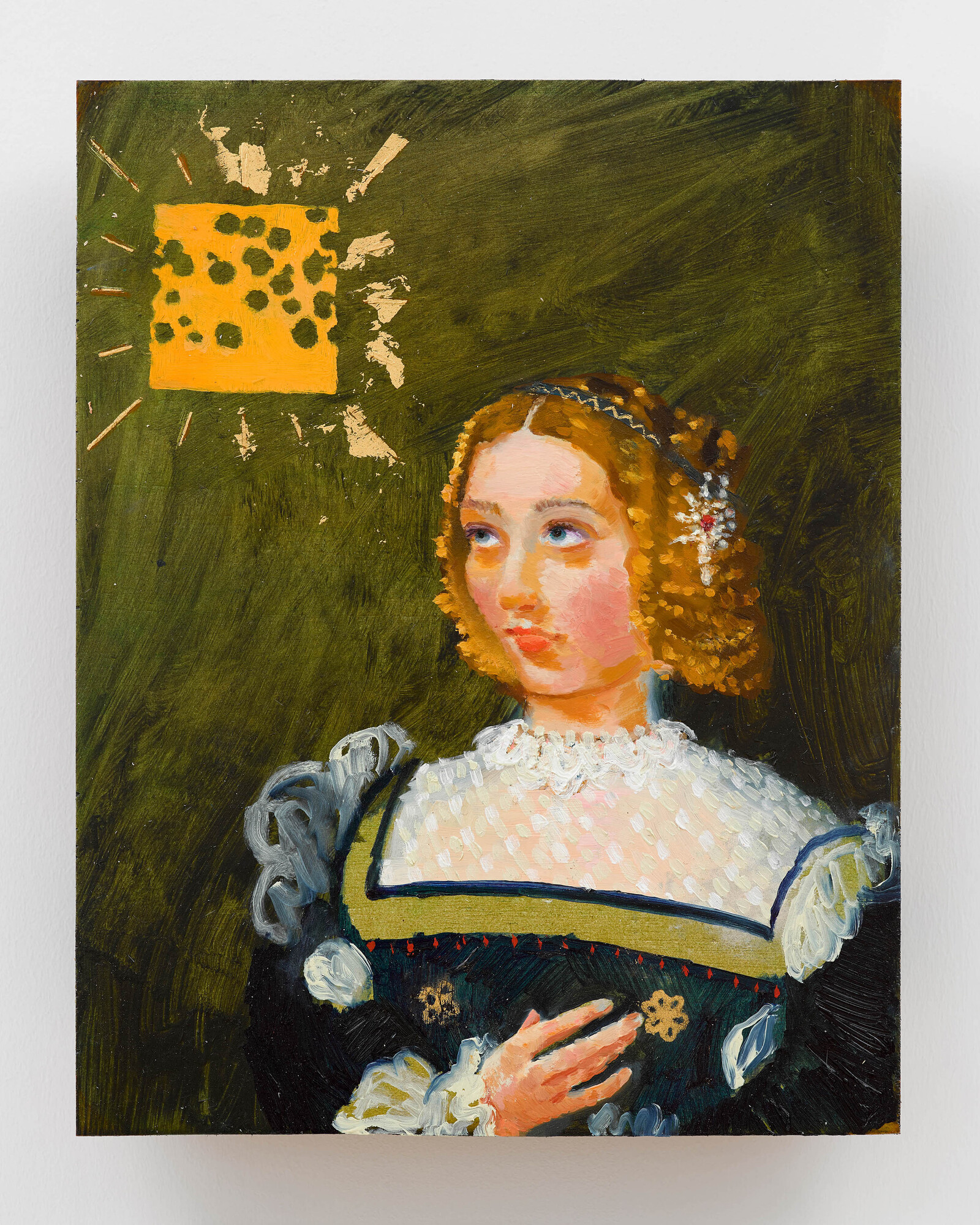

Each painting in “Strange Days,” Tursic & Mille’s first UK solo show, has a month of the year as a subtitle. These works, along with two sculptures of painted dogs, were all painted in 2021, yet the calendar they constitute serves as a summary of the concerns that the Serbian artist Ida Tursic and the French Wilfried Mille have explored since beginning to work together in the early 2000s. They start the year marshalling mocking allusions to the history of European painting: from the defacings of Asger Jorn, who they often cite as a influence, in The Lovely Painting (February), back to the devotional icons and gold leaf in L’intrigante Cosa Emmental (March).

In the summer months we see their other sustaining preoccupation: the world and cultures of internet imagery. Still Life - Interview May 1998 p91 (May), looks back to the print-based celebrity iconography of blond movie stars that the internet continues and supersedes. Juliette la Pharmacienne (July) presents an image from the internet’s unprecedented generation of pornography and one of its many aesthetics: the fantasy of the homemade image-next-door, whose dominance continues in video with the rise of OnlyFans. Unlike in the 2019 Centre Pompidou show which saw them nominated for the Prix Marcel Duchamp, the images here only show naked women, adding to a queasy sense that recirculating such images—of what provenance?—engenders complicity under virtue of critique.

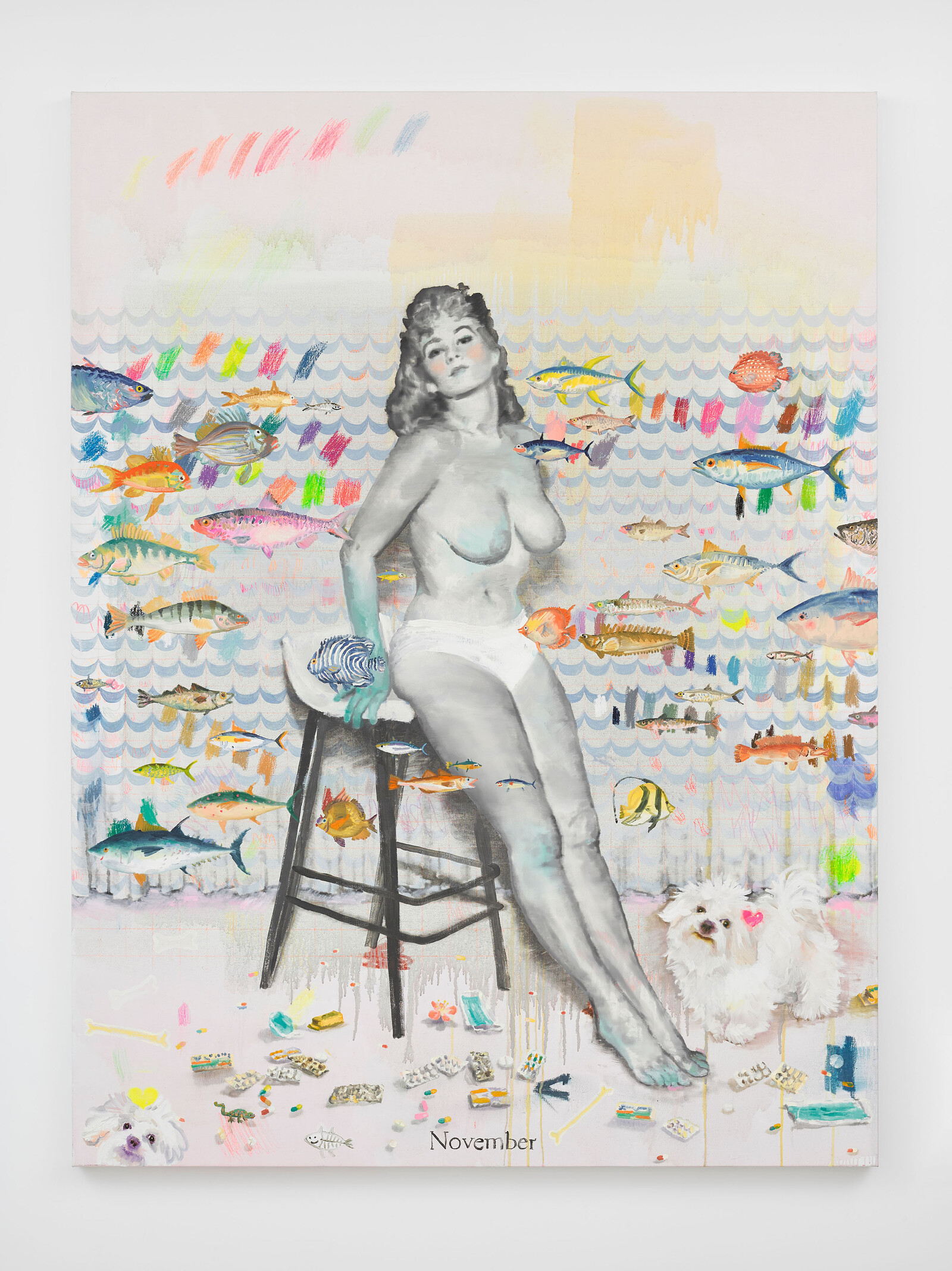

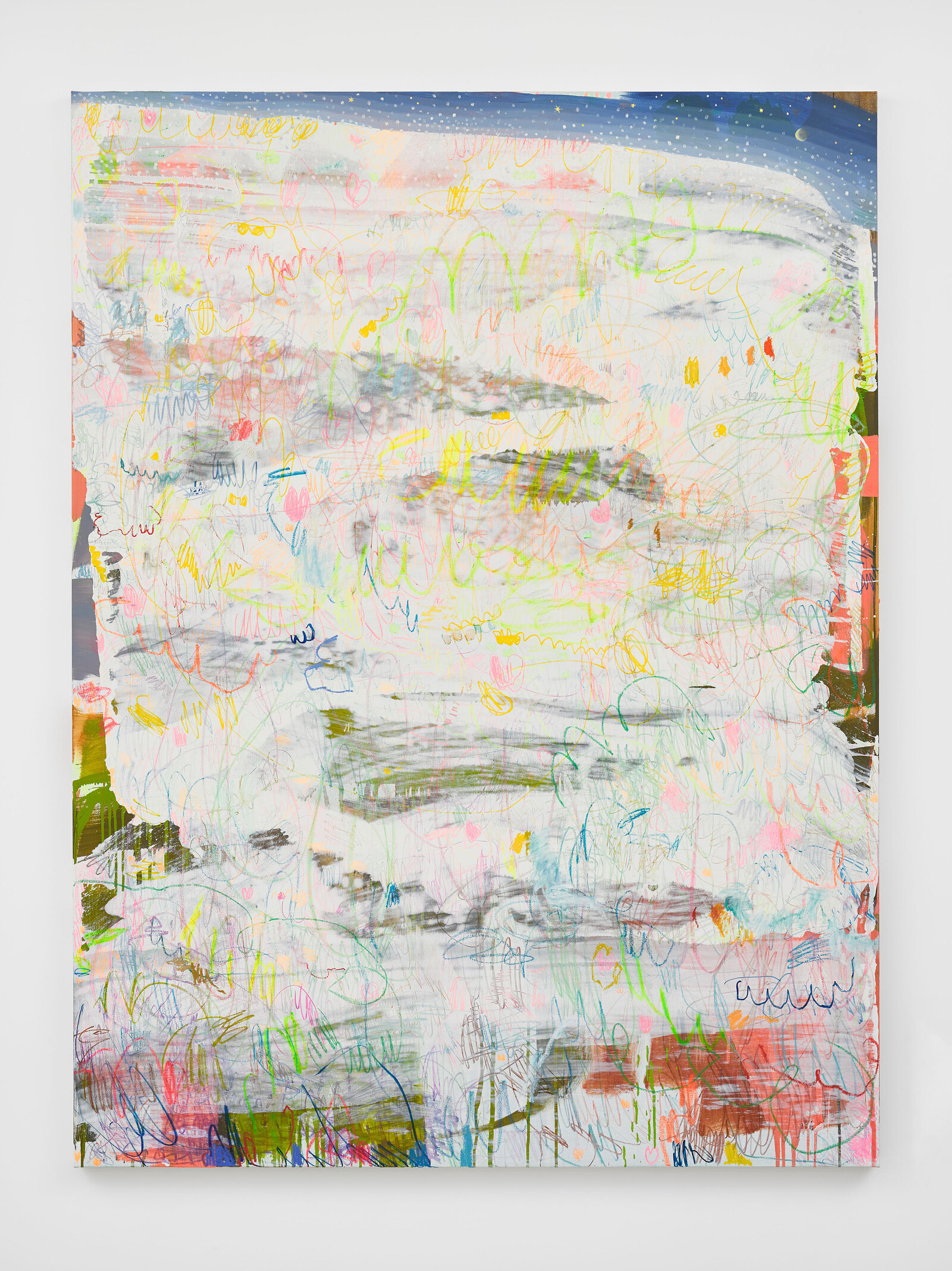

From autumn into winter, their work largely goes back through the iconographies of previous mass media systems and the work of earlier artists who grappled with painting’s relationship to the imagery they release. In Happiness and Clouds (August), the housewives of 1950s magazines float among fields of abstract color: a technique that, for Clement Greenberg, supposedly secured painting’s autonomy against this debased world of kitsch. Fish & Faith (L’Attente) (November) presents a black-and-white image of a woman in underwear, painted in a pastiche of Gerhard Richter’s trademark blurring of photographic source material. It is a move, like many of their allusions, that comes across as knowing, pre-empting. We know questioning painting’s relationship to media imagery isn’t original, we are too smart to aim for originality. All well and good, but what does it serve other than a demonstration of knowledge and the comfortable inhabiting of irony? Like many artists who use painting as a medium to engage with digital imagery, Tursic & Mille appear overwhelmed by its profusion, rather than able to offer, through the manipulation of color on a surface, insights into its effects, attractions, pleasures, or dangers.

In an accompanying introductory text, Tursic & Mille say the question that guides their work is “what is a painting?” Yet the exhibition’s cycle through a year suggests a different way into the vexed question of painting’s role in a digital age: when is a painting? Digital images exist in motion: they can always been manipulated by software, they constantly circulate across platforms. Paintings too, as the heroine of Blue Monday shows, come into being only when liquid becomes solid, when gesture leaves a trace. The fact that painting is a process suggests an ability to mimic techniques of image manipulation, or to document the styles of images whose existence depends on the fragile preservation of digital code. Yet in awe of their material and ashamed of their medium, Tursic & Mille appear, in the end, like the dogs that stand around the gallery: cute, inoffensive, staring blankly at the images around them.