A friend once called me out for overusing “the viewer” in my writing. “What does this viewer stand for?” he asked, suggesting that to use an abstract generality as a stand-in for the self absolves the writer of having to account for their own presence. Initially I saw this as a comment about the politics of being a body in space; that viewers are not interchangeable, experiences matter, and they are distinct. This conversation convinced me that the personal can be a powerful position from which to reflect.

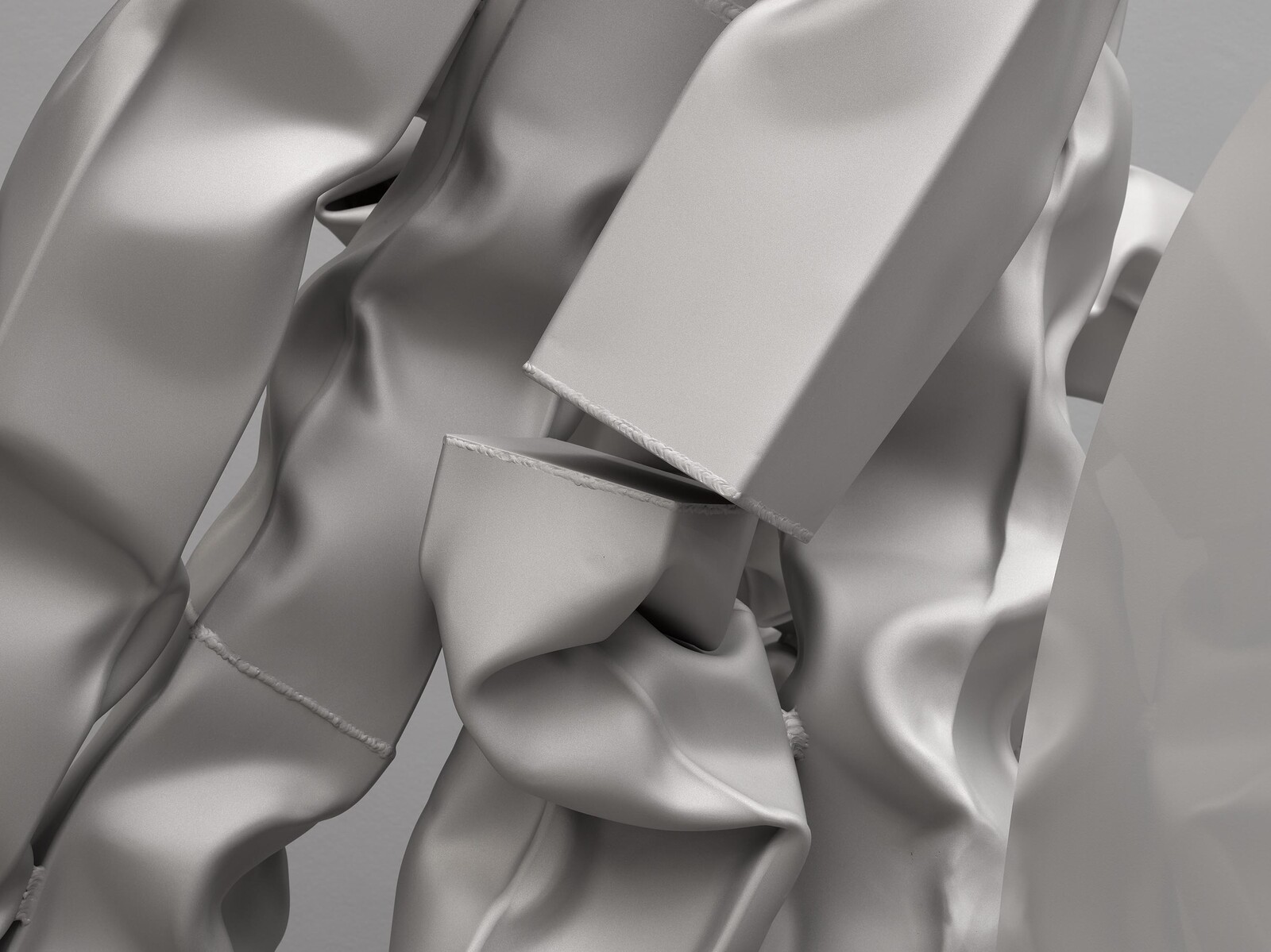

So, here goes: I stood in front of Carol Bove’s new sculptures at David Zwirner and related to them in a way that is intuitive and emotional, a way that made a specific viewer of me, one whose life seeps into the looking. Though they’re made of metal, I saw their softness. I kept staring at the meeting points of two bits of steel, and found in them a connection. Bove’s exhibition, “Vase/Face,” includes two sets of works presented across two rooms, two presentations that differ in scale, color, and treatment. In the main space are four large-scale sculptures made of stainless steel and laminated glass with heat-fused ink. The sandblasted stainless steel registers the process of its making, resulting in abstract forms that are matt, contorted, and bumpy. They are about the size of a human, their shape indefinable, still somehow like the limbs of living bodies holding on to or leaning on large, smooth glass discs.

These sculptures continue the visual language of The séances aren’t helping (2021), Bove’s project for the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, in which similar figures inhabited the otherwise empty niches originally carved into the museum’s façade with the intention of housing figurative sculptures. Bove’s project challenged the ubiquitous presentations of heroic sculptures in public buildings: her sculptures stood for something decidedly not epic, but abstract and suggestive.

At Zwirner, these sculptures no longer compete with spaces designed for work of a different order. Instead, they are in relationship with the space that creates the feeling of a single installation. The gallery, with its nineteenth-century glass-and-steel ceiling, was painted—walls, floors—a shade of gray similar to that of the stainless steel. The works have narrative titles—such as Vase Face III / The Skeleton Juggling a Baby in the Central Tableau of Heaven (all works 2022) and Vase Face I / The Ascent to Heaven on a Dentist’s Chair—but they don’t tell a single story; they remain elusive and multifaceted, open to multiple readings. All four take up the different sides of the room, and in the middle of the installation is a large, gray shape of a vase that almost reaches the ceiling.

In the second room, the walls are covered in soft pale mauve textile on which hang five smaller wall-mounted sculptures in fauvist shades of pink, yellow, and orange. Deluge of Literality is almost the same pinkish hue as the wall, a snaking meeting of two parts of stainless steel, set horizontally on top of each other, meeting halfway. What to make of their titles (in this room are also small sculptures called Discarded Antonym and Manx January, for example) which point to something outside the work, something beyond only its materiality? To my eyes, they hint at the convergence of disparate things in one time, space, movement, or fused by heat.

I look at the vase—it is a Rubin vase, that famous optical illusion that could be a vase or two faces directed at each other—and what I see (that is, think of) is Keats’s “Ode to a Grecian Urn” (1819), the one with “Beauty is truth, truth beauty.” In her book Keats’s Odes (2021), Anahid Nersessian ends her discussion of this poem with an anecdote the painter Benjamin Haydon recorded in his diary about looking at the Parthenon Marbles at the British Museum with Keats in 1820: “We overheard two common looking decent men say to each other, ‘How broken they are, a’ant they?’ ‘Yes,’ said the other, ‘but how like life.’”1 Those ancient, broken sculptures feel like ancestors to the fragile presence of Bove’s new works.

The presence of these sculptures feels human and full of life: in them I see a history of their making and a trace of their maker, not a disembodied thing. Keats, writes Nersessian, insisted that “what we love is sacred, as is the act of loving it.”2 Keats is writing about looking, Nersessian, in response, about the looker. But they’re both writing about bringing oneself into the encounter with the work, and arguing that it matters.

Anahid Nersessian, Keats’s Odes: A Lover’s Discourse (London: Verso, 2022), 56.

Ibid, 16.